Link to a review by Sam Husseini:

Tag: Drama

Slavoj Žižek Quote About the Suffering of Others

Quote by Slavoj Žižek from “Margaret Atwood’s Work Illustrates Our Need to Enjoy Other People’s Pain”:

“In his Summa Theologica, philosopher Thomas Aquinas concludes that the blessed in the kingdom of heaven will see the punishments of the damned in order that their bliss be more delightful for them. Aquinas, of course, takes care to avoid the obscene implication that good souls in heaven can find pleasure in observing the terrible suffering of other souls, because good Christians should feel pity when they see suffering. So, will the blessed in heaven also feel pity for the torments of the damned? Aquinas’s answer is no: not because they directly enjoy seeing suffering, but because they enjoy the exercise of divine justice.

“But what if enjoying divine justice is the rationalisation, the moral cover-up, for sadistically enjoying the neighbour’s eternal suffering? What makes Aquinas’s formulation suspicious is the surplus enjoyment watching the pain of others secretly introduces: as if the simple pleasure of living in the bliss of heaven is not enough, and has to be supplemented by the enjoyment of being allowed to take a look at another’s suffering – only in this way, the blessed souls ‘may enjoy their beatitude more thoroughly’.

***

“In short, the sight of the other’s suffering is the obscure cause of desire which sustains our own happiness (bliss in heaven) – if we take it away, our bliss appears in all its sterile stupidity.”

Derek Nystrom – Thirteen Ways of Looking at “High Flying Bird”

Link to a review of High Flying Bird by Derek Nystrom:

Faces

Faces (1968)

Walter Reade Organization

Director: John Cassavetes

Main Cast: John Marley, Lynn Carlin, Gena Rowlands, Seymour Cassel

Johan Cassavetes’ Faces was his second independent production as a director. It is widely regarded as one of the most important American independent films. The film is a drama. Significantly, though, it is drama rather than melodrama. Theodor Adorno advanced a theory of the “Culture Industry”, which posited that standardized cultural goods — like formulaic Hollywood melodramas — encourage passivity and docility among the masses. It is immediately apparent that Faces is no mass produced, formulaic Hollywood melodrama! As one review succinctly put it, “Cassavetes’ gritty black and white drama analyzes the inevitable harshness of relationships (routine, jealousy, infidelity) through a rigid attention to complex emotions rarely seen in movies.” (Though one could question that review’s categorization of infidelity as “inevitable”).

The film centers around the marriage of Richard “Dickie” Forst (Marley) and Maria Forst (Carlin). Richard is an upper middle class corporate film executive — whose job seems to relate to financing in some way — entering late middle age, who has a posh suburban home, a predilection for boozing, and a womanizing “old boys club” male chauvinist attitude. The film opens with him at work, briefly, before he visits the home of a prostitute Jeannie Rapp (Rowlands) with his old friend Freddie (Fred Draper), where they carouse and make crudely cynical jokes. Maria Forst is introduced later in the film. She does not work, and the couple has no children. Her husband callously announces he wants to divorce after she refuses sex — with intended cruelty he immediately calls up the prostitute Jeannie in front of Maria. She goes out with friends to a nightclub and picks up a sort of hippie drifter Chet (Cassel). Much of the film consists of long, intense dialog-driven scenes that construct character portraits less through demonstrative action and sequential scenes that build on each other than through a series of emotive, confessional yet somewhat isolated dialogues (though of course there is more than just dialogue).

The film is often interpreted as an expression of dissatisfaction with the “American Dream”. And certainly there is something to that view. Faces draws a bit on the same sort of bohemian critique of bourgeois society as, say, Allen Ginsberg‘s beat poem Howl from a little more than a decade prior.

Richard and Maria each want something more than they seem to have, even as, materially, they have all the possessions they could want, and Richard at least commands corporate power and prestige at his job. In the film, though, the characters reach out to someone else, as if another person will provide a guarantee of meaning in their lives. And yet the film is somewhat cramped in its ambitions, in that the characters seem to at most jump from one misguided set of desires to another — if they really make any jumps at all.

