A guide by Syd Fablo, Bruno Bickleby, and Patrick.

Introduction

This is a guide to the music of Ornette Coleman. Albums are listed chronologically by recording date, broken down into multiple periods of his life and career and supplemented with biographical information. Outtake and various artists collections are shown indented and with smaller font and images. Bootlegs are listed, indented, but images and details are provided for only a few selected bootlegs that are of particular significance. Guest and sideman appearances are listed separately toward the end. Book, film/video/TV, and web site resources about or featuring Ornette are listed at the end. The authors also provide curators’ picks and some other items of interest at the end. While there are some compilations and box sets of Ornette’s work available, note that (with one exception) most focus on only a narrow period of time or are explicitly record label specific — the most significant of the label-specific ones being Beauty Is a Rare Thing: The Complete Atlantic Recordings. It is somewhat unfortunate that many of Coleman’s recordings are currently out of print. Moreover, unlike the deluge of archival, outtake and bonus material issued for certain other famous musical contemporaries of Ornette, there has been comparatively little of such material by him officially released to date.

A Brief Biography

Birth Name: Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman

Born: March 19, 1930 (or possibly March 9, 1930), Fort Worth, TX.

Died: June 11, 2015, New York, NY.

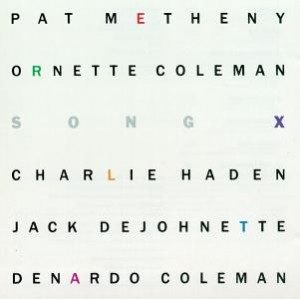

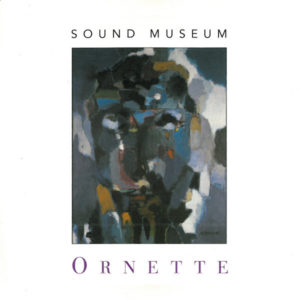

Ornette received almost no formal musical training, and was a noted autodidact. Reports of him being unable to read music are often exaggerated in order to present him as a kind of primitive musical savant, rather than as someone from humble roots who willfully bucked convention. Though he began playing music professionally while still a teenager, it was not until he was in his late 20s that he recorded as a bandleader and he was almost 30 years old before he found success as a solo act — rather late by typical jazz standards. His music was resisted and disliked by many, but he showed an uncommon amount of “grit” in sticking with it despite adversities and setbacks. Listeners tend to have a “love him or hate him” sort of reaction. Usually described as shy (i.e., introverted), he also struck many as an unusual guy for his mannerisms and outlook on life. He eventually developed his own musical theory that he dubbed “Harmolodics”, which he insisted can be applied to how one conducts their own life and to other artistic forms. Often he described himself as a composer who performs. “Lonely Woman” was his first “Harmolodic” composition, and is perhaps his best-known song. One-time collaborator Pat Metheny said about him, “Ornette is the rare example of a musician who has created his own world, his own reality, his own language – effective to the point where emulation and absorbtion [sic] of it is not only impossible, it is simply too daunting a task for most musicians to even consider.” His career (and fortunes) ebbed and flowed, with periods of intense activities and long stretches of public inactivity. He nonetheless came to be regarded as one of America’s greatest musical innovators. He also had a considerable art collection, and partly due to those interests notable contemporary artworks were reproduced on many of his albums, on the cover, back and/or inserts. At least after achieving career success, he was a dapper dresser, often wearing brightly colored custom made suits. His sister Truvenza (Trudy) Coleman also had a musical career, though she did not work with her brother professionally.

Legend

🎷🎷🎷 = top-tier; an essential

🎷🎷 = second tier; enjoyable but more for the confirmed fan; worthwhile after you’ve explored the essentials and still want more

🎷 = third tier; a lesser release, for completists only

Continue reading “The Shape of Jazz to Come: A Guide to the Music of Ornette Coleman”