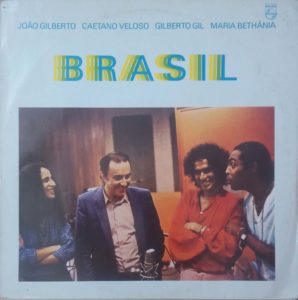

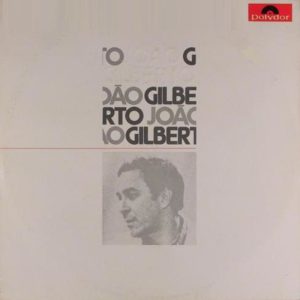

João Gilberto, Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil & Maria Bethânia – Brasil Philips 6328 382 (1981)

There is an old observation that the (western) musical stars of the 1950s and 60s often struggled for relevance in the 1980s. Bo Diddley, Little Richard, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan…these aging stars may have retained some popularity but their work in the 80s is generally critically reviled — and they were definitely less popular and less commercially successful than before. But why? My own view is that these changing perceptions and fortunes rested on wider changes in the sociopolitical context, namely the ascendancy of neoliberalism as represented by a shift in a balance of power between labor and capital that undermined the relative power of these stars’ old audiences bases. At least, all this makes perfect sense when looking at the United States, where those older popular music stars were once associated with revolutionary and iconoclastic new ideas that challenged establishment power. What about Brazil though? Brazil was ruled by a reactionary military junta from 1969 to 1985. Every one of the top billed musicians on this collaborative album Brasil was associated with the (intellectual/middle class) political left — Veloso and Gil were jailed and/or exiled by the junta for a time and Gilberto went into self-imposed exile too. But by the 1980s, the junta was fading and its power loosening. In other words, the sociopolitical climate in Brazil was changing in a manner directly opposite to the United States. No doubt, the junta still held power in 1981 and, in a way, Brazil was changing in order to converge and collaborate with the neoliberal Washington Consensus. But the sociopolitical vectors here were nonetheless in opposite directions. This was much like the situation in Spain with the decline of the fascist Franco regime. So comparisons to, say, the Spanish flamenco artist El Camarón de la Isla are apropos. New opportunities were presenting themselves in Brazil and Spain that instead seemed to be becoming foreclosed in the United States.

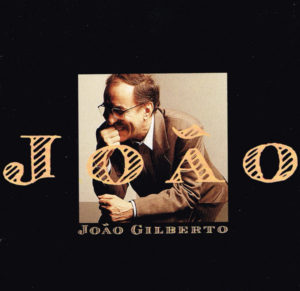

Brasil is a collection of collaborative recordings that speak to a sort of traditional pop sensibility but with a modern (leftist) twist. Most of the artists here were already starting to drift into irrelevancy, except for João Gilberto who maintained a quite isolated independence and made some of his very best recordings in the coming years. The problem was also that in the absence of the junta these artists mostly just accommodated themselves to neoliberal imperatives and their music was accordingly listless and vapid, though sometimes adequately mediocre. But on Brasil there is a spark of challenge. There is a sense of courage in making a limited yet persistent challenge to the ideology of the reactionary junta. As someone later said about Greece decades later, “To persist in such a difficult situation and not to leave the field is true courage.” This album represents a unique historical juncture when challenges to the junta’s regime had potential, and this album reflects those possibilities. Sure, it occasionally drifts into regrettable synthesized production treatments so common of the day, but only slightly and not to much overall detriment. The subversive aspect of this album is, unusually, its laid-back demeanor, which instills both a sense of introverted, existential anxiety and a relaxed charm that suggests social changes will still offer an environment that is enjoyable. It also melds the old and the new in a way that has a high degree of difficulty.