The overarching narrative of individuals breaking free of social bounds and constraints that is reflected by the dissolution of the protagonists’ marriage in some ways anticipates the demise of the American New Deal coalition, which gave way to the so-called neoliberal era. Historian Jefferson Cowie‘s book Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class explored aspects of the phenomenon of individualism reflected in mass culture, drawing from the thesis of Christopher Lasch‘s famous book The Culture of Narcissism. Are the Forsts really striving for no more than hedonistic narcissism? As captured in Michelangelo Antonioni‘s splendid commercial flop Zabriskie Point, was this hedonistic narcissism also the basic problem in what the so-called “New Left” of the late 1960s aimed for?

The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has explained how the post-modern ethical injunction (of the superego) is to “enjoy!” The message that people in American society are constantly bombarded with is the command to enjoy themselves, and those same people are thereby induced to feel a loss if they do not experience enjoyment. Žižek elaborates that the role of psychoanalysis is “to open up a space in which you are allowed not to enjoy.” In this precise sense, the obstacle is to get rid of the injunction to enjoy rather than to merely shed inhibitions to more fully enjoy whatever consumptive, sexual, spiritual, or other activities people engage in.

The Forsts are kind of like heralds of the post-modern society. In being affluent, they aren’t barred from enjoying themselves by material lack, because they can afford any amusement or living arrangement they wish. In being white and having high social status, they also experience an almost complete social/legal permissiveness to do as they wish. So, they are in this sense able to be considered true post-modern subjects. When Richard Forst seeks a divorce, it is not that his character has any sort of awakening, really. Rather, it is that his character experiences guilt by his failure to enjoy his lifestyle of power and consumption. His impulsive demand for divorce is merely a way to double-down on his existing desires, and to try to remove what he sees (in the moment) as obstacles to those desires. He simply wants to consume more — and his recourse to a prostitute is a classic example of sex-as-commodity consumerism. Actually, the scenario in which Richard wishes to leave Maria (he seems to deem it an unserious request later in the film) is close to a classic one for psychoanalysts in which a married (chauvinist) man wishes to leave his wife for a mistress, only to then have his relationship with his mistress also fall apart because he misunderstood that his true desire to have a distant and obscure object (mistress as mistress) about whom to dream.

Maria’s situation is more complex than Richard’s. She lives a life at home, spending time talking with other affluent housewife friends. She resents her husband seeing her as merely there to serve (or service) him. When she goes out with her friends and brings home Chet, she is, in a sense, making her own choices, perhaps for the first time, and we might pardon the way those actions appear hedonistic at first glance. There is, though, a great scene with Chet at Maria’s house in which one of Maria’s older friends becomes indignant that Chet considers them dancing to be ridiculous, offended at the insinuation that she is too old for him. Then perhaps the oldest of Maria’s friends takes this further, trying to make herself the object of Chet’s desire by dancing with him then tentatively asking if he will kiss her, before she breaks down crying and asks him to drive her home. It is a moment of loneliness, the manifestation of social constraints of age and appearance, and an almost humiliating projection of desire. Chet soon returns to Maria’s for the night. This sort of undermines the aspect of Maria making her own choices — is the youthful Chet with her simply because she is the youngest of the women? She eventually attempts suicide, which emphasizes the difficulty in her conceiving a new way of life.

Jeannie and Chet are the characters with the most emotional honesty. Jeannie’s behavior, for her job, is self-evidently an act. The depiction of a prostitute as the most authentic individual in a capitalist society fits quite squarely with many French films of the era. Chet is a character without much depth, deployed often as merely a prompt for Maria’s character, but Cassel is wonderful in the otherwise flimsy role.

Although Faces is a groundbreaking film, it is also in some ways a less satisfying Cassavetes feature. The two main characters for the most part begin and end the film as unsympathetic fools. There are only dead ends and endless misery in their lives. Cassavetes’ later films explored in greater detail interpersonal dynamics without the hedonistic baggage that Faces carries. Those later films frequently explore with sympathy emotional bonds that are forged without regard for “happiness” as such. A possible explanation for this is a sort of “sour grapes” autobiographical one: Cassavates vindictively made a film about the shitty, miserable life of a film executive (and his wife) after he was run through the Hollywood meat grinder by such film executives when trying to work there as a director in the early 60s. And yet, such a view overlooks how this might have just been a coping mechanism for Cassavetes, whose real-life personal aspirations, and sometimes his behavior, bore resemblances to features of his Richard Forst character. So the ultimate limit of the film is that it gets caught in cynicism and ressentiment that hates what is all around it without quite taking responsibility for its own position within its society and how its desires are conceived as part of that very society. Though these limitations are minor in what is still an impressive cinematic achievement.

