A guide to the recorded music of Sly & The Family Stone. Enjoy!

Danny Stewart“A Long Time Away” (1961)

|

|

|

The Beau Brummels“Laugh, Laugh” / “Still in Love With You Baby” (1964)

|

|

Sly & The Family StoneA Whole New Thing (1967)A decent, if uneven, debut. This is what launched one of pop music’s brightest groups. Sly Stone was still working out the details of his musical vision, but tagging along is a fun ride. Even if they don’t quite fully achieve a “whole new thing” here, they at least established that they were gonna try. “Underdog” is a classic. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneDance to the Music (1968)The debut jumped around a bit trying to find precisely what Sly & The Family Stone were going to be about. Dance to the Music locked in to exactly everything that the “whole new thing” title of their debut promised. The songs are all catchy, upbeat, bright, and the lyrics deliver smart wordplay with some social commentary thrown on top. What might be difficult to appreciate in retrospect is that the group was interracial, and included both men and women, at a time when that was not happening elsewhere. They also had a horn section within the group, whereas most soul acts didn’t consider the horn section part of the group proper — like The Memphis Horns who played for just about every Stax Records singer. Most of the songs on Dance to the Music revolve around very similar material. But the group really proves their mettle by making each one sound fresh. Sly gave Miles Davis a copy, and Miles later had to ask for another because the first was worn out from so much use. While that might just seem like a mildly amusing anecdote, it does help explain an underlying strength of the album: the improvisational flair built around irresistible rhythms. |

|

The French Fries“Danse a la musique” / “Small Fries” (1968)

|

|

Sly & The Family StoneLife (1968)This is like a continuation of Dance to the Music. “M’Lady” is quite similar to “Dance to the Music,” for instance. But when you find a good thing, go with it. While not as essential as some of the group’s other albums, if you like their 1960s stuff this is worth seeking out. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneLive at the Fillmore East (2015)An archival live collection recorded shortly after the release of Life. This was initially released as a 2-LP limited edition album, then as an expanded 4-CD set. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneStand! (1969)Generally considered one of the group’s best albums. With “Everyday People” Sly reached the pinnacle of the unbridled optimism of the 1960s, in the process coining the phrase “different strokes for different folks.” The depth and feeling he fit into the space of a short pop song was a spectacular achievement. Stand! established the group as one of the most important pop acts of their time. This is not a bad place to start in their catalog. |

|

Sly & The Family Stone“Hot Fun in the Summertime” / “Fun” (1969)

|

|

Woodstock (1970)“Woodstock” has since become etched on social consciousness as a symbol of 1960s counterculture. Sly & The Family Stone were right there for it. The first album of material from the festival features a medley excerpted from the group’s performance. Additional recordings from Woodstock came out on Woodstock Diary, but it was not until 2009 that the full performance was available on an album. The original Woodstock album might help put the music in some kind of context though. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneThe Woodstock Experience (2009)

|

|

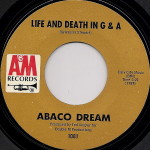

Abaco Dream“Life and Death in G & A” / “Cat Woman” (1969)The group released two throwaway singles (this and “Another Night of Love”) under the pseudonym “Abaco Dream”. “Life and Death in G&A” is a straight funk number, with the largely instrumental “Cat Woman” featuring lingering, psychedelic synthesizer — both oddities unlike anything in the proper Sly & The Family Stone discography. “Cat Woman” is the more intriguing side because it’s quite weird, for a major pop group or otherwise, while the A-side is driving but kind of simple. |

|

Sly & The Family Stone“Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” / “Everybody Is a Star” (1969)

|

|

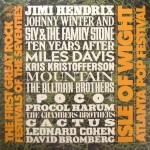

The First Great Rock Festivals of the Seventies: Isle of Wight / Atlanta Pop Festival (1971)

|

|

Little Sister“Somebody’s Watching You” / “Stanga” (1970)

|

|

Sly & The Family StoneThere’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971)The defining Sly & The Family Stone album is without question There’s a Riot Goin’ on. Whole books have been written about and around this album, so I will only sketch the key details. It represented an abrupt shift from the last album. Now dark, murky sounds dominated. Original band members were departing. Sly was using a drum machine, performing a lot of the music all by himself, and Bobby Womack appears somewhere in the mix. There really isn’t another album like this. Suffice it to say, it’s one of the all-time great rock/pop/soul albums. An absolute essential. |

