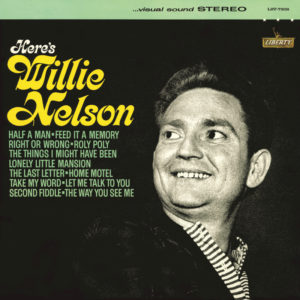

Willie Nelson – Here’s Willie Nelson Liberty LST-7308 (1963)

A common opinion is that Willie Nelson’s second full-length album Here’s Willie Nelson was a step back from his debut …And Then I Wrote. Those people often say that this is “Nashville cliché”, referring to the “countrypolitan” style it evinces. But a response to all that should be, “And?” Yes, Here’s Willie Nelson fits in the mold of the weepy drama of the “Nashville Sound” — a close comparison would be Skeeter Davis‘ “End of the World.” But it really represents the best possible execution of the Nashville Sound.

There are a couple of things that boost this album. First is producer Tommy Allsup. He was a touring member of The Crickets and once lost a coin flip to Ritchie Valens such that he lost a seat and was not on the plane that crashed near Clear Lake, Iowa on February 3, 1959 that killed Valens, Buddy Holly and The Big Bopper. Allsup brings out the best in the instrumental performances, accentuating the spark and energy of all the performers and balancing Willie’s vocals with the orchestration. He eschews the prominent focus on Nelson’s vocals evident on his debut. Surprisingly, pushing the vocals down a little in the mix works well.

Another key factor in the album’s success is the arranging work of Ernie Freeman and Jimmy Day. The orchestral treatments by Freeman are really quite excellent and much better than the formulaic leftovers that characterized Willie’s albums later in the decade for the RCA Victor label. Each song gets its own distinct character, matched to the tone of each song. Just check the calmly sizzling trills and glissandos from the strings on the bluesy closer “Home Motel,” and contrast the pastoral elegance and more complex harmonic blocking of “Half of Man” or the busy energy of the strings on “Take My Word,” or the juxtaposition of pedal steel guitar with sweeping string orchestration and indistinct backing vocal chorus of “Second Fiddle” where the orchestra briefly trades off with a solitary country fiddle solo and closes with a country/Euro-classical solo fiddle flourish. “The Way You See Me” displays masterful balancing of traded instrumental backing behind Willie’s insistent singing and a gently and slowly walking bass — alternating the more prominent voicing between fiddle, piano and pedal steel guitar in a way that reflects the song’s protagonist’s attempt to put up a dignified and happy facade to conceal his heartbroken loneliness. The vocal choruses combine both male and female voices, which adds a rich textural/timbral dimension. “Lonely Little Mansion” uses sustained vocal backing to add a kind of protestant church aesthetic of serene, austere, atmospherics, somewhat like what Johnny Cash used on songs like the B-side “Were You There (When They Crucified My Lord).” But then “The Last Letter” uses the vocal chorus’ expanding vibrato to emphasize a slight polyrhythm against the song’s core waltz rhythm. The orchestration is never overly complex or abstract. Yet there is still clearly much more effort put into it than on so many other Nashville sound recordings of the day.

After releasing his debut, Willie lamented that he wasted too many good songs on it. In other words, he felt the album was too good and should have been watered down! Unfortunately, that sort of thinking would prevail all too often over his long career. But it is also kind of a self-important statement, because it implies that his own songwriting was inherently better than that of cover songs he might record. Here’s Willie Nelson features a mix of original songs and covers. The covers are quite good though! There is absolutely nothing wrong with something like “Feed It a Memory” or a chestnut like “Roly Poly.” The stately elegance of a song like “Things I Might Have Been” captures the frustrated aspirations that perfectly fits the “countrypolitan” style. He may have choosen some covers rather than all originals here, but nothing is watered down.

Willie’s singing here is much looser and relaxed than on his recordings from later in the 1960s. He also tempers the “jazzy” affectations of his debut somewhat. Though those tendencies are still here. He still sings with a vibrato-less tone way behind the beat. On the opener, the western swing staple “Roly Poly,” he gets so far behind the beat that he barely finishes the verse he’s on before the band has moved on to another part of the song! In these various ways he finds a balance that suits the “countrypolitan” style better than on any of his other recordings in that style. His singing, honestly, isn’t always particularly great on the second side of the album. But it is never bad. But for the most part Willie singing on record became less welcoming for many years, until he passed through a sort of existential personal crisis in the early 1970s.

“Take My Word” is a weaker offering (but is also the shortest song here), as is “Let Me Talk to You,” with Willie limping along with jazzily dissonant phrasing. And, no, nothing here quite matches the heights of the best songs on the debut …And Then I Wrote. But this album still avoids the more jarring discontinuities between Willie’s singing and the studio band’s performances that appeared on his debut, and it manages to be more consistent on the whole. Frankly, Willie wouldn’t make a record this uniformly rewarding until 1971’s Yesterday’s Wine.