It would be good to pair a viewing of Faces with a self-consciously psychoanalytic film by Fellini or Jodorowsky like 8 1/2 or El Topo, or, perhaps more pointedly, Frankenheimer‘s Seconds, which metaphorically (and with a sci-fi twist) depicts the difficulty in trying to change one’s desire. Another good juxtaposition is Aldrich‘s The Big Knife, which is tied directly to the Hollywood film industry milieu albeit with more conventionally theatrical storytelling and presentation.

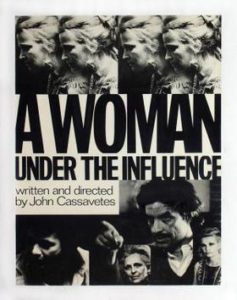

A Woman Under the Influence

A Woman Under the Influence (1974)

Faces International Films

Director: John Cassavetes

Main Cast: Peter Falk, Gena Rowlands

John Cassavetes’ wife Gena Rowlands asked him to write a play with an interesting female character for her to perform. That play ended up being unsuitable for live theatrical performance and was instead re-purposed as the film A Woman Under the Influence. Rowlands plays Mabel Longhetti, a stay-at-home mother of three children. Her mental disposition is one that is inconvenient to modern society (there being no objective definition of a “normal” mental state). Her husband Nick (Falk) is a working class construction worker. Nick is a rather angry and occasionally violent doofus who genuinely cares for Mabel. The film examines the reactions of ordinary people to Mabel’s unconventional behavior, and Nick’s attempts to cope with it — and to try to control it (and her). Mabel’s eccentricities eventually lead to her being committed to a mental hospital for six months — of note, Nick’s violent outbursts at home and work do not lead to him being committed or imprisoned. Nick proves inept but well-meaning as a sole parent during Mabel’s absence. The film concludes with an extended portrait of Mabel’s return home from the hospital. Nick planned a welcome home party, though the presence of a crowd is questioned by his mother (Katherine Cassavetes) as being too stressful for Mabel. As the guests eventually are thrown out by Nick’s mother and then Nick, Mabel clumsily attempts suicide, and her children become distraught. In a fitting conclusion echoing the ancient myth of Sisyphus, Nick carries his children upstairs to their bedroom only to have them run back downstairs to their mother and the process repeats. Such a “punishment” is fitting for Nick, as a self-aggrandizing jerk whose children seem more genuinely connected to their mother as a person with her own free will than he does.

A Woman Under the Influence is one of the “mature” Cassavetes films, in which his style that blends intense scripted and improvised acting expands upon what he had done in earlier films like Faces and Husbands, notably improving upon the overall pacing, while also deploying a much less conventional narrative structure than Minnie and Moskowitz. Rowlands and Falk give tremendous performances. Cassavetes’ narrative examines the characters’ personal situations from a sympathetic perspective, with his iconoclastic film techniques offering a much deeper palette of complex emotions than is typical in movies. What sets A Woman Under the Influence apart from Faces is that, here, a couple is struggling to keep their family together, whereas Faces saw characters striving to break free of social constraints (while ironically and cynically doing so to seek social validation). The two main characters are each unusual for feature length films, in that middle aged, working class protagonists are usually portrayed only at the margins of Hollywood cinema and the industrial nature of film production prices out most would-be independent ventures that might otherwise show interest.

These characters are all flawed, but worthy of human dignity nonetheless. Nick’s struggle to control the people and situations around him — and his frequent inability to do so — is his most pronounced character flaw. Mabel is less a “flawed” character as much as one with a combination of inability and unwillingness to conform to social expectations. Cassavetes’ movies often featured a free-spirit “hippie” character (often played by Seymour Cassel). The Mabel character is sort of a twist on that theme. This prompts frequently draconian reactions. Mabel’s commitment might be compared to the real-life story of the feminist scholar Kate Millett. This is the “hysterical woman” motif:

“Remember what hysteria is? To simplify it, from a psychoanalytic standpoint, society confers on you a certain identity. You are a teacher, professor, woman, mother, feminist, whatever. The basic hysterical gesture is to raise a question and doubt your identity. ‘You’re saying I’m this, but why am I this? What makes me this?’ Feminism begins with this hysterical question. Male patriarchal ideology constrains women to a certain position and identity, and you begin to ask, ‘But am I really that?’ Or to use the old Juliet question from Romeo and Juliet, ‘Am I that name?’ Like, ‘Why am I that?’ So hysteria is this basic doubting of your identity.”

