Link to a film review:

Tag: Drama

Minnie and Moskowitz

Minnie and Moskowitz (1971)

Universal Pictures

Director: John Cassavetes

Main Cast: Seymour Cassel, Gena Rowlands

Cassavetes’ Minnie and Moskowitz is the story of a couple’s oddball romance. The basic plot is adapted from that of Marty (1955). But Cassavetes puts a wider social chasm between the two main characters. Seymour Moskowitz (Seymour Cassel) is a sub-proletariat hippie who works as a car park attendant, whose mother sees him as a hopeless case with a downward trajectory in life. Minnie Moore (Gena Rowlands) is a museum curator who rubs shoulders with wealthy art aficionados, though she comes from a middle class background. Despite characteristically uncomfortable scenes and intensely raw acting, this is Cassavetes at his most conventional and accessible. Yet this film succeeds on multiple levels, not just as a light comedy/drama. The main characters have a tumultuous relationship. There is nothing easy about them coming together. They have plenty of inhibitions, brought on by the stress and fears and discrimination and loneliness and limitations of their individual lives. It is hard for them to let go of those things, however much misery those things bring them. And the people around them are mostly selfish and rude, or just unable or willing to open up to others. Minnie, in particular, has a hard time accepting Seymour, because she is part of a much higher social strata that tends to sneer at the likes of him. Her real-life husband Cassavetes plays her (ex) boyfriend Jim, a married man who won’t leave his wife. She is surrounded by people who seem only interested in how she fits into plays for status — Jim with his stable of women or a blind date (Val Avery) trying to be less of a sad sack without a wife like a successful guy like him “should” have.

But the real heart of the film is that the tumult and conflict all serves to bring two people together. Their relationship is a choice, and they choose to transcend the many, many obstacles put in its way. The sweetness of Minnie and Moskowitz is that it is a romance tale that suggests social inequities can be overcome, and that relationships can play a part in making the world a more accepting place. This is what distinguishes it from Marty, which is a wonderful movie with superb acting but one that relies upon the (essentialist) idea of characters settling for something and discovering what they “really” are and “really” want. Cassavetes’ film is about the characters becoming something more than what they were at the start. That is especially true for Moskowitz, who goes from being someone drifting along on nothing more than simple pleasures to having a larger purpose. This may not be Cassavetes’ best or most ambitious work, but it is one of his most likable films.

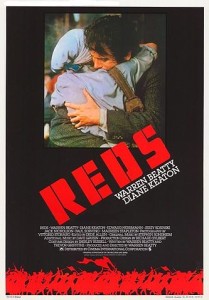

Reds

Reds (1981)

Paramount Pictures

Director: Warren Beatty

Main Cast: Warren Beatty, Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Edward Herrmann

Although there is frequently an accusation of “Hollywood Liberalism,” after the McCarthy witch hunts of the 1950s, the political left had a fairly low profile in Hollywood post-WWII. During the “New Hollywood” movement, beginning in the late 1960s, that changed, somewhat. In the early 1980s, at the tail end of that movement, there were at least a couple of politically leftist epics — no less — that represented some of the last and best examples of what was possible for the political left working in conjunction with big business movie making (the other being Heaven’s Gate (1980)).

Reds is the biographical story of John “Jack” Reed (Warren Beatty), the journalist and author of Ten Days That Shook the World (1919), an account of the October (Bolshevik) Revolution in Russia, and his companion Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton). Reed is the only American buried in Red Square in Moscow. The film opens at the beginning of WWI. One of the finest moments in the entire film comes in the first few scenes when Reed, a journalist just returned from the front in Europe, is asked to speak at a high society gathering about the real cause of the war. He stands up and says, “Profit.” He then immediately sits back down. Could there be a clearer explanation in any number of words? Interspersed with the historical dramatizations are documentary interviews with “witnesses,” people who knew Reed and Bryant long ago retelling anecdotes for Reds. Some were friends, while others don’t have anything particularly kind to say. Jack Nicholson portrays playwright Eugene O’Neill. His misanthropic character has clearly been a model for plenty of other Hollywood actors in later films.

Many leftists despise Reds, often because it subordinates the October Revolution to a romantic melodrama. This seems unfair. If the romantic drama were not in the forefront, this would not be a Hollywood movie. As it is, there are hardly any Hollywood films that paint authentic leftist revolutionary activity in such a positive light. Of course, Michael Cimino‘s Heaven’s Gate overcomes all the difficulties with Reds‘ treatment of romantic melodrama (Kris Kristofferson ends the movie married and bored on a yacht) — though at the same time Cimino’s film was butchered to a condensed version that bombed, only to be resurrected with a director’s cut later on.

