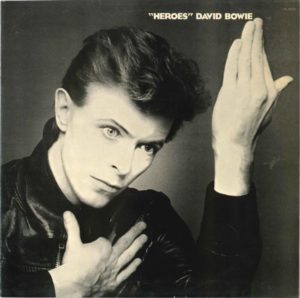

David Bowie – “Heroes” RCA Victor PL 12522 (1977)

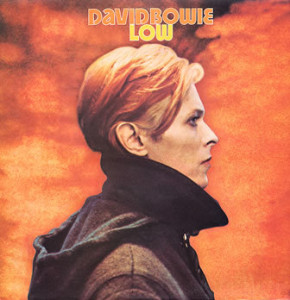

“Heroes” has remained one of David Bowie’s finest albums. Part of his so-called “Berlin Trilogy”, it roughly follows the same format as the predecessor Low, with the first side devoted to art pop experiments and the second side (mostly) devoted to quasi-ambient instrumentals. But where Low was a poppier version of German “krautrock”, with an emphasis on intensity of feeling, “Heroes” puts more emphasis on songs as such and adds just a bit more disco influence. The music is strange in that it goes in the opposite direction of commercial trends of the day, drawing from left-field European rock and twisting carefree disco dance music with harsh industrial noise while still eschewing the sound of the burgeoning punk movement. Bowie was continuing to chart his own path. And, perhaps, that is part of what makes this elusive music so enduring.

The opening “Beauty and the Beast” is a great one. While Bowie’s disaffected, contrarian and almost deadpan vocals are something of their own statement, the glimmering guitar and relentlessly bouncy beat fits comfortably in the disco era, even as the song’s icy, menacing edge is different from a typical disco dancefloor hit. “Blackout” is another song with hints of disco rhythms. Of course, the likes of “Golden Years” and “Stay” (from Station to Station) and “Fascination” (from Young Americans) had already ventured into disco territory in the prior two years.

“Joe the Lion” is kind of a tale of staggering, hazy, late-night club life, and the hangover. Once again Bowie’s vocals are a kind of contrarian abstraction. The song as a whole recalls Iggy Pop‘s minor hit album The Idiot (produced by Bowie), especially stuff like Iggy’s Stooges nostalgia song “Dum Dum Boys” and even the slower more minimalistic “Sister Midnight.” Guitarist Robert Fripp of King Crimson is on the album on lead guitar, and adds distinctive character to songs like “Joe the Lion.” The mostly instrumental “V-2 Schneider” (in reference to the Nazi V-2 Rocket, which inspired the plot of Thomas Pynchon‘s novel Gravity’s Rainbow), has similar textures to “Joe the Lion” with a more laid-back delivery.

The title track is a Bowie classic. It is a romanticized mini-epic, complete with a kind of soaring and triumphant progression. Producer Tony Visconti used a kind of latched gating effect, in which one microphone was inches from Bowie, another was 15-20 feet away, and a third was across the room. As Bowie sang louder, the gates would trigger a more distant microphone and mute the others. This allows Bowie to begin singing the song by quietly crooning, nearly at a whisper, then sing loudly, then practically shout, while the distance of the microphones scales back the intensity of his near-shouting to a slower crescendo. The effect is something of an audio equivalent of the “dolly zoom” camera technique used in Alfred Hitchcock‘s film Vertigo. Behind the vocals Robert Fripp plays guitar with “tuned feedback” and Brian Eno contributed electronic effects. The album was recorded in West Berlin, during the Cold War division of Germany. The name of the song references the Neu! song “Heroes” (from Neu! ’75). The song title is in ironic quotes, though the intended irony is somewhat difficult to detect in the music itself. Yet the drumming is quite different from the “motorik” style of Neu!, more conventional, with the bass kick drum nearly inaudible in this instance. The song’s lyrics, though, deserve some unpacking. They describe a couple “standing by the wall”, alluding to the Berlin Wall that then divided the city. While Western propaganda (still) repeats the fable of the wall going up to keep East Germans in, the reality was that the wall kept Western saboteurs out while also helping to limit a “brain drain” on educated Eastern workers to freeloading Western corporations. Bowie performed the song in 1987 against the Wall as part of the “Concert for Berlin.” That concert is often cited as prompting the wall be torn down (which it was in 1989). Even the right-wing Federalist Society credited Bowie for his role. Of course, the fall of the Berlin Wall allowed the Western Saboteurs (like Jeffrey Sachs) back into the East, with predictably catastrophic consequences. Most former East Germans later said they preferred being behind the Soviet “Iron Curtain”, and, according to Der Spiegel, “20 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, 57 percent, or an absolute majority, of eastern Germans defend the former East Germany.” So Bowie’s song should be viewed skeptically. But no doubt it is one hell of a catchy tune and this is a spectacular recording.

The second half of the album turns to mostly instrumental songs with ambient qualities — just like Low and Neu! ’75. These are still songs, though, and are much more compact than anything on Low or Neu! ’75. “Moss Garden,” complete with Zen-like washes of sound and Bowie playing koto, is arguably the finest instrumental track on the entire Berlin Trilogy. “Sense of Doubt” and “Neuköln” are both solid tunes too.

The album concludes with “The Secret Life of Arabia,” which has vocals and goes back to disco influences, albeit now with vague middle-eastern references. This scales back the experimentation of the album, and ensures that pop songs remain the focus.

This album was Bowie’s least popular since his Ziggy Stardust breakthrough. The title track has become one of his best-known songs, though at the time — like most of Bowie’s late-1970s singles — it wasn’t a hit. While it lacks the sense of wonder and daring of Low, the taut, punchy rock songs of “Heroes” are still pretty great. What this lacks (if anything) in terms of eye-opening creativity it makes up in determined consistency.