The sympathy that Cassavetes shows his flawed characters is unique. Unlike, say, Pier Paolo Passolini‘s underclass protagonists, like the titular character in Accatone, Cassavetes’s films often deal with characters situated away from class conflicts. The Longhetti family is working class, but we see them with a comfortable home and steadily employed without obvious want. This allows for a unique focus on the characters’ inner psychology, in which viewers can witness the characters questioning their own actions and pursuing changes in their lives while at the same time struggling to make the right changes and repeatedly failing to actually change their desires as reflected in their actions. While certainly many other filmmakers relied on psychology to inform their work, Cassavetes was unique in the raw, harsh and almost bleak realism with which he depicted these things. His films are largely free of simplistic symbolism. Surprisingly, it is an approach that shared some similarities with some films of the Socialist Realism genre, such as Béla Tarr‘s early short Hotel Magnezit, albeit with the freedom to explore subjects other than a critique of bureaucracy.

In the end, A Woman Under the Influence remains a “difficult” film filled with enough heart to remain engaging from beginning to end. This is another landmark of American cinema from one of its greatest writer/directors.

Poesía sin fin [Endless Poetry]

Poesía sin fin [Endless Poetry] (2016)

Satori Films

Director: Alejandro Jodorowsky

Main Cast: Adan Jodorowsky, Pamela Flores, Brontis Jodorowsky

This is the best new(-ish) film I can remember seeing, a fact bolstered by watching the horrendous Star Wars: The Last Jedi at a second-run theater shortly after it. This autobiographical work draws from the second part of The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography (2001), and chronologically follows Alejandro Jodorowsky’s previous film La danza de la realidad [The Dance of Reality] (2013), which also drew from his autobiography. This is not a conventional, “accurate” or “realistic” autobiographical picture. Some scenes are altered from their historical sources, and most of the film represents stylized exaggerations of real-life events for artistic effect. While this can definitely be called Felliniesque — Amarcord, Satyricon and 8 1/2 being perhaps the closest counterparts — everything here is unique to Jodo and nothing can really be said to be copied from Fellini or anyone else. Jodo’s predilection for combining psychoanalysis and shamanism completely and irrevocably marks his own style. But perhaps it suffices to say this is about as good as Fellini at his best.

The film opens with Jodorowsky in his teens, still living in Tocopilla, Chile. Jeremias Herskovits reprises his role as the young Jodo. But his family relocates to Santiago. He develops a love of poetry. Eventually he runs away from home and is taken in by kindred spirits at a kind of artist commune. There he works on his poetry and begins making puppets for a puppet show he presents with a friend. He cultivates relationships with local poets and spends time in bars recreated here with surreal decor. He then is given a loft apartment, by chance, where he comes into himself as a young adult. A particularly moving scene is the very end of the film. This is where Jodorowsky decides to leave Chile for France. His father meets him at the port as he is leaving. In real life, he never saw his father or other family members again. But here, as a kind of narrator, he steps in to ask his younger self to forgive his father and insist on a different interaction with the father character. The film is historical, but also a dialog with the director’s own past, as a kind of quest to confront and overcome his own mistakes. Numerous scenes depart from the way Jodo described them in his earlier book The Dance of Reality. While sometimes that means the filmic depiction is exaggerated, in some instances things are toned down to be more presentable on screen.

