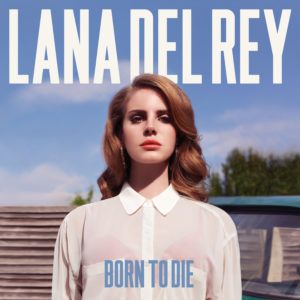

Lana Del Rey – Born to Die Interscope B0016425-02 (2012)

Upon her breakthrough to international audiences, Del Rey elicited a polarizing reaction. After hearing buzz about her, my first exposure to her music was her terrible appearance on the TV show “Saturday Night Live.” I wrote her off as another pop music bimbo. Born to Die, her breaththrough album, is really in the classic pop tradition of having one or so great singles and a lot of filler.

“Video Games” is indeed a pathbreaking pop song — amazing in that it has no syncopated beat and a glacial tempo. It is great precisely because of the sympathy it elicits for for the song’s protagonist, who debases herself in desperate and self-defeating attempts to achieve her ends against and within seemingly hopeless structural social constraints only to (eventually) realize the power to claim her own identity. Contrary to a literal, “Stand By Your Man” reading of the lyrics, which should be discarded, it is an identity of numb isolation and doubt, but it is her own, and a product of her own free will. When she sings, “It’s you, it’s you, it’s all for you” the listener should think of the scene in the horror film The Omen in which the nanny, under the influence of demonic forces, climbs on a ledge of a mansion during a gala party and declares, “Look at me, Damien! It’s all for you,” then jumps off the ledge and publicly hangs herself. The song deftly implies a whole lifetime spent absorbing a gender role and the learned helplessness that goes with it. The protagonist’s assigned role requires external validation because “they say that the world was built for two / only worth living if somebody is loving you.” Every soaring crescendo of the orchestral backing is an anti-climax. It ironically presents a kind of sorrowful self-realization that breaks free of the imposition of meaning enough to look back in from outside, from another perspective. By the end of the song, reflecting on how others say it is “only worth living if somebody — is loving you,” Del Rey sings, “Baby now you do — now you do.” The repetition of “now you do” is flat. There is no joy in Del Rey’s vocals. She hums a line, but sounds puzzled and almost baffled. The strings disappear. There is a background vocal of “now, now you do / now you do,” which plays the role of society reinforcing the “proper” perspective. She sings “now you do” again in a flat way. A harp plays a glissando and a piano plays a brief repeating melody as her voice has dropped away. Del Rey is absent as the song concludes. The conditions imposed by society have been satisfied, but the song subverts that supposed achievement. Instead, the protagonist, in her socially imposed role, effectively commits suicide like the Omen nanny, opening herself to new possibilities. That realization points toward a neutralization of those structural constrains. She can now find her own meaning. She can be miserable if she wants. No longer does she have to feel pressured to enjoy debasing herself to please someone else. This reading comes through listening to the song itself, because the ironic and sarcastic tone of the vocals contradict the literal text of the lyrics. Del Rey did make a music video for the song herself. It features webcam recordings of her leaning against a wall doing some come-hither posturing interspersed with various clips of guys doing tricks on skateboards and paparazzi footage of a drunken celebrity falling down. Just like the skateboarders do tricks for attention and celebrities make a spectacle of themselves, this emphasizes the performative role the song’s protagonist plays. And if she dons her persona just to take power however she can, then maybe she is just adding a twist on what Madonna did decades before (the so-called “Madonna question”), in a time when sexual provocativeness no longer has much effect or shock value.

Some of the songs have Del Rey singing with husky vocal histrionics in the mold of Amy Winehouse. Lots of the filler has her peddling guilty pleasure trash only marginally more sophisticated than what Britney Spears built her career on. “National Anthem” and “Diet Mountain Dew” are the kind of ghetto fabulous novelty pop that fueled Gwen Stefani‘s “Hollaback Girl.” The songs are produced in a way that is mostly predictable and uncomplicated. There is an emphasis on accessible hooks for an era in which hip-hop dominates pop sensibilities.

Born to Die skews towards fun, throwaway pop, while, in spite of that, the album is carried by the success of a couple/few songs — “Video Games,” “Born to Die” — that are something else (more) entirely. The entire second half of the album is instantly forgettable. Amazingly, Del Rey would shift the emphasis to the deeper aspects of this album in her later work. The bimbo act may really have been a means to other ends after all, even if there are many reasons to question that on this particular album.