Link to an article by William Blum:

Month: September 2017

Variety Shows Then and Now

It recently occurred to me—while watching a Muppets movie—that there is a noticeable different between television variety shows from the time when The Muppet Show was on TV and today. Back then, variety shows with song, dance and miscellaneous acts tended to have a stable company performing regularly, and drew in guest performers. Sometimes the guests were “new” potential stars, being “introduced” through the show, but as much or more often they were established professional entertainers of some sort. Today, in marked contrast, the traditional “variety” shows (and specials) are mostly gone, but in their place are “reality” shows framed around competitions. These are sometimes exclusively singing or dance oriented, or might be open to a variety of “talent show” acts beyond just song and dance. These new shows often have judges, either supposed industry “experts” or entertainment celebrities, who pass judgment on the competing acts. These differences between similar television shows of these eras actually matches up quite closely with the “market” logic of the present “neoliberal” era. Now, the shows have “elite” judges and a bunch of rabble competing for some sort of recognition or prize, their being too little reward allocated for all performers. There is no job security for the contestants, who have to compete against each other–the judges standing apart from that competition.

Thomas Ferguson, Jie Chen & Paul Jorgensen – Fifty Shades of Green

Link to a report by Thomas Ferguson, Jie Chen & Paul Jorgensen of the Roosevelt Institute:

“Fifty Shades of Green: High Finance, Political Money, and the U.S. Congress”

Bonus Links: Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money-Driven Political Systems and “Money Still Rules US Politics”

Tom Waits – Mule Variations | Review

Tom Waits – Mule Variations Anti- Records 86547-2 (1999)

Waits’ late-90s “comeback” album has aged well. After the achievement of Rain Dogs in the mid-80s, and Bone Machine in the early 90s, he largely slipped from view for a few years. His comeback positioned him as something of an elder statesman of the independent rock scene, which still had some vitality even as major labels had already started to consolidate their investments around a fairly narrow range of music that excluded stuff like this.

When David Bowie had mild resurgence a couple years prior with EART HL I NG, he seemed to draw his subject matter from watching movies on TV. Although Bowie and Waits go in much different directions in terms of genre, and only Waits leans on the use of humor, Waits’ lyrical focus has shifted to more middle-aged circumstances as well here too. Take “Come on Up to the House,” which might be viewed as one of the best rock songs about a dinner party. The lyrics, which cajole someone loaded with excuses to come over for a visit, have some great turns of phrases (like about coming down from that cross because we could use the wood). It also features orchestration that recalls the album-closing style of “Anywhere I Lay My Head” from Rain Dogs or, reaching back further, “Cripple Creek Ferry” from Neil Young‘s After the Gold Rush. As Harry Nilsson once did so well, “Cold Water” also evokes the mundane aspects of daily life, like taking a shower. And “What’s He Building?” is an eerie rock monologue in the tradition of The Velvet Underground‘s “Lady Godiva’s Operation” but with a neighborly suspicion narrative like that of the Tom Hanks film The ‘Burbs. Sure, Waits had released “In the Neighborhood” on Swordfishtrombones, but the irony of that song in muted if not absent here more than fifteen years later.

At the time the album came out, “Hold On” was the single, and it met with success. It hearkens back to the sentimental (and sometimes maudlin) side of Waits’ music—think “Tom Traubert’s Blues (Four Sheets to the Wind in Copenhagen)” from Small Change, “Ruby’s Arms” from Heartattack and Vine, and “time” or “Blind Love” from Rain Dogs. This is something that appears elsewhere on the album too. Yet this is a softened, more mature sentimentality that stops just short of being truly maudlin. These songs work well here. The opener “Big in Japan” also tended to be liked by audiences. It has a heavier beat and more rock and roll edge to it, with some gruff histrionics. While these are solid songs, the album as a whole has much more to offer. It is really the more mature, middle-aged attitude (Waits was nearly 50 years old when it was released) that shines through in hindsight. It lacks nothing in terms of relevance and appeal to listeners of all ages.

Maybe surprisingly, this is really one of the finest full-length albums of Waits’ entire career, all told. He continued to put out some decent music later on but despite some nice highlights it was not as consistently solid at album length.