One recurring effect is the presence of stage hands dressed entirely in black, including gloves and full-head hoods. These stage hands take things from the actors’ hands and hand them other things. Familiar in theater productions, here the effect is to consciously direct the audience to the symbolic significance of characters’ actions on screen and to heighten emphasis on the characters’ emotional states. Another device used repeatedly is the active unveiling and movement of life-size black-and-white posters of buildings and a train. These convey the past in a kind of distant echo, real yet unreal. They allude to the past while recognizing that events can’t be fully re-created, only conjured up from vague memories from a new perspective. Then the end of the film features a crowd, half dressed in skeleton costumes and half dressed in red devil costumes. The skeletons appear elsewhere in the film too. These images are striking and indelible.

Jodorowsky’s wife Pascale Montandon-Jodorowsky provides lighting, color and costume contributions. All of these aspects are particularly striking and effective. His son Aden plays his teenage self, and his oldest son Brontis reprises his role as his father. Pamaela Flores reprises her role as his mother, again singing all her lines in an operatic style, but she also portrays the poet Stella Díaz Varín, Jodo’s first girlfriend.

This is a somewhat smaller-budget film. Moviemaking is an industrial art, demanding substantial funds. It is simply not possible to realize certain things without money. Jodorowsky is quite open about his outsider status as a filmmaker, and his acceptance that his quest to make art for art’s sake places him squarely in opposition to the profit-focused Hollywood machine. He ran out of funds mid-way through filming Endless Poetry, and raised the remaining funds through a “crowdfunding” campaign. While there is the potential to see his efforts as self-aggrandizing, taking Jodo’s mysticism — drawn from zen buddhism, the tarot, and elsewhere — at face value, he doesn’t hesitate to work on his own personal “inner” growth, or to use himself as an example — good or bad — for others. This attests to some sort of more noble purpose. Returning to the Last Jedi comparison, this film presents a much more worthwhile exploration of a master/apprentice framework, particularly in the way Jodo appears directly as a kind of narrator. The Last Jedi is sub-moronic in that respect, when you get down its anti-zen “striving” narrative. These elements become even more pronounced in later parts of Jodo’s real life.

Jodo is still only part way through film adaptations of the book The Dance of Reality, and that isn’t even counting his other memoirs about episodes of his adult life like The Spiritual Journey of Alejandro Jodorowsky. Supposedly he plans a five film cycle, of which this is the second. Though it does seem that the third installment is underway in some form.

Being more about Jodo’s inner struggles to “become himself” when he a teenager, rather than being about his father, makes this just a bit more interesting than its predecessor The Dance of Reality. The visuals are also more extravagant and memorable here. This is why movies are made!

To the Wonder

To the Wonder (2012)

Magnolia Pictures

Director: Terrence Malick

Main Cast: Olga Kurylenko, Ben Affleck, Javier Bardem

In a way, this film is perhaps the most abstract possible art house take on a typical daytime soap opera, and also the most beautifully photographed. Terrence Malick continues to structure his films through the fragmented flashback approach of The Tree of Life. Though here he takes up the challenge of applying his penchant for beautiful images to a setting of dingy exurban American neighborhoods, with their imposing power line towers, rivers contaminated with toxic waste, and nearby landfills. But To the Wonder is as much pastiche and tribute as anything. There are the metonymns of Michelangelo Antonioni, especially in the American exurban southern plains settings with their bleak declining economic prospects — some of these bits of the plot resemble the contemporaneous The Promised Land — which parallel the relationship of the protagonists. There is also ample reference to late-period Godard — the long shots of sunsets and water, a bit like Helas pour moi, the “mature” and “boring” relationship focus of Sauve qui peut (la vie) and Goodbye to Language (which actually came out later), or even his 1971 TV commercial for aftershave. Following Robert Bresson, the performers in the film are more like “models” than “actors”. Neil (Affleck) barely says a word the entire film, which is fine. In fact, aside from disembodied voice-overs (mostly in French), there is almost no dialog between on-screen characters at all.

This film, if nothing else, is about emotion and desire. The characters struggle to control and take responsibility for their own desires. What do they want their lives to mean? While it is tempting to look at Marina’s (Kurylenko’s) catholic faith as an affirmation of accepting religion to guide her, Malick does problematize her religious faith somewhat. Her prior marriage is held against her by the church. She perhaps wants the church to guarantee meaning in her life. She seems to give up that futile hope somewhere along the way. The Father Quintana (Bardem) character, though pasted onto the main story a bit, is key. The presentation is indelicate, with its parade of downtrodden figures presented near the conclusion of the film, but when Quintana goes around to help the poor and marginalized, he simply does it without any recognition or even any sorrow. And this character (who perhaps speaks as much or more than any other in the film, aside from the voice-overs) always helps others and asks them to persevere in working with each other. He often does these things to a congregation of just a few people, the pews mostly empty. One of his parishioners tells him she prays for him to have joy, because he seems to have none. But his perspective, a rather unfashionable one, seems to connect with the two main characters by the end of the film. They at least pause to reconsider their visions of romantic relationships, and commit to work at them.