It is difficult to maintain a suitable pacing throughout an epic. Reds does well in that regard, even if things slow a bit toward the end when during the midst of the post-revolution civil war the film, paradoxically, focuses on the powerlessness of the characters. There are bits of Ten Days That Shook the World that might have added some levity, like when the only restaurant open after Reed investigates the storming of the Winter Palace is a vegetarian restaurant called “I Eat No One” with a picture of Leo Tolstoy in the front window. But, such changes would, again, make this something other than a Hollywood romance film.

As it stands, Reds is one of Hollywood’s finest dramas of the early 1980s. Beatty and Keaton are fantastic, Keaton as someone from a privileged background desperately striving to cultivate cultural capital in the artistic/journalistic world and Beatty as the slightly vain and adventurous but nonetheless immensely talented figure who made important contributions to the historical documentation of the October Revolution in the English language.

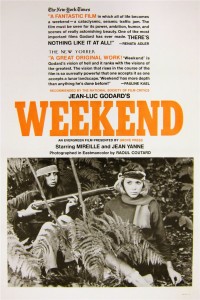

Week-end

Week-end (1967)

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Main Cast: Mireille Darc, Jean Yanne, Jean-Pierre Léaud

…and Godard enters his Maoist phase. You’ve probably heard or read summaries before. This movie is about the collapse of the capitalist system that sustains the Western World, and the idea that more meaning in life will emerge after its collapse. But the best part is that for all the depravity and vice, it’s hard to tell exactly when Godard is joking. Oh, and the visual metaphors are astoundingly unique. This one tends to be a favorite of die-hard Godard fans, and count me among them.

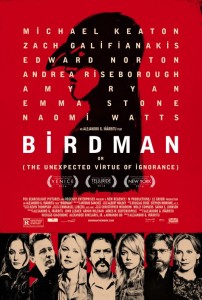

Birdman

Birdman: or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014)

Fox Searchlight

Director: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Main Cast: Michael Keaton, Edward Norton, Emma Stone, Zach Galifianakis, Naomi Watts

Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous: Actors Edition.

Birdman is a film that wants to be deep. It concerns an aging actor Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton), whose career has become defined by a title role in a superhero movie franchise. But now he is organizing (as writer, director and actor) a stage adaptation of the Raymond Carver short story collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Love on Broadway. Unhappy and frazzled, he brings in a well-known stage actor Mike Shiner (Edward Norton) as a replacement for one of the male stars. His daughter (Emma Stone), back from drug rehab, is “assisting” him as a way to keep her occupied. The film builds on intense scenes with long shots, set in the bowels of the theater, on the stage, and in the dressing rooms. Intermittently through the film, Michael Keaton’s character hears a voice in his head, and he seems to possess the ability to fly, move objects with his mind, and otherwise really be a superhero — or is this just a psychotic break brought on by the stress of the theater production?

The early part of the film sets up the conflicts, between the actors in the Carver adaptation and between Riggan Thomson and his legacy. Mike Shiner is a talented actor who we are to believe exists in two diametrically opposed realms: that of the “real world” where he is despised, impotent and rejected, and that of the stage, where he is adept, creative and appreciated. To impress the importance of Acting and the Theater, his character, and the others, behave badly and obnoxiously, parading about naked, smashing things in bars, and engaging in public arguments and fights. The main characters storm about the building, often met with bewilderment by the theater’s staff and technicians. Yet the staff and onlookers seem powerless to engage any of this. They are onlookers, not able to play a role in the tribulations of the Great Artists. The last half of the film sets out the resolution of those early conflicts. Michael Keaton gets most of the screen time toward the end. The ending, as we’ll see, feigns ambiguity.

