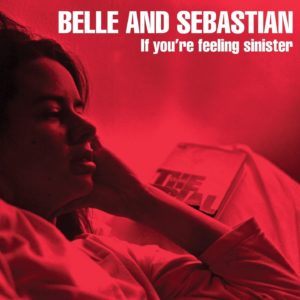

Belle and Sebastian – If You’re Feeling Sinister Jeepster JPRCD001 (1996)

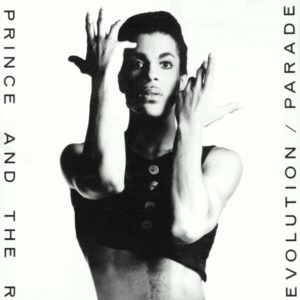

If You’re Feeling Sinister is one of the best expressions of the vacuity of the post-political late 1990s, after the so-called “end of history”. In the UK, the rising “third way” new labour politicians like Tony Blair (and the Democratic Leadership Council new democrat Bill Clinton in the United States) concealed a rightward shift behind benign-sounding “triangulation”-type rhetoric. Rather than a pendulum swinging back leftward after the brutal Carter-Thatcher-Reagan-Major era, there was an impotent shrug of “there is no alternative” (TINA) and a continuation of the swing rightward. So somebody like the girl in the album’s austere cover photo, with a copy of Kafka‘s The Trial conspicuously visible in the background, is left isolated and powerless, in contemplation. The sort of education and erudition implied by the book in the background of the album cover was no substitute for the lack of political power of the album’s core “college rock” audiences (the would-be new “new left” of the day). This feeling is captured well by Belle and Sebastian’s light, melodic, and sometimes whimsical chamber pop music. Stuart Murdoch sings with sensitivity but above all a wispy, unobtrusive breathiness. The music relies on a tension between the upbeat, nearly campy melodies and the literate, melancholic lyricism. This music is the soundtrack to the strongest revolution possible without getting out of bed.

Mostly the album uses folky acoustic instrumentation layered and elaborated upon with studio overdubs and subtle echo that draws from modern pop. That is to say from The Velvet Underground (in the vein of “Sunday Morning,” etc.), to British folk-rock of the 1970s to jangle pop of the 1980s and on to shoegaze rock of the 1990s all contribute influence. (Alt/grunge rock and britpop of the early-to-mid 90s is conspicuously absent). It all contributes to a kind of soft yet connected sonic fabric buoyed by odd drum figures, solitary horn accompaniment, unexpected electric bass lines, and celeste-like keyboards. It all seems fit together. The little subtle touches of eccentric instrumentation — never overused — each cycle through to diversify the proceedings, as if any instrument is capable of filling any role.

Some of the songs are simply lovely and pretty, like the piano ballad “Fox in the Snow” (a re-write of “We Rule the School”). The lonely tranquility and search for escape through fey artistic pursuit recalls Denton Welch‘s unfinished autobiographical novel A Voice Through a Cloud. Just like that book, there is quality of observing surrounding life, as if through a telescope.

“Stars of Track and Field” evidences a deadpan sarcasm — worthy of a Naked Gun film — that surfaces repeatedly throughout the rest of the album. The sarcasms allows the angst underlying the songs to come through in a passive-aggressive way.

“Get Me Away From Here I’m Dying” is probably the centerpiece of the album. The subtle appeal to rescue from unseen outside forces, the casual and polite cynicism, the somewhat smug obscurantism, the passive-aggressive hesitation to make offense: these are all the tools in the kit of “outsider” hipsters of the era. These are much the same techniques found in other indie “twee” pop like Neutral Milk Hotel‘s cult favorite In the Aeroplane Over the Sea from a few years later. And yet, Belle and Sebastian do something subtly different from Neutral Milk Hotel. “Get Me Away From Here I’m Dying” has the lines, “Nobody writes them like they used to / so it may as well be me.” This may be music that self-consciously (and even melodramatically) emphasizes its distance from the “real world” by building up its own private one, but at the same time it underscores doing something, however inchoate, apart from (and often against) those other worlds. So, rather than just being song about a “Romantic tragic hero, narcissistically focused on his own suffering and despair, elevating them to a source of pleasure,” these are songs that establish a larger context of political paralysis and meager responses. There is an emphasis on retaining sensitivity (the lyric: “I always cry at endings”), but also an emphasis on combining that with persistent awareness and action. Available avenues for action were limited at the time, and so naturally this music looks back to the past a bit, and appears quite tentative. While combining reverent/irreverent mash-ups of ironic camp and cutting insights is kind of an old tactic (at the time, most popularly employed by Beck), Belle and Sebastian’s use of the technique was so light as to almost pass by unnoticed. The cynicism almost gets the best of the band sometimes, with their tendency to play “the jaded, hysterical sniveller” holding them back rather than moving them forward as intended — this is evident by the way later work like The Life Pursuit is able to be more decisive and less self-pitying. This all boils down to the band firmly encouraging and arousing a constituency (audience) to recognize its peculiar strengths, but beyond that taking only the smallest of steps here towards deploying those strengths as a political force. The smallness of the steps is measured against what seemed possible.

If You’re Feeling Sinister is an album full of good intentions. It even manages to win over some listeners not usually into this sort of thing.