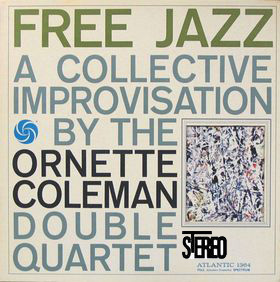

The Ornette Coleman Double Quartet – Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation Atlantic SD-1364 (1961)

“It is an insight of speculative philosophy that Freedom is the sole truth of Spirit.” – Hegel, Reason in History

There is much confusion over what “free jazz” means and what Ornette Coleman’s album of the same name really means. There is a Paul Bley interview (The Wire, Sept. 2007) that I cite as much as possible that explains much about Ornette Coleman’s role in this debate. But let’s step back a bit further. If “free jazz” means totally spontaneous improvising, then it long predates Ornette or the 20th Century. Cavemen banging on logs with sticks were playing free jazz by that definition. Obviously, this is not what people really mean, or, if they do, their point is trivial. Rather, as Bley explains, Ornette’s approach was to tear down barriers and instead construct his own musical system instead. Basically, this is the sort of political project that goes back quite a ways, exemplified by Age of Enlightenment thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau (whose social contract theory posited that groups invested authority in themselves). There were also certainly other people working in this direction just within the realm of jazz music in the 1950s and even late 1940s (Cecil Taylor, Lennie Tristano, Stan Kenton), though Ornette did more than most to convey a sense of an identifiable and lasting new system of performance, rather than merely tearing down the old systems for a kind of one-off experiment. The importance of “free jazz” as a “genre” is that it is positioned within a very particular time, place and social structure, and gains meaning primarily in relation to those contextual reference points, including the history of atonal music in the Euro-classical tradition. This was near the end of the Jim Crow era, thinking well beyond its limits to questions of the ways people would relate to each other beyond such systems of institutionalized discrimination.

G.D.H. Cole wrote and introduction to The Social Contract and Discourses of Rousseau. In that introduction (pp. xxvii-xxxvi), he wrote about different types of social contract theories of politics, and contrasted the views of Thomas Hobbes with those of Rousseau.

“All Social Contract theories that are at all clearly defined fall under one or other of two heads. They represent society as based on an original contract, either between the people and the government, or between all the individuals composing the State. Historically, Social Contract theories tended to pass from the first to the second of these forms.

***

“Hobbes agreed that the original contract was one between all the individuals composing the State, and that the government was no party to it; but he regarded the people as agreeing, not simply to form a State, but in one and the same act to invest a certain person or certain persons with the government of it. He agreed that the people was the final source of all authority, but regarded the people as alienating its Sovereignty by the contract itself and as delegating its powers, wholly and for ever, to the government which its members agreed to set up. As soon, therefore, as the State is established, the government becomes for Hobbes the Sovereign; there is no further question of popular Sovereignty but only of passive obedience: the people is bound, by the contract, to obey its ruler, no matter whether he governs well or ill. It has alienated its rights to the Sovereign, who is, therefore, absolute master.

***

“Not until we come to Rousseau is the second form of the contract theory developed into a thorough-going assertion of democratic rights.

***

“Philosophically, Rousseau’s doctrine finds its expression in the view that the State is based not on any original convention, not on any determinate power, but on the living and sustaining will of its members.

***

“Pure democracy, however, meaning the government of the State by all the people in every detail, is not, as Rousseau says, a possible human institution. All governments are really mixed in character; and what we call democratic governments are only comparatively democratic. Government will always be to some extent in the hands of selected persons. Sovereignty, on the other hand, is in Rousseau’s view absolute, unalienable, and indivisible.”

Perhaps that is a rather long explanation, but it makes for a useful analogy here. The features of bebop (and hard bop and cool jazz) resemble in certain respects a Hobbesist view. The players of that style/genre invest in a set of governing rules, and perhaps a set of pioneers who establish those rules (Charlie Parker, etc.); all those players then follow those rules and surrender their ability to change the rules. Maybe this is an oversimplification, but when Ornette Coleman came along he very clearly marked a transition toward a Rousseauian conception of jazz. Suddenly, all the players in a combo could have a say in making the rules. Sure, they ceded some organizational authority to Ornette as the bandleader and composer to put forward some elements of the music on their behalf, but there was no privilege in that that could not be withdrawn at any time (even during performance). The very structure of the music was always open to the will of all the band members (to a point at least; for a discussion of limits on that approach see Jo Freeman‘s classic essay, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness” which is a more recent and nuanced version of a set of arguments that runs from Robert Michel‘s reactionary tract Political Parties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy).

Rousseau himself once wrote:

“In our day, now that more subtle study and a more refined taste have reduced the art of pleasing to a system, there prevails in modern manners a servile and deceptive conformity; so that one would think every mind had been cast in the same mold. Politeness requires this thing; decorum that; ceremony has its forms, and fashion its laws, and these we must always follow, never the promptings of our own nature” A Discourse on the Moral Effects of the Arts and Sciences (1750).

These “promptings of our own nature” are precisely what Ornette and his band offer up on this album. And to do so requires an impolite, impertinent break from servile conformity.

