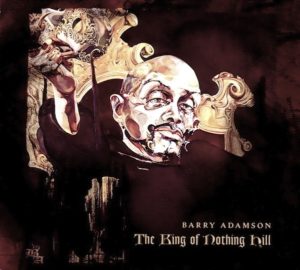

Barry Adamson – The King of Nothing Hill Mute CDSTUMM176 (2002)

Barry Adamson, the maestro of fake soundtrack music, has a firm conviction to the devilishly absurd. His ridiculousness is part of his appeal. He is a collector, suggestor, director and actor. The illusory story lines hinted at on his albums can pull emotions and moods out of practically nothing. He takes the listener places. Plenty of new experiences are waiting. The King of Nothing Hill fits a sleek action thriller, the sorts with spies, international intrigue — that sort of thing. While it sounds like an exotic, action-packed journey, it is still pop music. It is just on the fringes. That seems like a comfortable home for Adamson.

“The Second Stain” and “Twisted Smile” pulse with monotonous vamps until the mood envelops everything. The songs point, prod, and push. Bass and keys alone can rush listeners back and forth between the highs and lows. Adamson can pick you up and place you carefully in new surroundings, ready to experience the moments as they arrive. You have to be open to the possibilities, true. If you’re not willing to budge then Adamson’s efforts might be an annoyance. He does have a talent for always being inviting though. You have to be quite closed-minded not to be swayed a little.

A funky workout session takes place on “Cinematic Soul” (cribbing a bass line from “Sing a Simple Song”). Adamson can be as brash and glitzy as anyone and still pull it off. His material may be described as rather composed, but it can boogie too. Then more surprises come when “That Fool Was Me” has the sultry soul comedy of him singing, “only a fool would leave you / and that fool was me.”

The King of Nothing Hill makes considerable use of electronics and sound effect samples. There is sometimes an erratic pursuit of a number of different styles, but Adamson uses those shifts to convey a sense of changing scenes in a movie. The effect can be a bit demanding over the course of the rather lengthy runtime of the album though.

As Above So Below, the predecessor album, had more lounge jazz/acid jazz and bleak, blaring trip-hop pushing it ahead even if it subdued the pseudo-soundtrack impressionism. Both efforts toy with kitsch. All things said, the albums are about equally good, just in different ways — if anything this album has more cohesive and focused individual songs even as it lacks some of the elusive intrigue overall.

The King of Nothing Hill is refreshing. Almost a decade and a half after its release, it has to be given credit for capturing the feel of the sorts of action thriller films it evokes. Granted, the lyrics go beyond what pure soundtrack music would normally do, by suggesting visuals to accompany the music (like the line, “I don’t even know how the gun got in my hand” on “Whispering Streets”). But that’s part of the fun of this approach to music. And Barry Adamson is still basically the only one doing what he does.