The fatal flaw of this film, except for pretensions to depth that it doesn’t earn, is that it relies on a con. While Riggan Thomson seems to want to make deep art not just commercial movies, the Thomson character is always obsessed with status and power. He has a lot of money (financial capital), which, by personally putting up considerable funding for his play, he attempts to trade for greater recognition as an artist (cultural capital). In this, the theater is somehow seen as loftier in a hierarchy of arts, the audience of Broadway plays deemed more significant than the (presumably) middle-American moviegoers (and Times Square tourists) who liked Thomson’s turn as Birdman in the movie franchise. During a run-in with a theater critic in a bar, who calls out Thomson for his attempt to convert his movie celebrity into a different kind of cultural status on Broadway — and rather implausibly states in direct terms her role as a guardian of middlebrow tastes who must oppose such conversions of social capital — he angrily proclaims what a risk he’s taking. As the audience, we are to forget that this risk is just a gamble, like any other in (casino) capitalism, from a player who simply started the game with more chips than the others. The critic says her complaint is that Thomson is taking up theater space that could be put to better use (we are to infer she means someone with pre-existing cultural capital in the New York City theater scene), and promises to destroy the play with a scathing review, confident that she alone holds the power to do this (something the film undercuts, given the insatiable craving that fans seem to have to see Thomson in, well, anything).

There is another, earlier scene in which the daughter excoriates Thomson for failing to understand his insignificance — apparently unaware that this is the set-up for an old joke. That scene sits almost in isolation for a time, until the final scenes of the film provide a rebuttal. By the end, we hear that the voice in Thomson’s head (it is the Birdman character) explains the truth to him, and on the question of whether he is a superhero or a psychotic, his daughter in the final scene appears pleasantly surprised that rather than committing suicide by jumping out a window, he might really be flying. Rather than convince her father of his insignificance, instead it is her who ends up convinced of his exceptionalism. She also instructs him about online social media — making a fool of oneself publicly is the new way to wield power over a fan base. He just needed to understand contemporary marketing tactics a little better, see? Other scenes in which tense family relations come up, seem to be resolved through professional prestige: if Thomson’s play succeeds commercially or critically (does this film see any distinction between the two, really?), then all his other problems are solved.

The film ends on a note seemingly lifted from the iconic Jimmy Stewart family film Harvey (1950), about an alcoholic man whose best friend is a giant rabbit who may or may not be a figment of his imagination. Yet there is none of the heart or sweetness of the Stewart film here. Yes, there is good acting, but the scenes in which the acting is prominently on display are constructed for maximum intensity — with long shot after long shot, many close ups and hand-held camerawork — all meant to focus attention on isolated emotional outbursts strung together in series. While Harvey might be dismissed as a naïve children’s film, it opens the possibility for different ways of looking at the world, in a way in which, from the standpoint of social status, Stewart’s character stands to gain nothing at all from his friendship with a giant (imaginary?) rabbit. In Birdman, Michal Keaton’s character simply looks for the most effective path toward the fame and fortune he desires. There is no question about the path he’s following. He just needs to out-compete the other actors out there in the mean world of professional theater. How?

Birdman suggests that there is Truth. It is masked. But the voice in Riggan Thomson’s head still tells him the something that guarantees his happiness. This is the religious/theocratic core of the script. Thomson succeeds or fails based on whether he recognizes this Truth sufficiently. What we are left with is an apology for fame and status seeking, justified by reference to some higher power that only the exceptional few can access. Left somewhat unspoken in Birdman is how Riggan Thomson came to be a major Hollywood actor. There is a trite story of Raymond Carver congratulating him as a child, convincing him to pursue acting as a career. But it takes much more than talent and desire to succeed in the world. Only people with certain social capital can pursue careers in the arts, often having family legacies in that industry, having wealth that allows for unproductive time spent on artistic interests. So, there is also a hidden fatalism in this film. Thomson is destined to a path, he only needs to believe in it enough. So, to paraphrase Bertolt Brecht from Geschichten vom Herrn Keuner, Riggan Thomson wonders maybe if there is a god, but in his wondering he already decided, and it seems he needs a god, because he would not act in such a way to achieve fame and riches if he could grasp any other way than what those fame and riches seem to guarantee for him in the world. So no existential angst for him. He is absolved of creating meaning for himself. He just listens to the voice in his head. This, supposedly, is the “unexpected virtue of ignorance.” Strangely, it seems lacking in virtue. Greed is good?

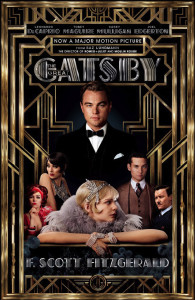

The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby (2013)

Warner Bros.