The music of Free Jazz features a “double quartet” (so named rather than just an octet because it was Ornette’s regular quartet plus other musicians, including a former drummer of his regular quartet, who doubled up on various instruments with the original quartet — some of the double quartet performers had recorded together the day before on John Lewis Presents Contemporary Music 1: Jazz Abstractions: Compositions by Gunther Schuller & Jim Hall). They play themes and variations. In other words, a theme is stated, then variations on the theme are played. The variations are not limited by strict tonality or chord changes. The themes are sometimes described as “buzzing fanfares”. To some, this is odd, dense, difficult music. To others, this can be fun, enjoyable stuff. There are also opposing views about this being formless, messy, insignificant music, and even some say that the use of a theme/variation approach makes this not free jazz at all (a bit of hindsight thinking there). It is possible to ask about critics who think this is formless whether they are socially conservative or reactionary. Perhaps they don’t admit it, but do they pine for a sense of “order” or “sensible limits” that just so happen to depend on certain groups having power over others, that reject the idea that people can set rules for themselves and instead believe that only certain people (or even deities, if we include here the lunatic royalist/theocratic fringe) are capable of establishing rules that all others must obediently follow. If all this seems removed from the music of Free Jazz, it shouldn’t. Listeners do tend to split along these very lines, and therefore this is about something inherent in the music.

The album itself is just one long track (spanning two sides of the original LP). There was another song recorded, “First Take,” which was released on the archival collection Twins (1971) and then later appended to reissues of Free Jazz as a bonus track. John Coltrane was heavily influenced by Ornette — he took private tutoring from Ornette for a while. This album inspired Coltrane to record Ascension. So if this album is to your linking, perhaps that is another recording worthy of a listen.

Coleman plays well. His performance is somewhat typical of this period. Eric Dolphy appears on bass clarinet. If there is any other jazz musician that needs to be considered alongside Ornette it has to be Dolphy. A talented multi-instrumentalist, he played with a very “vocal” quality and often leaped between registers. His phrasing was more atonal than Ornette’s. The bass clarinet, with its woody sound, it a good compliment to Ornette’s brash and sour tone on alto sax, and it manages to cut through the sound of seven other players well. Dolphy was one of the few performers worthy of keeping up with Ornette in a setting like this. Yet he never hogs the spotlight. Ed Blackwell is a crucial piece of the puzzle too. Billy Higgins plays somewhat conventional cymbal rides, while Blackwell moves around his drum set, and plays his toms more frequently, adding hints lyricism to his drumming. Bands with two drummers often drift into a morass of indistinct bashing around, but here the two percussionists are able to both provide a sense of forward propulsion through a steady beat and range through rhythmic improvisations — many modern jazz groups in the coming years tended to choose only one or the other. They get some solo time near the end of the performance. Charlie Haden is the most prominent of the two bassist. Scott LaFaro is here too, and he would replace Haden in Ornette’s regular combo until his death in 1961. The bassist get some solo time as the horns drop out roughly two-thirds to three-quarters into the performance. The two trumpet players are Don Cherry and Freddie Hubbard. They are very different players, with Hubbard playing more conventionally melodically. The contrasts that the brass players contribute is another key ingredient in making the music distinctive.

The original album jacket featured a painting (White Light) by abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock, who painted using “loaded brushes” and drips. There is a story about Pollock (possibly true) that an unsympathetic critic came to see him paint at his studio. Fed up, Pollock flung a gob of paint across the room and precisely onto the doorknob, telling the visitor: there’s the door. He both rebuked the critic and demonstrated his precision (which the critic denied) with that single gesture. Ornette was less brash and far more soft-spoken. And yet, he faced many of the same criticisms as Pollock and used similar artistic techniques. Visiting a Pollock exhibit, Ornette once said,

“See? There’s the top of the painting, there’s the bottom. But as far as the activity going on all over, it’s equal. It’s not random. He knows what he’s doing. He knows when he’s finished. But still, it’s free-form.”

Sometimes unacknowledged is that Pollock was interests in jazz, especially be-bop. There was a definite affinity between his painting and jazz music. Ornette obviously saw parallels.

Listeners who say Ornette was not really playing “free jazz” because others had less structure miss something. Being more chaotic, with less delegation of organization, is merely a matter of degree. The fundamental character of self-determination, along the lines of Rousseau, is the major break that Ornette Coleman represented within music (and jazz music especially). And more so, Rousseau rejected the idea of total direct democracy as impractical, and Ornette likewise tended to reject the idea of complete unstructured, chaotic total improvisation. The music does reject a center, tonal or social, and for that reason is anti-essentialist (there is no “essence” or “core” of the music or its performers). Instead the music focuses on what the performers do.

There is another criticism of all “free jazz” that it is elitist. This is a thorny issue. On the one hand, it was music that was never widely popular, and its main audiences tended to be educated, well-off urbanites. But, on the other hand, given how this music fits so well with the sorts of political theories that have been considered dangerous to social and political elites since the beginning (Rousseau had to flee his home under threat of death due to his writings; The Communist Manifesto is just a refinement of Rousseau’s concepts), this would seem like the very opposite of elitist music. Could it be that those who see this as elitist music simply assume that ordinary people are incapable of changing their views, to adapt to a new kind of music, which is almost like saying they are inherently conservative? Or like saying they are inherently stupid?

Free Jazz is one of those albums that some listeners will immediately like, even just upon hearing about the concept and the title. This is the sort of music that has the capacity to change a listener’s entire conception of what is possible in music. On the other hand, there are and will continue to be detractors. But even those who don’t immediately like this, or consider listening to it to be hard work, should at least give it a try, if for no other reason that to gain some exposure to the pioneering conception of music that gave rise to it in the first place — a musical education without something like Free Jazz will necessarily be incomplete.