A guide to the music of Tom Zé. His professional musical career spanned half a century (and counting), though today many of his recordings are out of print — even in his native Brazil. What is available in the United States tends to skew toward his later recordings, which has the unfortunate effect of placing some of his finest material out of reach. His solo recordings are listed below divided into two time periods. His collaborations are listed separately — some being mere guest appearances while other are more extensive. Pursuant to the legend below, ratings are assigned to each, though Zé hardly has any bad releases so bear in mind these are just relative assessments. Links to other resources, including books and films, are provided at the end.

This is still under construction.

Sung and Spoken Journalism (Imprensa cantada e falada): A Brief Introduction

Birth Name: Antonio José Santana Martins

Born: October 11, 1936, Irará, Bahia, Brazil

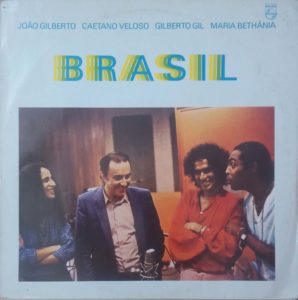

Antonio José Santana Martins, who adopted the stage name Tom Zé, was born in the dry interior region of the Brazilian state of Bahia. He has described his hometown of Irará as “pre-Gutenbergian” (in reference to the inventor of the movable type printing press). His father won the lottery, which allowed his family to live comfortably in an otherwise poor and arid rural region. He moved to Salvador, the largest city in Bahia located along the Atlantic coast, to attend the University of Bahia. He studied music. He had an interest in composers like John Cage and Charles Ives. Although Brazil had a troubled legacy as a former Portuguese colony (and briefly was the seat of the Portuguese capital), and was the last country in the western hemisphere to ban slavery, social democratic president João Goulart made some modest reforms and the Brazilian universities recruited professors from Europe to bolster their musical (and other) programs. A military coup in 1964, supported by the United States, overthrew Goulart and installed a series of military “presidents” who ruled until 1985. Zé relocated to São Paulo, was associated with a collection of leftist intellectuals in the 1960s, and became part of the tropicália (A/K/A tropicalismo) movement, the most prominent members (tropicalistas) of which were mostly Bahian too. The (AI5) “coup within a coup” in 1968 brought harsher treatment of leftists and some of the tropicalistas. While considered a key part of tropicália, he also seemed outside it at the same time, never contained by its key precepts despite his obvious sympathies and contributions. His career faltered as the 1970s wore on. By the 1990s he was considering working at a gas station when he was approached by the U.S. musician David Byrne (of Talking Heads), who had come across a Zé record and later sought him out (with the help of Brazilian-raised musician Arto Lindsay) to sign him to a new label. Byrne was largely responsible for reviving Zé’s commercial career and introducing him to international audiences. Though in many respects, Zé’s albums on Bryne’s Luaka Bop label are somewhat over-represented in English-speaking countries.

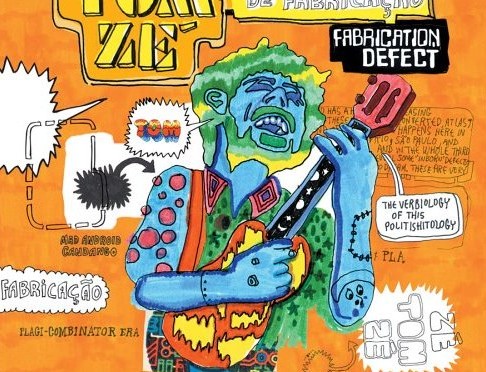

Caetano Veloso has described Zé’s tenaciously archaic yet inventive approach to music as “bizarrely elegant” and his attitude (reflected in his music too) as having an “ironic, distant sense of humor” that is “at once intimate and estranged[.]” An incident on a plane that Veloso recounts is a fitting summary of a common effect of Zé’s music, when Zé made an absurd request for a particular drink (cachaça) on the plane, then, when it was not available, demanded the stewardess to stop the “caravel” (mid-flight) so he could leave, noting, “we were unnerved by the determination with which [the demand] was made, the sheer imposition of his will.” Veloso was impressed with how “the sincerity of [Zé’s] defiance exposed the absurd pretense of refinement” around him. This was in so many ways a fitting metonym for the entire tropicália movement. (The anecdote also recalls Bertolt Brecht’s short story “Geschichte auf einem Schiff [Story on a Ship]”). Recurring themes in Zé’s music involve tilting against colonial legacies (in the sense of Frantz Fanon) and making demands that emerge from leftist ideologies deemed impossible in his own time. Zé considers himself a performer of limited means. He has referred to at least some of what he does as sung and spoken journalism. In the 1970s he experimented with what can be called a homemade sampler, and has long utilized homemade instruments (like Harry Partch, or Tom Waits in the mid-1980s and early 90s).

After his comeback in the early 1990s, the influence of animated Brazilian folk dance musics from northern regions, like the forró and coco of Luiz Gonzaga and especially Jackson do Pandeiro, were more apparent in his own recordings. He continued working long after others would consider retirement. There is a tenacious sense of experimentation that is constant throughout Tom Zé’s career. He has toured internationally, though availability of his albums outside Brazil can be limited, even his most famous recordings.

Solo, Part I: Bahia to São Paulo

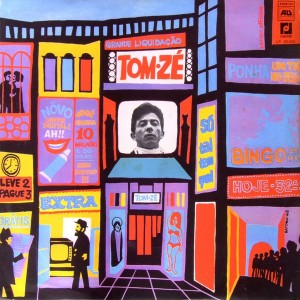

Release Notes: available on CD, vinyl and digitally as Grande Liquidação

Recorded:

Personnel:

Producer(s): João Araújo

Tier: ♻♻

Key Track(s): “São São Paulo”

Review: Continue reading “The Lollipop of Science (O Pirulito da Ciência): A Defective Guide to Tom Zé (Um guia com defeito para Tom Zé)”