Director: Baz Luhrmann

Main Cast: Leonardo DiCaprio, Tobey Maguire, Carey Mulligan, Joel Edgerton

It took only a few minutes for this film to turn me off so completely that I stopped watching. It gave the impression of someone who read F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s The Great Gatsby and hated every single page, and so decided to make a movie that took a completely contrary view of the “Jazz Age.” Fitzgerald was an astute critic of the upper classes. This movie adores the upper classes, and crams as many CGI effects (WTF!!!!) into every scene as possible. Hip hop songs, cartoonish sets and exaggerated caricatures abound. I keep thinking that somebody wanted to make this like the movie Moulin Rouge! Sure enough, this is directed by Baz Luhrmann, director of Moulin Rouge! Luhrman’s craft has hardened into formula by this point. The big scenes all have a telescoping zoom shot done in CGI, focusing on a microcosm of a larger, bustling world. This makes it seem like there is a focus on just on corner of the world, but really the tone is that this is a representative view of the world, that one could look anywhere and find the same basic “human nature” at work. The past is portrayed as a version of the present with different fashions — implying that the present is pre-destined. Luhrmann is an arch conservative, so it makes sense that he would balk at a sympathetic reading of Fitzgerald’s story. This film is an abomination and should be viewed by no one.

Mamma Roma

Mamma Roma (1962)

Cineriz

Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini

Main Cast: Anna Magnani, Ettore Garofolo

It is common to look at Pier Paolo Pasolini as a Marxist, but that is inaccurate, or at least, it presents an incomplete picture. What Pasolini took from Marx was a view of class relations. That is the focus of his second feature as a director, Mamma Roma. His directorial debut, Accatone (1961), was a story of a pimp and other people around him at the fringes of Italian society, told in a way that made him an anti-hero. It drew on the sort of perspective that Jean Genet had developed in writings like Journal du voleur (1949), making an existential transposition of the ideologies of virtue and fulfillment of dominant society to those of vagrancy, theft, and prostitution. Pasolini, like Genet, made his characters, who by accepted standards were the lowest of low, come across to the audience as sympathetic. They strove in different ways than “respectable” society, but they struggled and strove nonetheless.

Mama Roma is the story of a former prostitute (Anna Magnani) whose now former pimp is getting married. She plans to move from the rural backwaters of Italy to Rome and open a fruit stand. In doing this, she reclaims her 18-year-old son (Ettore Garofolo) to live with her for the first time. This involves something like a Beverly Hillbillies scenario. Mama Roma wants to take on a different social position, and to renounce and conceal where she came from. She comments in the film about how what she did in the past was to make possible her future, for her and her son. Mama Roma tries to win her son Ettore’s affections. She buys him a motorcycle. While they have a fun ride together, it is only at the level of consumer materialism that she can relate to her son. He ultimately finds material possessions unfulfilling. Ettore lacks the particular social ambition of his mother, and harbors some resentment that his mother has transplanted him to a city in which he is forced to take on new roles, such as work that does not interest him. Numerous incidents occur in which he tries to prove his worth to local ruffians and a girl. This includes a brazenly ill-advised attempted robbery that lands him in jail, at which point an illness takes his life. In the throes of illness, he repents, in a way, by reaffirming that he is who he is, and should not force himself into the expectations of a social strata that is not his own. The film ends with Ettore strapped to a table by his jailers, dying with his arms out, implying a crucifixion.

It is clear that Pasolini sees Ettore as the moral center of the film. He, eventually, takes on what the philosopher Parmenides called the “way of truth”. Mama Roma’s attempts to take on a new social position, in crummy high-rise apartments, are a betrayal of her rural roots. She follows what Parmenides called the “way of appearance”. This is portrayed in numerous scenes in which to take control of situations, or to avoid conflict, she lapses back to her old ways. In spite of her aspirations, the real Mama Roma is the part of her she denies. Ettore is pressured to have ambitions, and it is only when thrust into the milieu of city life that he finds himself in despair and ashamed of his roots. He rediscovers this by the end of the film, but only when his mortality catches up to him.

