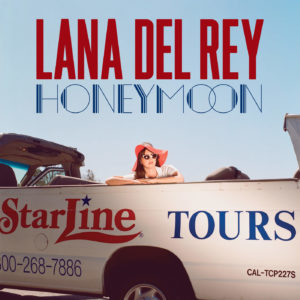

Lana Del Rey – Honeymoon Interscope B0023750-02 (2015)

Calling Honeymoon “bubblegum nihilism” hits pretty close to the mark. It calls up a dark, dispirited mood — not far off from old, melodramatic movies like Sunset Boulevard, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolfe? or twisted latter-day recreations from the likes of David Lynch — set against sparse electronic beats dressed with occasional strings and chamber pop instrumentation. Del Rey’s vocal tone, timbre and range are not especially memorable, and the lyrics are so often raw. But those qualities actually suit the music. The tempos are all slow, much slower than the songs seem to call for. The backing as a whole drifts off, a kind of indistinct mass of the vaguely familiar. Her vocals pierce through the music, but in a disinterested way. She conveys a kind of apathetic disgust with everything around her, especially when her surroundings are at their most glamorous. The quality of stepping back from it all is perhaps the most admirable one she advances. There is also hedonism and a kind of electronic new ageism lurking behind much of this. Yet aside from that there is also a clear admiration for certain refined strands of bohemian culture.

“Freak” is one of the best songs. A slow recurring guitar riff recalls a film noir rather than goth/rockabilly version of The Birthday Party‘s “Say a Spell” (from Mutiny!). Playing a guitar chord that way turns the harmonic elements into melodic ones as each note stands almost alone.

“The Blackest Day” is another good one. It characterizes the lyrical approach of the album, with emphasis on cataloging surrounding artifacts and discrete, quantifiable experiences to allow Del Rey to convey melodramatic feeling in her vocals. Thematically, this and other songs still fit what one critic called Del Rey’s penchant for “exploring the internal worlds of numbed female characters posing as arm candy[.]” Though on Honeymoon that is toned down a bit, and more generalized.

The single “High on the Beach” probably epitomizes the entire album’s sound the best. There is a deadpan melancholy that just seeks to withdraw. It practically suggests going catatonic, in a trendy and visible way. Del Rey sings with a breathiness that seems slightly disaffected — a comparison to “Cat Power-does-Chris Isaak” is fair (as is calling herself a “gangster” Nancy Sinatra, for that matter). She seems to do that not to appear as a stereotypical weak and submissive woman but rather more like the way punk singers sang off key on purpose. The lyrics refer to independence and self-sufficiency, though without much in the way of specifics. Her vocal phrasing is informed by what is old and classy, but her vocals are juxtaposed against what is current and disreputable. This conveys a sense of power to handle, in whatever limited way, those disparate, incongruous elements, against the odds. It is an approach employed in similar ways in photographer Robert Mapplethorpe‘s works that mashed up art deco with gay subculture.

In terms of purely musical technique, she seems to draw some obvious inspiration from singers before her. The closer, a cover of Nina Simone‘s “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood,” positions itself somewhere in the realm of Simone’s occasional forays into twisted, orchestrated rock like the title track from I Put a Spell on You. It also orients the listener, placing Del Rey in her desired continuum of pop music history.

There is nothing particularly groundbreaking in the backing instrumentals. All the songs adhere to the structure of conventional pop songs. Even the specifics seem familiar. Take “Religion,” a poppier echo of The Raveonettes‘ hazy, beat-heavy retro rock.

But, frankly, the gloomy noir elements elsewhere, like on the title track, vaguely recall a (much) more mainstream/commercially palatable “Hollywood sadcore” take on the style of Lydia Lunch‘s Queen of Siam (“Gloomy Sunday,” “Spooky,” “Knives in the Drain,” “Lady Scarface,” “A Cruise to the Moon,” etc.), with electronic dance/hip-hop beats and filmic orchestration in place of no-wave punk rock and cabaret jazz. And Del Rey has that bubblegum aspect that Lydia Lunch has, well, none of, just as Del Rey has none of Lunch’s menacing sarcasm. Honeymoon‘s dark electronics with dramatic singing is also close to, say, Carla Bozulich without the pretension and more emphasis on camp, or even a more dejected and straightforward version of some of David Sylvian‘s (ex-Japan) art pop.

