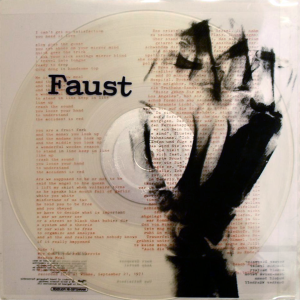

Faust – Faust Polydor 2310 142 (1971)

Goethe‘s Faust tells a myth that originated with the life of Simon Magus, a Gnostic who died in Rome while attempting to fly — at least one account indicating he “flew” with an intention to destroy his own body. The German rockers Faust had an approach not so very different from Simon Magus. Faust were more than willing to break from all the commercially viable music of the day. Screw the usual consequences. Isolating themselves in a converted schoolhouse in Wümme, the group recorded the album in three days to satisfy their record label. In doing so, Faust moved towards something confounding by conventional standards, but they did so with an offhand charm that is very special. Mechanized rhythms appear, then melt away. Melody is faint. They include snippets of other music (like The Beatles’ “All You Need Is Love” and The Rolling Stones‘ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction”), with the opening segment of “Why Don’t You Eat Carrots” sounding like tuning in a radio to different channels (like Kurzwellen, Hymnen, “Program” from Silver Apples, or “Radio Play” from Unfinished Music No. 2: Life With the Lions) amid waves of static. The music unfolds at a lethargic pace. This stands in contrast to the industrial sounds the band makes. Industrial society is usually about efficiency, and that tends to mean speed and precision. That is sort of the crux of this (anti-)music: it has a contrarian way of turning music of an industrial age into almost pastoral collection of vague non sequiturs. The album self-consciously tries to be different (perhaps The Residents‘ Meet the Residents is a rare attempt to follow-up on this style of music). Faust’s later work is better, but this debut still stands as a defiant remnant of the tail end of the psychedelic era, when it seemed like the world could be reshaped in new and unexpected ways. If lots of the hippie stuff of the late 1960s got co-opted, Faust is one album that resists assimilation more than most. The packaging of this album also bears mention for its uniqueness: a clear vinyl record in a transparent sleeve showing a x-ray of a clenched fist (the word “faust” means “fist” in German), with a transparent lyric sheet. It captures well the spirit of the music it contains.