|

Sly Stone“Rock Dirge” (1971) |

|

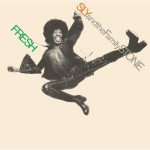

Sly & The Family StoneFresh (1973)Not nearly as militant and obtuse as There’s a Riot Goin’ on, Fresh had a crisper funk sound. It’s yet another classic. Few groups have ever produced a series of albums as good as Sly had from the late 1960s through (at least) Fresh. This is one of the essential Sly & The Family Stone discs. |

|

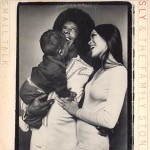

Sly & The Family StoneSmall Talk (1974)Sly took another turn with Small Talk. It had a much quieter, mellower sound than any of the group’s previous albums. The band was different, with a number of new members added and some old ones departed, and even boasted a violinist. This album really is neglected. The mature sound and lyrics dealing with raising a family and other domestic interests offer a new perspective on Sly’s music. Despite having a few weaker moments (like “Mother Beautiful” and “Wishful Thinkin'”), this has held up pretty well. People used to tell author Joseph Heller that his later books weren’t as good as Catch-22, to which he would respond, but what is? To say Small Talk isn’t as good as something like There’s a Riot Goin’ on, or even Fresh, is kind of unfair. No matter what, Sly had to go downhill at least a little as long as he kept releasing material following such magnificent previous achievements. As long as you don’t come to this looking for more of the same, it should be a rewarding listen. Small Talk deserves to be considered among the group’s better albums, even if it’s on a tier slightly below the all-time classics. |

|

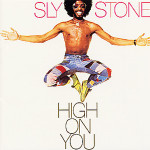

Sly StoneHigh on You (1975)High on You was not credited to “& The Family Stone”, which was perhaps a moot point with the original members of the band already disappearing in previous years. This is a respectable funk/soul outing, with a strong title track, though it’s nothing spectacular. The social consciousness that marked so much prior work was now gone and Sly was aiming only for a funky good time, though he generally succeeds in that more modest aim. Sly’s popularity would decline from this point forward. He was not really pushing himself anymore. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneHeard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back (1976)Perhaps due to the critical panning that Small Talk unfairly received, Sly’s next few albums tended to be merely attempts to recreate his “old” aura. Each one was billed as his big comeback. Heard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back is arguably the worst album in the catalog, though even Sly at his worst is at least adequate in the bigger picture. This one drifts into disco era fads at times, sports very bland horn arrangements, and the songwriting is completely forgettable. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneBack on the Right Track (1979)Another lackluster “comeback” album. It is an improvement over Heard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back as far as songwriting goes, particularly in the way this one reckons with changing times and Sly’s fading popularity. Worth it for “Remember Who You Are”, a real gem from Sly’s late period. But this is not the place to start. |

|

SlyTen Years Too Soon (1979)Well, for better or worse, this is one of the earliest remix albums. It’s a bunch of old Sly & The Family Stone hits recast for disco-era dancefloors. Profoundly unessential. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneAin’t But the One Way (1982)Sly all but disappeared for a while, though he briefly surfaced with Funkadelic for The Electric Spanking of War Babies. Then along came Ain’t but the One Way in 1982. In many ways, it marks the first time Sly actually presented a new sound since Small Talk. Unfortunately, the performances are generally lackluster. If the album could muster the intensity of “Underdog” in the horn section, things might have been different. Aficionados will probably want to seek this out, particularly for “L.O.V.I.N.U.” and “Sylvester,” but it’s not essential. |

|

Sly Stone“Eek-Ah-Bo Static Automatic” / “Love and Affection” (1986)

|

|

Sly StoneI’m Back! Family & Friends (2011)After a very long period of inactivity, and a few brief reappearances touring, Sly released his first album under his name in decades in 2011. What we have are mostly his old hits re-recorded, plus a few new songs. The old songs are all performed with guest artists. The hits are still great, and Sly has updated and modernized things in a way that needs no handicap. Yet, the guest spots add nothing and these re-recordings are somewhat redundant. Fans who love everything else may get a small kick out of this, but it’s nothing essential. It is worth mentioning that due to an ongoing dispute with his (former) manager involving allegations of fraud regarding his royalty payments, Sly was living in a van in a rougher part of Los Angeles since 2009. He indicated that he’s too paranoid to trust record companies to release any new material. |

|

Sly StoneRecorded in San Francisco: 1964-67Oddities collection. |

|

Sly StonePrecious Stone: In the Studio With Sly Stone 1963-1965 (1994)

|

|

Listen to the Voices: Sly Stone in the Studio 1965-70 (2010)

|

|

Sly & The Family StoneThe Essential Sly & The Family Stone (2003)

|