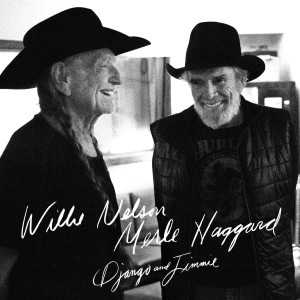

Willie Nelson & Merle Haggard – Django and Jimmie Legacy 8875093782 (2015)

Whenever the olympics are happening, a friend of mine — with clockwork reliability — laments all the “judged” sports. He likes events that are timed, or that assess who crosses the finish line first, and so forth. He despises the way gymnastics and figure skating rely on the whims of judges to rate performances. And he especially hates judged events that multiply a subjective vote against a “degree of difficulty” factor. To him, this results in a lot of botched performances of difficult routines beating out the flawless execution of purportedly less challenging ones. If you are like my friend, you might want to stop reading right now.

Django and Jimmie takes the very commercial sound Willie has been pursuing on his last few Columbia albums, as his touring band has started to die off (literally), and injects a sense of “classic” country tone, rather than being something that tries to go off the map and be “indie” or just a side-project or something, and also does not just adopt boring fads (Band of Brothers, Heroes) without a fight. There are far fewer parallels to Haggard’s recent career. This not the best thing either Nelson or Haggard has done, not by a long shot, but it seems like it deserves marks for having a high “degree of difficulty”. As Slavoj Žižek wrote about Greek acceptance of a brutal financial austerity program in the summer of 2015, “To persist in such a difficult situation and not to leave the field is true courage.” For Willie and Hag, at a late stage in both their careers, to persist in trying to make interesting music in the face of their capitulation to the demands of commercial country music is a stroke of magic, and, if nothing else, courageous. In a way, this is “middlebrow” music that manages, against the odds, to maintain some appeal to the now highbrow (!) “classic country” sensibility.

Although these two veteran performers’ voices may not be what they once were — Haggard’s voice has a much diminished range and is now indeed “haggard” — they benefit from state-of-the-art recording and a crack studio band. Actually, Willie has hardly sounded better on record since the year 2000.

The album’s title refers to two of their musical heroes of yesteryear: Django Reinhardt and Jimmie Rodgers. Yet the sound of these recordings is very contemporary. Jamey Johnson provides a guest vocal, and his own solo recordings mark a decent reference point for the sonic predilections of Django and Jimmie.

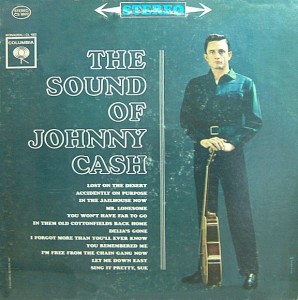

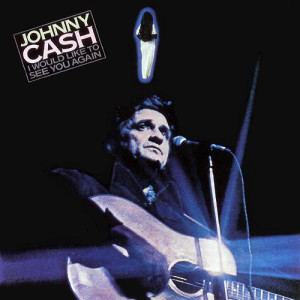

This is perhaps the duo’s strongest collaboration yet. From a strong reading of Bob Dylan‘s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” to a sturdy new recording of Haggard’s “Swinging Doors” to the intriguing new song co-written by Nelson and Buddy Cannon, “Driving the Herd,” to a Johnny Cash tribute, this album covers a lot of territory. The effortlessness in which it looks back and forges ahead with a contemporary sheen is a big part of what makes this music so courageous. Not for a second is there a doubt that the contemporary and the bygone can exist together seamlessly.