So is Del Rey just appropriating and co-opting elements of creative and independent music of prior decades, like a cultural pirate, or is she turning mainstream culture against itself, like a “culture jammer”? Is it even possible to introduce elements of underground music into mainstream commercial culture without betraying those building blocks? Is she a feminist or just an individualist? Is her sincerity merely being sensationalized by the media industry for mass consumption, or is is her public image entirely just a fake persona? Is she really just a full-bore part of the establishment media, and not really a critic of it at all? These are central questions an album like Honeymoon presents.

Of course, it is obligatory to mention the highly stylized persona that Del Rey has used to put across her music. This persona — part femme fatale ingénue, part stoner washout, part vulnerable introvert, part insecure hipster, part deluded mallrat, and part ambitious artiste — is an odd thing. She broke into international recognition largely through an online music video that she directed, edited and partly filmed herself. Whatever one thinks about her persona, good or bad (or some of both), it is one she largely crafted herself. It is wrong to castigate her for creating a persona in the first place. Even the painter Georgia O’Keefe can be said to have done the same in becoming an artistic celebrity. Every personality, public or private, is to a degree a mask over the void of being. Such masks allow for and mediate a social conception of the self. To the extent that Del Rey puts forward a musical vision in which every person is worthy of consideration, even one as flawed as her persona, maybe that is a good thing. There also is a curious aspect of this persona that suggests ordinary people can follow suit in order to take charge of their own lives in some way, at least by taking responsibility for establishing their own desires and giving no ground to acting in conformity with those desires. In this way it might even be said she is merely trying “to be just extreme enough to be an ‘effective extremist.'” In any event it is a far cry from the stance of “mogul” pop.

This album is not entirely successful. The cynicism of Honeymoon ties it to precisely that which it claims to break away from. Is her position against and outside those things — like Céline Dion’s music but for younger, hipper audiences — just a coping mechanism under late capitalism, and therefore a reinforcement of it? And yet, the pleas to be a “freak like me” and Del Rey’s rejection of some typical major label promotional activities (combined with a continuation of others) do suggest an ambiguous relationship with mainstream success. It is an old dilemma. While she has already stepped back, musically, from the element of “having it both ways” (as a victimized yet manipulative femme fatale) evident in her breakthrough hit “Video Games,” Del Rey will have to go further to really be a countercultural force that undermines — or at least minimally overcomes — the media industry from the inside (what the somewhat similarly mall/Hollywood-inspired filmmaker Michel Gondry has largely failed to do since his early music videos gained him notoriety). That especially goes for her music videos. But Honeymoon shows that she might well have both the inclination and talent to do so. This certainly stands above what she has done before at album length. The best songs are the best generally because they introduce a larger stylistic gap between the vocals and the backing, forging ahead in spite of that gap, while the lesser songs tend to come across more like straight genre exercises. There are not any obvious missteps — though the T.S. Eliot recitation “Burnt Norton (Interlude)” is jarring, and some of this just treads water (“24”). And there is much less reliance on guilty pleasure trash pop than on her breakthrough Born to Die. The best songs (“High on the Beach,” “Freak,” “Honeymoon,” “The Blackest Day,” “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood”) are really quite good, maybe even great. But the album could have used a few more great songs to be a great album as such. As it stands, Honeymoon still suffers somewhat from the problem of being a really good EP padded out to album length. Still, even just looking at the singles from the album, it is certainly an achievement to place music this depressing into the pop charts at all, which hasn’t happened much since the “grunge rock” era. On the whole, this might just be a personal turning point when the price of fame has sunk in enough for Del Rey to feel the sting, but also while she still holds enough widespread appeal to become a sort of anti-hero for a disaffected age. Or not.