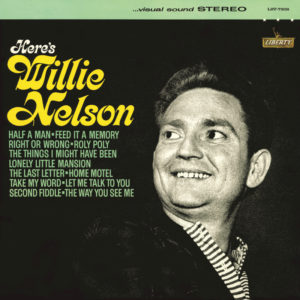

Willie Nelson – Here’s Willie Nelson

Willie Nelson – Here’s Willie Nelson Liberty LST-7308 (1963)

A common opinion is that Willie Nelson’s second full-length album Here’s Willie Nelson was a step back from his debut …And Then I Wrote. Those people often say that this is “Nashville cliché”, referring to the “countrypolitan” style it evinces. But a response to all that should be, “And?” Yes, Here’s Willie Nelson fits in the mold of the weepy drama of the “Nashville Sound” — a close comparison would be Skeeter Davis‘ “End of the World.” But it really represents the best possible execution of the Nashville Sound.

There are a couple of things that boost this album. First is producer Tommy Allsup. He was a touring member of The Crickets and once lost a coin flip to Ritchie Valens such that he lost a seat and was not on the plane that crashed near Clear Lake, Iowa on February 3, 1959 that killed Valens, Buddy Holly and The Big Bopper. Allsup brings out the best in the instrumental performances, accentuating the spark and energy of all the performers and balancing Willie’s vocals with the orchestration. He eschews the prominent focus on Nelson’s vocals evident on his debut. Surprisingly, pushing the vocals down a little in the mix works well.

Another key factor in the album’s success is the arranging work of Ernie Freeman and Jimmy Day. The orchestral treatments by Freeman are really quite excellent and much better than the formulaic leftovers that characterized Willie’s albums later in the decade for the RCA Victor label. Each song gets its own distinct character, matched to the tone of each song. Just check the calmly sizzling trills and glissandos from the strings on the bluesy closer “Home Motel,” and contrast the pastoral elegance and more complex harmonic blocking of “Half of Man” or the busy energy of the strings on “Take My Word,” or the juxtaposition of pedal steel guitar with sweeping string orchestration and indistinct backing vocal chorus of “Second Fiddle” where the orchestra briefly trades off with a solitary country fiddle solo and closes with a country/Euro-classical solo fiddle flourish. “The Way You See Me” displays masterful balancing of traded instrumental backing behind Willie’s insistent singing and a gently and slowly walking bass — alternating the more prominent voicing between fiddle, piano and pedal steel guitar in a way that reflects the song’s protagonist’s attempt to put up a dignified and happy facade to conceal his heartbroken loneliness. The vocal choruses combine both male and female voices, which adds a rich textural/timbral dimension. “Lonely Little Mansion” uses sustained vocal backing to add a kind of protestant church aesthetic of serene, austere, atmospherics, somewhat like what Johnny Cash used on songs like the B-side “Were You There (When They Crucified My Lord).” But then “The Last Letter” uses the vocal chorus’ expanding vibrato to emphasize a slight polyrhythm against the song’s core waltz rhythm. The orchestration is never overly complex or abstract. Yet there is still clearly much more effort put into it than on so many other Nashville sound recordings of the day.

After releasing his debut, Willie lamented that he wasted too many good songs on it. In other words, he felt the album was too good and should have been watered down! Unfortunately, that sort of thinking would prevail all too often over his long career. But it is also kind of a self-important statement, because it implies that his own songwriting was inherently better than that of cover songs he might record. Here’s Willie Nelson features a mix of original songs and covers. The covers are quite good though! There is absolutely nothing wrong with something like “Feed It a Memory” or a chestnut like “Roly Poly.” The stately elegance of a song like “Things I Might Have Been” captures the frustrated aspirations that perfectly fits the “countrypolitan” style. He may have choosen some covers rather than all originals here, but nothing is watered down.

Willie’s singing here is much looser and relaxed than on his recordings from later in the 1960s. He also tempers the “jazzy” affectations of his debut somewhat. Though those tendencies are still here. He still sings with a vibrato-less tone way behind the beat. On the opener, the western swing staple “Roly Poly,” he gets so far behind the beat that he barely finishes the verse he’s on before the band has moved on to another part of the song! In these various ways he finds a balance that suits the “countrypolitan” style better than on any of his other recordings in that style. His singing, honestly, isn’t always particularly great on the second side of the album. But it is never bad. But for the most part Willie singing on record became less welcoming for many years, until he passed through a sort of existential personal crisis in the early 1970s.

“Take My Word” is a weaker offering (but is also the shortest song here), as is “Let Me Talk to You,” with Willie limping along with jazzily dissonant phrasing. And, no, nothing here quite matches the heights of the best songs on the debut …And Then I Wrote. But this album still avoids the more jarring discontinuities between Willie’s singing and the studio band’s performances that appeared on his debut, and it manages to be more consistent on the whole. Frankly, Willie wouldn’t make a record this uniformly rewarding until 1971’s Yesterday’s Wine.