The perspective Malick seems to put forward might be explained with reference to G.K. Chesterton‘s “Introduction to the Book of Job,” about the old testament biblical character of Job.

“God will make Job see a startling universe if He can only do it by making Job see an idiotic universe. To startle man God becomes for an instant a blasphemer; one might almost say that God becomes for an instant an atheist. He unrolls before Job a long panorama of created things, the horse, the eagle, the raven, the wild ass, the peacock, the ostrich, the crocodile. He so describes each of them that it sounds like a monster walking in the sun. The whole is a sort of psalm or rhapsody of the sense of wonder. The maker of all things is astonished at the things He has Himself made. This we may call the third point. Job puts forward a note of interrogation; God answers with a note of exclamation. Instead of proving to Job that it is an explicable world, He insists that it is a much stranger world than Job ever thought it was. *** Here in this Book the question is really asked whether God invariably punishes vice with terrestrial punishment and rewards virtue with terrestrial prosperity. If the Jews had answered that question wrongly they might have lost all their after influence in human history. They might have sunk even down to the level of modern well educated society. For when once people have begun to believe that prosperity is the reward of virtue their next calamity is obvious. If prosperity is regarded as the reward of virtue it will be regarded as the symptom of virtue. Men will leave off the heavy task of making good men successful. They will adopt the easier task of making out successful men good. *** The Book of Job is chiefly remarkable . . . for the fact that it does not end in a way that is conventionally satisfactory. Job is not told that his misfortunes were due to his sins or a part of any plan for his improvement.”

The way Chesterton interprets to story of Job is to say that when Job demands an explanation from god about why he suffered so, god responds with a “that’s such a ‘first world’ problem” sort of answer! It isn’t that god operates on a level beyond human understanding, which is the more conventional interpretation of the story, or even that suffering is ennobling through some connection to sin or a plan for improvement. Job’s suffering and misfortune is insignificant in a universe full of such things. Nature is simply full of misery. And so it is with Neil and Marina. Yes their relationship is fraught, but of what importance is their failure to hold together a stupid, happy nuclear family in the face of a universe of (much greater) suffering?

This point is underscored, in a different way, in a scene in which Marina’s friend walks through a neighborhood with her, and suggests she make a calculated bid for her own happiness, just the way Chesterton suggests that god’s explanation of the creation of the universe is blasphemous, a kind of calculated wager in which god performs all sorts of selfish acts in preparation for his own battle of armageddon without much concern for the suffering inflicted along the way. Marina ultimately doesn’t accept that sort of narcissism, though she toys with it briefly.

There is an amazing unfinished novella by Andrey Platonov titled Happy Moscow, in which a parachutist — a glamorous occupation in its 1920s Soviet Union setting — named Moscow Chestnova goes to work building a subway and is maimed, then goes to live with a derelict and helps him get on with his bleak life. The story is so compelling because of its arc away from personal achievement and recognition. Chestnova accepts the lowest possible social position and helps others as a kind of gray duty. She finds nothing unhappy in a landscape usually considered dystopian. This is what “happy” Moscow looks like! The tenor of Platonov’s story recalls a little bit the Lao Tzu saying that a good person is like water, always going to the lowest places where no one wishes to be, benefiting everyone and harming no one, without striving. This humble, unglamorous sense of duty is lurking behind many of the scenes in the film.

The melodramatic story of To the Wonder repeats age-old wisdom, suggesting that ascending steps “to the wonder” and the rush of “new romantic love” need to give way to hard work at relationships, and on one’s own desires and subjective reactions to objective circumstance. But the film addresses all this on the level of emotion and feeling. It might be fair to call it “trite”, but only when looking at the premise from a cerebral and intellectual position, which is what this film challenges the viewer to reject. I think this is most true of the semi-urban modern landscapes. Can the viewer choose to find the beauty in those images and be awed by that beauty? Can the viewer find a sense of wonder and awe in “trite”, common human situations?

