Mamma Roma (1962)

Cineriz

Director: Pier Paolo Pasolini

Main Cast: Anna Magnani, Ettore Garofolo

It is common to look at Pier Paolo Pasolini as a Marxist, but that is inaccurate, or at least, it presents an incomplete picture. What Pasolini took from Marx was a view of class relations. That is the focus of his second feature as a director, Mamma Roma. His directorial debut, Accatone (1961), was a story of a pimp and other people around him at the fringes of Italian society, told in a way that made him an anti-hero. It drew on the sort of perspective that Jean Genet had developed in writings like Journal du voleur (1949), making an existential transposition of the ideologies of virtue and fulfillment of dominant society to those of vagrancy, theft, and prostitution. Pasolini, like Genet, made his characters, who by accepted standards were the lowest of low, come across to the audience as sympathetic. They strove in different ways than “respectable” society, but they struggled and strove nonetheless.

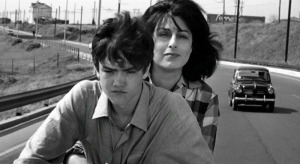

Mama Roma is the story of a former prostitute (Anna Magnani) whose now former pimp is getting married. She plans to move from the rural backwaters of Italy to Rome and open a fruit stand. In doing this, she reclaims her 18-year-old son (Ettore Garofolo) to live with her for the first time. This involves something like a Beverly Hillbillies scenario. Mama Roma wants to take on a different social position, and to renounce and conceal where she came from. She comments in the film about how what she did in the past was to make possible her future, for her and her son. Mama Roma tries to win her son Ettore’s affections. She buys him a motorcycle. While they have a fun ride together, it is only at the level of consumer materialism that she can relate to her son. He ultimately finds material possessions unfulfilling. Ettore lacks the particular social ambition of his mother, and harbors some resentment that his mother has transplanted him to a city in which he is forced to take on new roles, such as work that does not interest him. Numerous incidents occur in which he tries to prove his worth to local ruffians and a girl. This includes a brazenly ill-advised attempted robbery that lands him in jail, at which point an illness takes his life. In the throes of illness, he repents, in a way, by reaffirming that he is who he is, and should not force himself into the expectations of a social strata that is not his own. The film ends with Ettore strapped to a table by his jailers, dying with his arms out, implying a crucifixion.

It is clear that Pasolini sees Ettore as the moral center of the film. He, eventually, takes on what the philosopher Parmenides called the “way of truth”. Mama Roma’s attempts to take on a new social position, in crummy high-rise apartments, are a betrayal of her rural roots. She follows what Parmenides called the “way of appearance”. This is portrayed in numerous scenes in which to take control of situations, or to avoid conflict, she lapses back to her old ways. In spite of her aspirations, the real Mama Roma is the part of her she denies. Ettore is pressured to have ambitions, and it is only when thrust into the milieu of city life that he finds himself in despair and ashamed of his roots. He rediscovers this by the end of the film, but only when his mortality catches up to him.

The script of this film is excellent. It explores the social field almost like a sociologist. There is much focus on the idea of social trajectory and momentum, and a rejection of those things at a fundamental level by insisting instead on a kind of radical egalitarianism of singular, unitary social standing. The film as a whole, though, is something of a failure. Pasolini was still in his early phase as a director. The influence of neo-realism is still strong. But the main problem is that the acting is inauthentic. Pasolini admitted that Anna Magnani was miscast, because she had never lived a subproletarian existence (her habitus was that of semi-autonomous peasantry and small-scale merchants, who emulate and reflect the lifestyles of of capitalists and the upper middle class). Magnani was not someone from the rural poor, and therefore she did not know that life. Pasolini had this to say in an interview:

“Well I’m rather proud of not making mistakes about the people I choose for my films . . . . The only mistake I’ve made is with this one with Anna Magnani — though the mistake is not really because she is a professional actress. The fact is, if I’d got Anna Magnani to do a real petit bourgeois I would probably have got a good performance out of her; but the trouble is that I didn’t get her to do that, I got her to do a woman of the people with petit bourgeois aspirations, and Anna Magnani just isn’t like that. As I choose actors for what they are and not for what they pretend to be, I made a mistake about what the character really was, and although Anna Magnani made a moving effort to do what I asked of her, the character simply did not emerge. I wanted to bring out the ambiguity of subproletarian life with a petit bourgeois superstructure. This didn’t come out, because Anna Magnani is a woman who was born and has lived as a petit bourgeois and then as an actress and so hasn’t got those characteristics.” Pasolini on Pasolini (1969)

While Mama Roma is engaging in concept, it also is less successful on its own terms than other Pasolini films. Accatone, for one, provides a more fluid verisimilitude. Mama Roma is something of a sequel, and suffers from all the limitations that such a label implies. The bawdy, direct humor of Pasolini’s later films is not yet present either, nor the intellectual commentary in his repurposing of classics. This is not one of Pasolini’s best films, but even Pasolini on an off day is something.