The script of this film is excellent. It explores the social field almost like a sociologist. There is much focus on the idea of social trajectory and momentum, and a rejection of those things at a fundamental level by insisting instead on a kind of radical egalitarianism of singular, unitary social standing. The film as a whole, though, is something of a failure. Pasolini was still in his early phase as a director. The influence of neo-realism is still strong. But the main problem is that the acting is inauthentic. Pasolini admitted that Anna Magnani was miscast, because she had never lived a subproletarian existence (her habitus was that of semi-autonomous peasantry and small-scale merchants, who emulate and reflect the lifestyles of of capitalists and the upper middle class). Magnani was not someone from the rural poor, and therefore she did not know that life. Pasolini had this to say in an interview:

“Well I’m rather proud of not making mistakes about the people I choose for my films . . . . The only mistake I’ve made is with this one with Anna Magnani — though the mistake is not really because she is a professional actress. The fact is, if I’d got Anna Magnani to do a real petit bourgeois I would probably have got a good performance out of her; but the trouble is that I didn’t get her to do that, I got her to do a woman of the people with petit bourgeois aspirations, and Anna Magnani just isn’t like that. As I choose actors for what they are and not for what they pretend to be, I made a mistake about what the character really was, and although Anna Magnani made a moving effort to do what I asked of her, the character simply did not emerge. I wanted to bring out the ambiguity of subproletarian life with a petit bourgeois superstructure. This didn’t come out, because Anna Magnani is a woman who was born and has lived as a petit bourgeois and then as an actress and so hasn’t got those characteristics.” Pasolini on Pasolini (1969)

While Mama Roma is engaging in concept, it also is less successful on its own terms than other Pasolini films. Accatone, for one, provides a more fluid verisimilitude. Mama Roma is something of a sequel, and suffers from all the limitations that such a label implies. The bawdy, direct humor of Pasolini’s later films is not yet present either, nor the intellectual commentary in his repurposing of classics. This is not one of Pasolini’s best films, but even Pasolini on an off day is something.

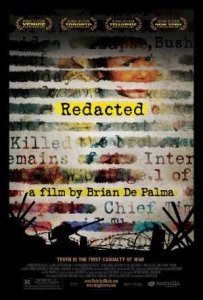

Redacted

Redacted (2007)

Magnolia Pictures

Director: Brian De Palma

Main Cast: Rob Devaney, Daniel Stewart Sherman,

Patrick Carroll, Izzy Diaz

Although director Brian De Palma won accolades in early European film festivals, Redacted was a commercial failure in the United States. It opened in barely more than a dozen theaters and hardly anyone saw it. That might be explained — in the post-Jaws manner of direct marketing — that the film wasn’t advertised enough. Regardless, it remains a difficult film to watch, but is still among the more significant made thus far about the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq.

The film does not devote itself to the reasons for the invasion and occupation, or the political motives for doing so. Rather, it takes aim at the withholding of the “facts” about what actually was happening during the occupation. As the film’s title implies, this is partly about the U.S. government covering-up and concealing what was happening, but perhaps more so the role of the media in enabling a deception on the American people who ostensibly enable the war and occupation. The story is fictional, but was based on real events involving the rape and murder of an Iraqi civilian by U.S. troops.

What has attracted the most attention is the technique of interspersing different perspectives. The film is presented as if assembled from a video diary by the soldiers themselves, footage from French and Arabic television crews, security cameras, as well as Internet videos. The notion of presenting multiple perspectives goes back to films like Rashomon (1950), though the extensive use of first-person video recalls the zombie movie Diary of the Dead (2007), which was released a mere week later. Like that zombie movie, the acting in Redacted has some weak spots, exacerbated by poor casting.

The central plot of the film involves a couple of clearly mentally disturbed soldiers who decide to rape a local girl who passes through their military checkpoint daily. Although they inform other soldiers in their unit, those others do little or nothing to stop them. In this way, De Palma frames the plot around something close to Hannah Arendt‘s famous notion about the “banality of evil”, developed when she wrote about the Nazi concentration camp administrator Adolph Eichmann (Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil). In a historical sense, the rape incident in Redacted resembles the My Lai Massacre from the Vietnam War, a story broken after the fact by independent investigative journalist Seymour Hersh. Following the rape, one of the soldiers, who was making the video diary throughout the movie, is kidnapped by insurgents and beheaded on camera, as revenge for the rape and murder (though it is unclear if these insurgents knew that the kidnapped soldier was directly involved). The highest ranking soldier of the unit reports the incident, at which point his account is suppressed and distorted — this is where the “redaction” by the government occurs.

The film’s harshest judgment seems reserved for the solider making the video diary, who goes along with the others who commit the rape and murders (the girl’s family is also killed) to document the event like a journalist. Journalists often espouse an “ethics” of non-involvement, in which they act as passive observers and do not act affirmatively to assist their subjects. De Palma is puts that position up for debate. The other perspective is that maybe journalists act as collaborators and enablers. This other point of view has long been espoused outside of mainstream journalism. Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman’s book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media is perhaps the most well-known formulation..

