MF DOOM – Operation: Doomsday. Fondle ’em FE-86-CD (1999)

MF DOOM (born Daniel Dumile) is an English born rapper who got his start in the music business under the name Zev Love X in the hip-hop group KMD. But his brother and bandmate Subroc was killed in a car accident and — at the same time — the band was dropped by its label. KMD disbanded. After working open-mics and the like, Dumile re-emerged as a solo act under the MF DOOM name. His solo debut album was Operation: Doomsday.

His type of hip-hop zigged while commercial hip-hop zagged. Some call this “backpack rap”, in reference to its appeal to music nerds listening with headphones on trains and buses (while wearing a backpack) — not the sort of music intended for dancefloor play “in da club”. It was a resolutely indie/underground phenomenon initially, but eventually rose to prominence through the likes of Kanye West. MF DOOM achieved great success himself years later with his collaboration with Madlib, Madvillainy.

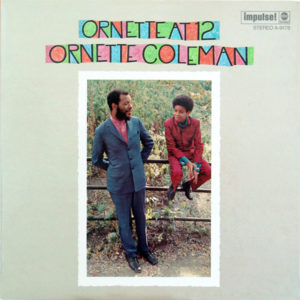

The samples used on the album draw heavily from late 70s jazz fusion and smooth R&B, through 80s smooth jazz. There is also extensive use of superhero cartoon samples. The MF DOOM character is based on the “Dr. Doom” character from Marvel comics, and there are many samples related to that character woven through the album in a series of skits. The musical sources for the samples represented — mostly — passé stuff among the audiences listening to hip-hop at the time. Though the superhero cartoon references were semi-established via the Wu-Tang Clan, particularly Ghostface Killah‘s persistent use of samples related to Mavel’s Iron Man character in his solo recordings around the same time. DOOM’s rapping tends toward long, dense verses delivered with a kind of lackadaisical drawl. In concert, he later took to wearing a metal mask based on a prop from the movie Gladiator (2000), released the year after Operation: Doomsday. He had already performed in more improvised masks leading up to the release of his debut album.

A useful reference point, from outside hip-hop, is Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti. Both draw from the music of their youth, especially the leftovers of media of the past that have lost most of the symbolic representation of cultural sophistication they once carried. But the similarities largely end there. While Pink uses a reverent/irreverent approach, MF DOOM instead builds a kind of protective cocoon of wounded cynicism. He hides behind a mask and pseudonym, drawing from childhood cartoons/comics to construct a supervillain character. As many have noted, this might be seen as a self-defense mechanism after Dumile’s personal traumas of the early/mid-1990s. It also tends to close off and protect its innocence from corrosive outside forces of the adult world. The invocation of a supervillain character rather than a superhero one is a slight twist. But it is still a variation on the sort of worldview the writer Jean Genet expressed in Journal du voleur [The Thief’s Journal]: “Repudiating the virtues of your world, criminals hopelessly agree to organize a forbidden universe. They agree to live in it. The air there is nauseating: they can breathe it.” Of course, at its extreme, this is a similar strategy to one that “hoarders” use in response to personal trauma.

Harmony Korine‘s film Mister Lonely (2008) is more or less an attempt to analyze precisely the same thinking that drives Operation: Doomsday. In that film, the main characters are celebrity impersonators who are unable or unwilling to live under their own identities, instead forming a commune. Eventually, after circumstances cause the commune to fall apart, the protagonist sheds his costume and assumed identity and lives as himself. There is something to the notion that the pressures of modern society to be an individual (and “personal brand”) are too great, especially for the most vulnerable and the traumatized. But, still, there is a problem with the lack of a strategy to ever step out from behind an assumed identity. There is never any hint of how that might happen on Operation: Doomsday. This music seems to stop at presenting a defense mechanism.

At a time when hip-hop’s growing commercial dominance was causing the music to stagnate somewhat, Operation: Doomsday. came out of left field. For instance, OutKast was considered by many hip-hop heads to represent something new and different, even as that group was (in the late 1990s at least) offering only a slight variation on the glorification of the same money-obsessed, misogynistic “playa” personas that were still commercially dominant. MF DOOM, on the other hand, suggested there was a whole lot more possible, much further afield from the mainstream. Sure, groups like Hieroglyphics already had a small following along these lines, but it was after Operation: Doomsday. found surprising success (even if only coincidentally) that momentum carried forward with the Anticon collective, the Project Blowed collective, Antipop Consortium, Kanye, and more.

And it probably has helped MF DOOM’s commercial success that Hollywood became absolutely fixated on making one big-budget superhero movie after another after Operation: Doomsday. was released — a trend that took off more or less immediately after the release of this album. While certainly there is no direct connection between MF DOOM’s appropriation of comic book characters (or Ghostface’s, etc.) and Hollywood’s economic priorities, they both fit together in the same social context of neoliberal hyper-individualism.

When this album came out my roommate at the time was very into it, though I was more ambivalent. I probably like it more now than back then, though I think DOOM did better later. It does have its drawbacks, namely a few songs that overstay their welcome with gimmicks stretched out too long. From a production and beats standpoint, Take Me to Your Leader (under another pseudonym King Geedorah) is better. From a lyrics and straight rapping standpoint, Vaudeville Villain (under yet another pseduonym Viktor Vaughn) is better. Overall, even the later effort under the MF DOOM name Mm..Food is a bit better. Though this solo debut is still strong.

The album has been reissued numerous times. One deluxe edition comes in a collectible lunchbox, complete with trading cards and a bonus disc with 12″ and instrumental versions of various songs. Another reissue includes the bonus disc but omits the non-musical extras like the lunchbox. The bonus disc is fine, but hardly essential. Reissues have replaced the original cover artwork (by Lord Scotch 79th) due to unspecified licensing issues. The lunchbox reissue instead uses artwork (by Jason Jagel) that vaguely resembles the original, but the other bonus disc reissue has cover artwork (also by Jason Jagel) that parodies Paul Robeson‘s Songs of Free Men.