Country Music (2019)

PBS

Director: Ken Burns

Main Cast: Peter Coyote

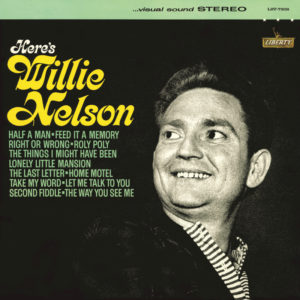

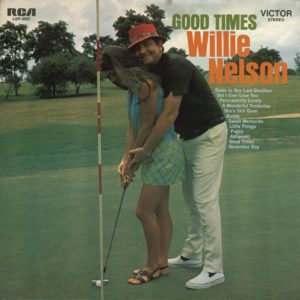

The episode that dealt with the mid-80s really starkly reveals the limitations of the series. You can really pinpoint that the acts featured in that episode (Ricky Skaggs, Randy Travis, Reba McEntire, George Strait, Roseanne Cash, etc.) constitute the tipping point when country music started to really suck. The episode repeats over and over the claim that these artists were returning to their “roots” (the episode is titled “Don’t Get Above Your Raisin’ “). But this proves to be false, or at least extremely misleading. Featured commentators do accurately state that in this period mainstream country acts moved away from the strings and backing singers that characterized earlier “countrypolitan” music. But the falsehood is that they did this to return to some mythical musical “roots”. Countrypolitan (or the “Nashville Sound”) was mostly about middlebrow, southern, white, working class-focused music appropriating the trappings of urban pop music of the 40s (like Frank Sinatra’s work with Axel Stordahl) to lend an air of sophistication to match rising post-WWII socioeconomic expectations that extended down the socioeconomic hierarchy in an unprecedented way. In a review of Willie Nelson‘s The Party’s Over (And Other Great Willie Nelson Songs) (1967) I previously wrote that countrypolitan music

“epitomized the (still racist and sexist) ‘golden age”’of post-WWII American prosperity in which ordinary, uneducated workers saw rising living standards and could see themselves as part of a newly emerging middle class with its own self-styled sophistication — something that might be described as attempting to project an aura of sophistication beyond class boundaries via ideas about ‘proper’ diction and enunciation cribbed from upper classes and merged with lower-class folk/country musical forms. Looked at another way, the temporary willingness of elite classes to permit rising working and middle classes was fostered by inculcating country music listeners with upper-class values as well as the speech patterns and more urban culture that went along with those values (when elites withdrew their permissive and benevolent attitude starting in the 1970s, the countrypolitan style faded almost in lockstep and is now commonly derided as low-class and unsophisticated).”

Johnny Cash’s The Baron (1981) is sort of a perfect example to illustrate the turn away from what countrypolitan music represented. Drawing on the work of Historian Jefferson Cowie about the sorts of socioeconomic changes that took place in the 1970s, as evidenced through music and film (Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class [2010]), I wrote that “given a close examination, there is is something to be admired in Cash’s intransigent support of his old New Deal style social optimism against the great weight of the Carter-Thatcher-Reagan era’s neoliberal onslaught against it.” Cowie has pointed to a dominant narrative of the lone individual failing or having a bittersweet ending trying to break away from the claustrophobic confines of social structures during the early neoliberal era, whereas on The Baron Cash took a kind of Spielbergian view of bringing a family back together, lamenting the loss of solidarity, family, community — that is, anomie.

When you actually listen to the music featured in the Burns episode about mid-80s acts, it is pretty apparent that what was happening was a modernizing effect as the most popular acts substituted sterile, highly compressed/gated, and synthetic 80s productions values from rock/pop music for the old countrypolitan strings and vocal choruses, and they were now utilizing a more highly affected country yodel/twang style of singing that had seemingly little precedent (it wasn’t at all a return to Jimmie Rodgers’ style of blue yodel singing). They were mostly just appropriating more recent rock/pop fads, with a few entirely new vocal affectations meant to distinguish it from the music of “urban elites” (now constructed as an enemy). And there is no explicit discussion of the (right-wing populist and reactionary and “Southern Strategy”) politics that go along with this. Though there were some photos/videos of acts posing with the Reagans and Ed Koch. What jumped to mind was Thomas Frank’s What’s the Matter With Kansas? (2004) thesis, and maybe Thomas Ferguson and Joel Rogers’s Right Turn (1987) thesis as well. Anyway, in the Burns series episode, what is not clearly explained is that the invocation of a return to “roots” is not a reference to musical qualities but is more a coded statement about constructing (through musical culture) an identity as a distinct social group opposed to certain (unstated) enemies. The way that the Burns series takes these statements at face value and refuses to unpack the coded implications is irksome (as Georg Lukács wrote in 1938, “It is an old truth of Marxism that every human activity should be judged according to the objective meaning in the total context, and not according to what the agent believes the importance of his activity to be.”). And, my my, most of the music in this episode is dreadful. When they showed some old Ricky Skaggs music video clips my spouse (appropriately) made vomiting sounds. Oh, and they talk to Roseanne Cash a lot through the series and in this episode she talks about her own career. My spouse was guffawing at everything she said because it was so transparently false. The series lets her get away with it (by airing the statements at all, as well as by omitting any critique of her statements). She claims she was not riding her father’s coattails but this is just completely contradicted by her actions (“I even thought about changing my name” … but she didn’t; she claimed to come to Nashville from LA, but she grew up in the south and had Nashville music business ties; etc.). As irksome as the episode is, some of the raw material in it at least allows a viewer to compare how earlier era country music was a more honest reflection of rural peasant/working class values (which is not to say all those values were admirable) whereas in the 80s it became more highly disingenuous and cynical and more prone to use coded language to obscure unappealing motivations. I guess an appraisal of mainstream country music in the 80s calls for an analysis out of Peter Sloterdijk’s Critique of Cynical Reason (1983).

The series does mention media consolidation in the 1990s. It is discussed for approximately 2 minutes (in a series with eight roughly 2-hour episodes!). Although some excellent points are raised in those two minutes, the problem is that they are given short shrift when the bulk of the series promotes winner-take-all frameworks, through incessant invocation of rags-to-riches motifs and an unrelenting focus on best-selling artists that presumes sales/profitability is the exclusive yardstick for merit. As part of those two minutes, the film makes a bizarre claim that the (Billboard?) “Americana” chart was created to capture alternative country in the face of media consolidation. The way it is discussed in the narrative conflates the “Americana” chart with “alt country” in a misleading way. They also briefly show a still photograph of the Dixie Chicks in a closing montage, but nothing after 1996 is discussed. Johnny Cash gets extensive time (yet again) in the final episode. It wouldn’t surprise me if 1-2 hours of the entire series is devoted to Johnny Cash (at the high end of that range if screen time by Roseanne Cash counts too). Hugely popular acts from the period like kd lang and Lyle Lovett are not mentioned at all. Garth Brooks gets a lot of time and much of the commentary by or about him is highly suspect (untenable assertions are taken at face value with no critique or contrasting perspective; my spouse once again guffawed when someone in the film says Garth Brooks refused to let his record label promote him outside the “country” market, as if a musician is willing and able to do that [whatever that really means anyway — does a highway billboard qualify as promotion outside the country market?]).

I guess in the end this makes me wonder if someone has written a good book-length treatment of country music from an interesting critical perspective–the sort of book that does not take self-serving statements at face value and that is willing to question industry motives and apply a kind of “objective” sociological or political science type of analysis (i.e., along the lines of Bourdieu’s Distinction).