De Palma’s film was a failure, in the sense that it did not raise awareness of the issues it presents. And yet, history has absolutely vindicated the film’s perspective. The Wikileaks organization released a trove of documents about the Iraq war and occupation that contradicted official claims and denials, most famously the “Collateral Murder” video, with an extensive campaign against the leaker Chelsea (Bradley) Manning and the operator of Wikileaks, Julian Assange. As this review is being written, hired mercenaries who worked in Iraq were just convicted for the Nissour Square Massacre. Another recent story showed that weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) were found in Iraq, but they were old ones leftover from the war with Iran in the 1980s, and had been made with U.S. assistance. With this information in hand, De Palma’s film looks like a chillingly accurate portrayal of what can be expected to happen in a military occupation, and how those at the bottom deal with those realities. This film deserves much credit for extending its moral concern not just to U.S. soldiers but also to the locals subject to the U.S. military’s use of force.

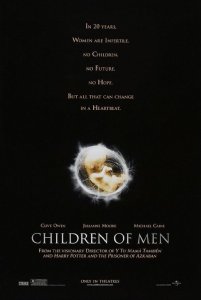

Children of Men

Children of Men (2006)

Universal Pictures

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

Main Cast: Clive Owen, Clare-Hope Ashitey, Michael Caine, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Julianne Moore, Pam Ferris

An adaptation of the P.D. James novel The Children of Men (1992), deals with a dystopian near future period in which humans as a species have become infertile. The film makes heavy use of symbolism, metaphor, and incorporates references to broadly contemporary political situations. Theo (Clive Owen), an unassuming nobody, is pulled into a conflict by a “terrorist” group “The Fishes”, who are fighting against a fascistic government in England. The youngest person in the world has just died. But Theo’s former wife/girlfriend Julian (Julianne Moore), who is a leader of sorts in The Fishes, has come to the know Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), the first woman to become pregnant in 18 years. The goal is to get Kee (like “Key”, get it?) and her child to “The Human Project,” a mysterious group supposedly starting a remote colony away from fascistic England. Theo is a broke hack, grudgingly helping the “terrorists” in exchange for payment. But as he interacts with these terrorists, he is revealed as an apostate activist, tormented by the death of his child years ago, who can’t help but to do the right thing no matter what danger that puts him in.

In an sort of thematic archtype, The Fishes betray their revolutionary intent to internal power struggles of the individuals involved. Theo and Kee, plus a midwife (Pam Ferris), narrowly escape The Fishes with the assistance of Theo’s elderly hippie friend Jasper (Michael Caine). The plan is to rendezvous with The Human Project on their hospital boat via a refugee camp — what looks like a concentration camp for all intents and purposes. Entering the refugee camp, full of “fugees”, the film depicts immanently contemporary horrors, with hooded prisoners subjected to torture, humiliation and execution. The scenes recall Abu Ghraib. On the way there, scenery of belching pollution coming out of drain pipes and foul gasses emanating from smokestacks implies total environmental collapse as a possible cause for the infertility problem. Inside the camp, Kee has her baby — will she name it Frolle or Bazooka? — and an insurrection breaks out between The Fishes and government troops. Brutally realistic scenes of urban combat follow. Theo and Kee try to reach a rowboat hidden in the camp. They have the assistance of a surprisingly benevolent ersatz hotel operator who doesn’t speak their language.

No doubt, the film has leftist leanings. The struggle for power in “civil society” creates conflict, while in the primitive setting of the refugee camp, there are benevolent humans. This could almost come from something Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote during the Enlightenment. But the quest to reach The Human Project seems like a step towards something else, something not quite of the Enlightenment. Going to a colony somewhere out in the sea seems like a rootless new beginning. The centrality of “fugees” — Kee is one — seems like a rejection of “identity politics” and an assertion that the future–the Human Project’s boat is called “Tomorrow” — must reject a retrenchment of uniformity, exemplified by the fascist English government’s use of concentration camps, and float about on something much looser, something that permits radically disparate elements to coexist. The common denominators are care for others, generosity, self-sacrifice. The film is a curiously uplifting message in a world that seems hopelessly and intractably locked into a downward spiral. What superficially seems like a dumb sci-fi thriller is actually quite an excellent movie, made all the better by uniformly superb acting and the highest technical proficiency. Hollywood is capable of something good now and again.