The Pagan Appeal of Melodrama

Melodrama is basically pagan in relying on the concept of endless cycles. Melodrama emphasizes emotion untethered to context so that it can repeat, endlessly.

Lars Schall – The CIA: 70 Years of Organized Crime

Link to an interview of Douglas Valentine by Lars Schall:

“The CIA: 70 Years of Organized Crime”

Bonus links: “Operation Paperclip: Nazi Science Heads West” and The Secret Team

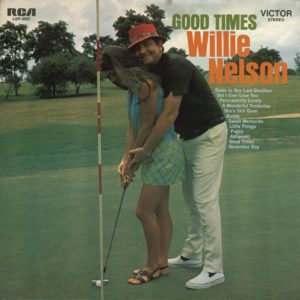

Willie Nelson – Good Times

Willie Nelson – Good Times RCA Victor LSP-4057 (1968)

Even if Good Times isn’t Willie’s best early (pre-fame) album, an argument can be made that it is his most important. All his prior albums on the RCA Victor label in the 1960s looked back to styles that had already been established by other artists. Willie just dropped in his own songs and vocals. Texas in My Soul — amazingly, also released in 1968 — is a Nashville take on western swing and honky tonk that was more popular a decade or two earlier, with really stiff vocals and feigned gravitas. Willie appeared on these early album covers wearing a suit, or dressed as a country bumpkin. He was acceding to industry demands and fitting himself into the mold of what the Nashville music machine deemed salable. Suddenly, though, Willie sounded more relaxed and…modern. This album’s cover features a photo of Nelson in casual attire on a golf course green (he actually really liked golf) with his arms wrapped around some young woman helping her putt, a goofy grin on his face. The photo makes a number of allusions. For one, the presence of the woman and Willie’s grin suggest sexism and patriarchy. Willie’s clothes and association with golf suggest middle class economic security. And his grin and the title lettering stating “Good Times” suggest a shift away from they way he was previously marketed as either a “serious” songwriter or an “authentic” country hick — or both, as kind of an anthropological cultural translator or “cross-over” envoy — instead hinting at a kind of sarcastic and ironic distance. Many of these things seem to stand in conflict with one another. But most importantly there were now multiple plausible meanings and messages. These presented a sort of challenge. How would these conflicts be resolved?

This is an early appearance of the style that would develop into the likes of The Words Don’t Fit the Picture. As another reviewer put it, “Nothing here screams chart topping hit and it must have been nightmare for recording company who wanted to sell this, on the other hand music actually stands the test of time quite nicely and for once it doesn’t sound dated at all but actually timeless. ” His original songs, some co-written with his then-wife Shirley, make extensive use of irony. He had used irony before (“Hello Walls,” “Undo the Right”), but now this was a more melancholy and existential irony. On the title track, “Good Times,” he is describing sarcastically the suburban, middle-class “American Dream” (and the Viet Nam War) alongside innocent childhood activities. This was the sort of stuff much more prevalent in “rock” and rock-influenced pop music of the day. “December Day” even deploys jazzy chords that use dissonance that was (and still is) quite unusual for country music. These descriptions only fit side one of the album though. On side two, Willie is back within the confines of the “Nashville Sound,” with plenty of string orchestration, a little pedal steel guitar, coy backing vocal choruses, and the other usual Nashville trappings. Now, the “typical Nashville” stuff on side two is not bad, and actually is better than many of Willie’s other forays into that territory. But there is a sense of retreat. It is very hard to listen to this now and not lament how much better this album would have been if the whole thing was done in the pared-back acoustic style of side one.

When Willie really hit it big in the mid-1970s, he had a reputation for bringing together rock and country audiences. The fact that he was interested in the music of each of those disparate demographics first made an appearance on Good Times. He hadn’t quite figured out how to balance his appeal to both of those frequently antagonistic listening audiences yet, but this was kind of a trial run. He would continue to tinker and experiment in this direction in to the early 1970s, though as he remained within the Nashville system there was really no way to advance Willie’s line of thinking far enough. It was when he went to New York and teamed up with rock/soul/R&B people that everything finally fell into place on record.