At a deeper level, the film suggests that the main couple’s original desire was built around just the simple pleasures of their tryst and its playful, romantic games so characteristic of “new love”, and any long-term relationship was really perceived as some bonus or unexpected surplus, a kind of insatiable gap of unconscious social expectations never satisfied or bridged by the simple pleasures. Even the couple’s other affairs that happen later suggest a conscious pursuit of simple sensual pleasures and no more, yet a fundamental void remained unfulfilled by those pleasures because they hadn’t grasped that they were bound to further social expectations. This is what the film questions. By the end, the main characters have started to probe and understand their desires, and they decide for themselves to build relationships (though it is ambiguous if that means staying together, or seeking other partners, given the film’s non-linear chronology), accepting simple pleasures along the way for what they are. The broken flashback approach strengthens this conclusion, by suggesting the memories of simple pleasures remain, re-contextualized in the face of new desires that really go beyond what they were originally. So, the ultimate choice is one different from imposed social expectations, to instead fashion lives/relationships on the couple’s own terms, but making that choice consciously and without the traumatic, insatiable emptiness of having to constantly convince themselves that they want to accede to social pressures to have a “stable nuclear family” required making the “wrong” choice first. Like Moscow Chestnova in Happy Moscow, they ultimately opt for a kind of dingy view of relationships, stripped of the glamour of some idealized and unobtainable social conception of the perfect marriage, but with a sense of mutual duty and recognition of what are not fundamental needs, and no demand for martyr status or vindication for past suffering. (For what it’s worth, episodes in season three of the cartoon TV show Rick and Morty dealing with the character Beth focus on similar issues). Maybe the ambiguity of the film’s ending suggests that the main characters see relationships as only fleeting, grasped when they can be and relinquished when the cannot hold. Thankfully, there is no didactic characterization in the film.

Unlike Malick’s early films, which tended to take aim at shibboleths of modern society in ways that had parallels in the counter-culture and high art, To the Wonder is rather more daring in its use of “lowbrow” melodrama, juxtaposed against high-concept cinematography of the type that appeals primarily to viewers who normally look down upon melodrama. This may be one of Malick’s least regarded late-period films. But it has things to offer, even if, no, it isn’t up to his first three features — though few films are. Most detractors seem to focus on the characters being thin, undeveloped or uncompelling, or something like that, but those criticisms seem to miss the point in that they are meant to be shells without their own positive desires, which they try (and at least initially fail) to construct.

Jim Thorpe -All American

Jim Thorpe -All American (1951)

Warner Bros.

Director: Michael Curtiz

Main Cast: Burt Lancaster, Charles Bickford, Jim Thorpe

On the one hand, this film admirably portrays the life of a native american. On the other hand, it is highly problematic. There are some decent acting performances, but the score is tedious Hollywood pap. The script is the biggest problem. First of all, it is not very historically accurate, sacrificing facts to develop melodramatic plot points. But the worst thing about it is that the story is designed to emphasize personal failings to diminish the nagging problem of racism. Now, the film does address racism. But it is brought up mainly as a “strawman” to be knocked down in favor of a formulaic personal struggle narrative arc. It presents Thorpe’s life as one of him being too emotionally weak to succeed (in the face of racism, personal tragedies). To draw an analogy, this is premised on the Louis Armstrong or Sammy Davis, Jr. model — a great individual can overcome all institutional and social obstacles (racism) just by being personally talented enough in ways that are non-threatening to social power structures. This is essentially a parallel of the “Talented Tenth” theory of W.E.B. Du Bois (later disavowed) and the questionable advocacy of Booker T. Washington. In other words, without any irony, Thorpe is merely expected to have a superhuman willpower and resolve to overcome discrimination. The real-life Jim Thorpe was subject to a level of discrimination well beyond anything depicted in the film, and the film would have been much better if it addressed that (and had a better score). For that matter, one would hardly realize from the film that its timeline runs through the Great Depression. Anyway, fortunately in the coming years there were other, sounder ways of looking at these sorts of questions gaining traction (see Frantz Fanon, Paulo Freire, etc.).

