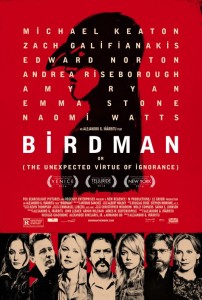

Birdman: or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014)

Fox Searchlight

Director: Alejandro González Iñárritu

Main Cast: Michael Keaton, Edward Norton, Emma Stone, Zach Galifianakis, Naomi Watts

Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous: Actors Edition.

Birdman is a film that wants to be deep. It concerns an aging actor Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton), whose career has become defined by a title role in a superhero movie franchise. But now he is organizing (as writer, director and actor) a stage adaptation of the Raymond Carver short story collection What We Talk About When We Talk About Love on Broadway. Unhappy and frazzled, he brings in a well-known stage actor Mike Shiner (Edward Norton) as a replacement for one of the male stars. His daughter (Emma Stone), back from drug rehab, is “assisting” him as a way to keep her occupied. The film builds on intense scenes with long shots, set in the bowels of the theater, on the stage, and in the dressing rooms. Intermittently through the film, Michael Keaton’s character hears a voice in his head, and he seems to possess the ability to fly, move objects with his mind, and otherwise really be a superhero — or is this just a psychotic break brought on by the stress of the theater production?

The early part of the film sets up the conflicts, between the actors in the Carver adaptation and between Riggan Thomson and his legacy. Mike Shiner is a talented actor who we are to believe exists in two diametrically opposed realms: that of the “real world” where he is despised, impotent and rejected, and that of the stage, where he is adept, creative and appreciated. To impress the importance of Acting and the Theater, his character, and the others, behave badly and obnoxiously, parading about naked, smashing things in bars, and engaging in public arguments and fights. The main characters storm about the building, often met with bewilderment by the theater’s staff and technicians. Yet the staff and onlookers seem powerless to engage any of this. They are onlookers, not able to play a role in the tribulations of the Great Artists. The last half of the film sets out the resolution of those early conflicts. Michael Keaton gets most of the screen time toward the end. The ending, as we’ll see, feigns ambiguity.

The fatal flaw of this film, except for pretensions to depth that it doesn’t earn, is that it relies on a con. While Riggan Thomson seems to want to make deep art not just commercial movies, the Thomson character is always obsessed with status and power. He has a lot of money (financial capital), which, by personally putting up considerable funding for his play, he attempts to trade for greater recognition as an artist (cultural capital). In this, the theater is somehow seen as loftier in a hierarchy of arts, the audience of Broadway plays deemed more significant than the (presumably) middle-American moviegoers (and Times Square tourists) who liked Thomson’s turn as Birdman in the movie franchise. During a run-in with a theater critic in a bar, who calls out Thomson for his attempt to convert his movie celebrity into a different kind of cultural status on Broadway — and rather implausibly states in direct terms her role as a guardian of middlebrow tastes who must oppose such conversions of social capital — he angrily proclaims what a risk he’s taking. As the audience, we are to forget that this risk is just a gamble, like any other in (casino) capitalism, from a player who simply started the game with more chips than the others. The critic says her complaint is that Thomson is taking up theater space that could be put to better use (we are to infer she means someone with pre-existing cultural capital in the New York City theater scene), and promises to destroy the play with a scathing review, confident that she alone holds the power to do this (something the film undercuts, given the insatiable craving that fans seem to have to see Thomson in, well, anything).

There is another, earlier scene in which the daughter excoriates Thomson for failing to understand his insignificance — apparently unaware that this is the set-up for an old joke. That scene sits almost in isolation for a time, until the final scenes of the film provide a rebuttal. By the end, we hear that the voice in Thomson’s head (it is the Birdman character) explains the truth to him, and on the question of whether he is a superhero or a psychotic, his daughter in the final scene appears pleasantly surprised that rather than committing suicide by jumping out a window, he might really be flying. Rather than convince her father of his insignificance, instead it is her who ends up convinced of his exceptionalism. She also instructs him about online social media — making a fool of oneself publicly is the new way to wield power over a fan base. He just needed to understand contemporary marketing tactics a little better, see? Other scenes in which tense family relations come up, seem to be resolved through professional prestige: if Thomson’s play succeeds commercially or critically (does this film see any distinction between the two, really?), then all his other problems are solved.

The film ends on a note seemingly lifted from the iconic Jimmy Stewart family film Harvey (1950), about an alcoholic man whose best friend is a giant rabbit who may or may not be a figment of his imagination. Yet there is none of the heart or sweetness of the Stewart film here. Yes, there is good acting, but the scenes in which the acting is prominently on display are constructed for maximum intensity — with long shot after long shot, many close ups and hand-held camerawork — all meant to focus attention on isolated emotional outbursts strung together in series. While Harvey might be dismissed as a naïve children’s film, it opens the possibility for different ways of looking at the world, in a way in which, from the standpoint of social status, Stewart’s character stands to gain nothing at all from his friendship with a giant (imaginary?) rabbit. In Birdman, Michal Keaton’s character simply looks for the most effective path toward the fame and fortune he desires. There is no question about the path he’s following. He just needs to out-compete the other actors out there in the mean world of professional theater. How?

Birdman suggests that there is Truth. It is masked. But the voice in Riggan Thomson’s head still tells him the something that guarantees his happiness. This is the religious/theocratic core of the script. Thomson succeeds or fails based on whether he recognizes this Truth sufficiently. What we are left with is an apology for fame and status seeking, justified by reference to some higher power that only the exceptional few can access. Left somewhat unspoken in Birdman is how Riggan Thomson came to be a major Hollywood actor. There is a trite story of Raymond Carver congratulating him as a child, convincing him to pursue acting as a career. But it takes much more than talent and desire to succeed in the world. Only people with certain social capital can pursue careers in the arts, often having family legacies in that industry, having wealth that allows for unproductive time spent on artistic interests. So, there is also a hidden fatalism in this film. Thomson is destined to a path, he only needs to believe in it enough. So, to paraphrase Bertolt Brecht from Geschichten vom Herrn Keuner, Riggan Thomson wonders maybe if there is a god, but in his wondering he already decided, and it seems he needs a god, because he would not act in such a way to achieve fame and riches if he could grasp any other way than what those fame and riches seem to guarantee for him in the world. So no existential angst for him. He is absolved of creating meaning for himself. He just listens to the voice in his head. This, supposedly, is the “unexpected virtue of ignorance.” Strangely, it seems lacking in virtue. Greed is good?