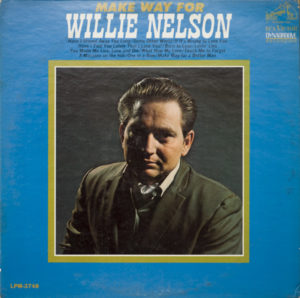

Willie Nelson – Make Way for Willie Nelson RCA Victor LPM-3748 (1967)

Here’s a rather forgotten early Willie Nelson LP that is actually among his better early albums, relatively speaking. Recorded in Nashville, this teamed Willie with producer Felton Jarvis after RCA Records’ main producer Chet Atkins was too busy to handle the recording sessions. This proves to be a boon for the recordings, by sparing them from Atkins’ unsympathetic production style and its usual cloying bourgeois and petite-bourgeois aspirations evident on the same year’s The Party’s Over (And Other Great Willie Nelson Songs), for instance. This is an album recorded much the same way as Country Willie — His Own Songs (1965), another decent early Willie Nelson album. There is only one of Nelson’s own compositions here. These are mostly cover songs. This album can still be described as having the Nashville sound, but it retains a honky tonk influence. Nelson would return to honky tonk on and off again for his entire career. The opening “Make Way for a Better Man” is good, with understated backing orchestration. Other songs like “Have I Stayed Away Too Long?” are decent too, even though the guitar and vocals sometimes sink into a leaden rhythm. There are signs that there was perhaps insufficient rehearsal, and some of these recordings might be first takes. But even if the recordings seem relatively raw at times, that actually suits Willie’s style of singing — actually being crucial to the success of later albums like Yesterday’s Wine and Phases and Stages. There are some odd song choices here, like the 1960s pop staple “What Now My Love [“Et maintenant”]” (even The Temptations released a version of the song in ’67). Willie’s own “One in a Row” is also one of his lesser compositions — recorded here in the same ornate style as “What Now My Love.” On the whole, this holds up well enough all the way through. It isn’t a great album, and it certainly doesn’t do much to distinguish itself from other country albums of the day, but it has a sort of charm in its predictability and familiar approach. As for this album being mostly forgotten, at this writing, the album is not even listed in the Musicbrainz database and there is no track listing in the RateYourMusic database; there is also no review on AllMusic or on RateYourMusic. It was, however, one of his more commercially successful albums at the time, peaking higher on the country music “charts” than any of his other pre-Red Headed Stranger albums.