Arrival

Arrival (2016)

Paramount Pictures

Director: Denis Villeneuve

Main Cast: Amy Adams, Jeremy Renner, Forest Whitaker

This sci-fi film has roughly the feel of Contact (1997), with a bit of The Tree of Life (2011) thrown in for good measure. Credit goes to the many members of the crew who make this a marvel of technical skill. But the script falls apart in confusion as the film goes on. The central story line involves the arrival of extra-terrestrials to Earth, and the attempts of humans to communicate with the aliens. The protagonist is Dr. Louise Banks (Adams), a linguist brought in by the U.S. military. A central plot point involves invocation of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, a real-life theory that is stretched to absurd lengths in the film. This is precisely where the film fails. Rather than the grand tradition of using sci-fi scenarios to open space to discuss wholly realistic human social concerns otherwise barred from “respectable” discourse, Arrival reverts to empty deployment of “magical” actions. Actually, from the beginning to roughly the middle of the film, it seems almost that it will be about something that was in Stanisław Lem’s classic sci-fi novel Solaris that was excised from every film version — that humans are unable to comprehend “otherness” (explicitly that of aliens, but implicitly of other humans). But that would seem to be beyond what Hollywood permits, so by the end the plot gets dumbed down to pointless time-travel drivel.

I, Daniel Blake

I, Daniel Blake (2016)

Canal+

Director: Ken Loach

Main Cast: Dave Johns, Hayley Squires

One of the best “straight narrative” films I’ve seen in a while — reminiscent in some ways of Mathieu Kassovitz‘s La Haine [Hate] (1995). Basically, the premise of the film comes from Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward‘s theory about social welfare programs being about politically “regulating the poor” rather than solving the problems that create poverty. (It is a modern twist on something that people have written about for a long time). In that respect, the film is meant to convey how the politicians who intentionally — though never explicitly, that is, they never openly admit as much — seek to implement policies that are ultimately cruel to the poor and trap them in extreme poverty have “blood on their hands”. At the extreme end of that spectrum, historically, would be the imperialist British policies in India during the late Victorian era, in which British support for native Indians was at levels less than what the Nazis gave to concentration camp prisoners during WWII (!). While the film’s narrative is pared back from all the complexities of the real world, notably racial animosities used to prevent the kinds of solidarity repeatedly shown in the film, there is nothing far-fetched in the story. The concision is understandable for a film meant to be accessible.

The most blunt premise of the film is unabashedly political: “Does the masses’ struggle for emancipation pose a threat to civilization as such, since civilization can thrive only in a hierarchical social order? Or is it that the ruling class is a parasite threatening to drag society into self-destruction, so that the only alternative to socialism is barbarism?” Slavoj Žižek, Afterword to Revolution at the Gates: Selected Writings of Lenin From 1917 (p. 210). This film argues the latter. And the way it does so is to magnificently depict the so-called “banality of evil”, the way the Kafkaesque bureaucracy mostly turns a blind eye to the callousness of its action in exchange for a (semi) privileged position above those who bear the burdens. It also bears mentioning that I, Daniel Blake makes very modest demands. For instance, the film goes to great lengths to depict the protagonist as someone who has skills (he is a carpenter) who simply can’t work because of a health condition (he recently had a major heart attack), as opposed to defending, say, someone who has no skills but still deserves to be treated with dignity. In other words, the film goes out of its way to make clear it is not endorsing the notion of “to each according to her needs, from each according to her abilities.” It might well have.

A few words for non-British viewers are in order. The plot involves the protagonist seeking social welfare benefits after his doctor says his recent heart attack means that he cannot safely work. In England, there is a national health service (i.e., socialized medicine), meaning that the (unseen) doctor who gives that diagnosis is a government doctor. The welfare officials who deny him benefits constitute a vying faction of the government. What isn’t made explicit in the film is that the Tory (conservative) government of David Cameron had gone to great lengths around the time of the film to purposefully undermine social welfare benefits, for ideological reasons. Those sorts of cruel efforts continued in various arenas under the Theresa May government.

![Poesía sin fin [Endless Poetry]](http://rocksalted.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Endless_Poetry.jpg)