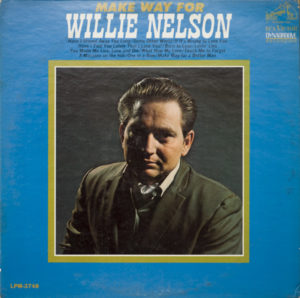

Willie Nelson – Make Way for Willie Nelson

Willie Nelson – Make Way for Willie Nelson RCA Victor LPM-3748 (1967)

Here’s a rather forgotten early Willie Nelson LP that is actually among his better early albums, relatively speaking. Recorded in Nashville, this teamed Willie with producer Felton Jarvis after RCA Records’ main producer Chet Atkins was too busy to handle the recording sessions. This proves to be a boon for the recordings, by sparing them from Atkins’ unsympathetic production style and its usual cloying bourgeois and petite-bourgeois aspirations evident on the same year’s The Party’s Over (And Other Great Willie Nelson Songs), for instance. This is an album recorded much the same way as Country Willie — His Own Songs (1965), another decent early Willie Nelson album. There is only one of Nelson’s own compositions here. These are mostly cover songs. This album can still be described as having the Nashville sound, but it retains a honky tonk influence. Nelson would return to honky tonk on and off again for his entire career. The opening “Make Way for a Better Man” is good, with understated backing orchestration. Other songs like “Have I Stayed Away Too Long?” are decent too, even though the guitar and vocals sometimes sink into a leaden rhythm. There are signs that there was perhaps insufficient rehearsal, and some of these recordings might be first takes. But even if the recordings seem relatively raw at times, that actually suits Willie’s style of singing — actually being crucial to the success of later albums like Yesterday’s Wine and Phases and Stages. There are some odd song choices here, like the 1960s pop staple “What Now My Love [“Et maintenant”]” (even The Temptations released a version of the song in ’67). Willie’s own “One in a Row” is also one of his lesser compositions — recorded here in the same ornate style as “What Now My Love.” On the whole, this holds up well enough all the way through. It isn’t a great album, and it certainly doesn’t do much to distinguish itself from other country albums of the day, but it has a sort of charm in its predictability and familiar approach. As for this album being mostly forgotten, at this writing, the album is not even listed in the Musicbrainz database and there is no track listing in the RateYourMusic database; there is also no review on AllMusic or on RateYourMusic. It was, however, one of his more commercially successful albums at the time, peaking higher on the country music “charts” than any of his other pre-Red Headed Stranger albums.

Willie Nelson – The Party’s Over

Willie Nelson – The Party’s Over (And Other Great Willie Nelson Songs) RCA LSP-3858 (1967)

One of the biggest problem’s with Willie’s singing on his RCA albums in the 1960s was his tendency to over-enunciate. This really put him in a rhythmic straitjacket, and limited his options for vocal phrasing. Aside from the inherent timbre of his voice, one of his greatest strengths as a vocalist was his idiosyncratic, non-conformist rhythmic phrasing — already evident to some degree on his debut album …And Then I Wrote but generally scaled back over the following decade. The sort of ragged, welcoming, down-home glory that characterized his most successful recordings from the mid-1970s on finds no room in a typical Nashville “countrypolitan” production style. But that was kind of the point of middlebrow countrypolitan music, which epitomized the (still racist and sexist) “golden age” of post-WWII American prosperity in which ordinary, uneducated workers saw rising living standards and could see themselves as part of a newly emerging middle class with its own self-styled sophistication — something that might be described as attempting to project an aura of sophistication beyond class boundaries via ideas about “proper” diction and enunciation cribbed from upper classes and merged with lower-class folk/country musical forms. Looked at another way, the temporary willingness of elite classes to permit rising working and middle classes was fostered by inculcating country music listeners with upper-class values as well as the speech patterns and more urban culture that went along with those values (when elites withdrew their permissive and benevolent attitude starting in the 1970s, the countrypolitan style faded almost in lockstep and is now commonly derided as low-class and unsophisticated). When it came to Willie Nelson’s career, the thing was, no matter how many great songs he wrote — and he was writing many — he just wasn’t cut out to follow in the footsteps of someone like Patsy Cline, at least not for long. In the end, Willie was better suited to being a pot-smoking, feel-good layabout with an endearing but weird way of singing that was largely incompatible with the implicit “countrypolitan” agenda of ascending (and reinforcing) a social hierarchy to find a comfortable place in it. Willie was, in a way, proud of his humble roots — post-fame, he often payed tribute to his childhood musical influences, who were always working-class heroes. There was room for all sorts of things in Willie best music, but not on The Party’s Over.

The title track here is a keeper, and a “A Moment Isn’t Very Long” clings to enough of a honky tonk feel to be interesting for the first half. But there isn’t much else here to particularly recommend. This isn’t a bad record by any means, but Willie is choosing to play by a strange set of rules. The lachrymose strings on “To Make a Long Story Short (She’s Gone)” epitomize the bland melodrama that swallows most of this. Excepting Good Times, Willie’s albums got somewhat less interesting in the late 60s, before picking up again in the 70s and then running away with the hearts and minds of listeners by the middle of that decade.