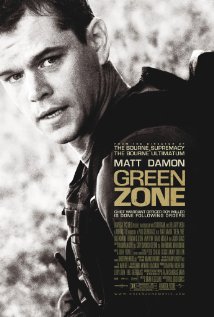

Green Zone

Green Zone (2010)

Universal Pictures

Director: Paul Greengrass

Main Cast: Matt Damon, Greg Kinnear

Some movies about the Unites States’ second war against former ally Iraq focus exclusively on the bravery, hardships, misfortunes, valor, and other personal experiences of the soldiers. Examples are The Hurt Locker (2008) and Stop-Loss (2008). These sorts of films make no attempt whatsoever to contextualize the war. In The Hurt Locker, the main characters diffuse improvised explosive devices throughout the entire movie. Why are those bombs being made and planted in the first place? The movie doesn’t even entertain that question.

Green Zone falls into another category of films that try to explain what the war was about. Another example in this category is Redacted (2007). Green Zone is loosely inspired by journalist Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s book Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone (2006), which provided an account of the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) that the U.S. government installed in a heavily fortified city-within-a-city in Baghdad during the war (until June 2004, when the Green Zone was handed over to the U.S. State Department). The script for Green Zone, however, is fictional. Paul Bremer, the incompetent neo-con and Henry Kissinger protégé in charge of the CPA (after Lieutenant General Jay Garner was abruptly fired) is fictionalized as Clark Poundstone (Greg Kinnear). Chief Warrant Office Roy Miller (Matt Damon) is an outrageously superhero-like soldier who seeks the truth about the war, when his missions to secure materials for weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) turn up nothing and he suspects bad intelligence.

The plot is far-fetched, and the timeline historically inaccurate. Still, the movie has somewhat decent intentions. Drawing from Chandrasekaran’s book are the major points that Bremer & Co.’s decisions to implement #1 De-Ba’athification (removal of all government officials from Saddam Hussein’s socialist party) and #2 dissolution of the Iraqi Army were monumentally bad decisions, and the idea that the folks in the Green Zone calling the shots lived in a bubble divorced entirely from the facts on the ground outside the well-protected green zone perimeter. Even in 2014, a decade later, Bremer continues to defend what he did, going so far as to call dissolution of the Iraqi army the best decision he made with the CPA (Losing Iraq). The movie positions the CIA agent Martin “Marty” Brown (Brendan Gleeson) as a counterpoint figure. There, the script admirably tries to portray the U.S. government not as a monolithic entity, but subject to competing factions within it, complete with individuals vying for personal advancement and inter-agency turf battles. There are also heavy-handed attempts to provide an Iraqi perspective, mostly by way of a former Iraqi soldier nicknamed “Freddy” (Khalid Abdalla). But in spite of those attempts, the plot lurches from one action movie cliché to the next.

Director Paul Greengrass also directed Damon in two Bourne movies, and there are a few too many parallels here for comfort. There are extended chase scenes filmed with shaky portable cameras and Damon’s character always seems to be a step ahead in ways that strain credibility. Also, Kinnear has a lackey in the army who unflinchingly carries out orders, even when those include taking out fellow U.S. soldiers. That is possible, but these soldiers are portrayed as one-dimensional robots, as if Damon’s character is the only soldier in the army with a conscience. These features create plot situations that clearly lack authenticity. The tone is frequently of Damon’s character as a truth-machine, pitted against a monster in Kinnear. This is a little too simple. Chandrasekaran portrayed the CPA as a corrupt organization that placed loyalty to George W. Bush and his GOP party above actual qualifications or good decision-making. The later book by Peter Van Buren, We Meant Well (2011), which focused on the U.S. State Department’s bungled, ridiculous efforts at “reconstruction” of Iraq in 2009-10, demonstrates how that same mindset also took hold in the State Department. It wasn’t a “few bad apples”, it was a spectacle of an immensely and widely corrupt U.S. government trying to “liberate” Iraq from its corrupt government that hardly seemed any different!

This film deserves credit for trying to imbue a Hollywood movie with a realistic perspective of what happened to cause the Iraq war to proceed as it did. But it also deserves derision for being contrived and implausible, a failure of technique and writing mostly, which directly undermines all attempts to paint an accurate picture of the war.