A guide by Syd Fablo and Patrick

Introduction

Anthony Braxton

Born: June 4, 1945, Chicago, IL, United States

Currently: Connecticut, United States

In discussing “Braxton’s misleadingly forbidding aesthetic[,]” The Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings (Ninth ed.) comments that “Braxton’s music requires — and deserves — demystification . . . .” Though it might be quite counter to Braxton’s artistic intents to demystify anything, consider this guide a humble attempt to offer an entryway into his catalog of recorded works, which is nothing if not staggeringly large. He has released many dozens of albums as a leader, many on small labels. His recordings were for long periods frequently out-of-print, or available only in a form that was rather expensive. To complicate matters, many of his albums that consistently remained in print were not necessarily his best. Fortunately, digital downloads and streaming services, on the heels of a few physical-format reissue efforts, have made many of his recordings more widely available than ever. For instance, the New Braxton House label has offered many of his most recent recordings plus digital downloads of some long out of print and archival material. However, the availability of old recordings still varies depending on the record label and not everything is available digitally (yet) — and streaming/digital re-releases occasionally alter track sequencing or are abridged. Rather than focus only on recordings currently in print, we focus on what we consider the best, most significant (to Braxton’s career), and most accessible recordings, simply noting as best we can what is in print (or what was in print at the time of writing).

Braxton’s discography can seem, at first glance, rather monolithic; the more things change, the more they stay the same. In other words, his later recordings will almost invariably find precedent in his earlier recordings, even in his very earliest as a leader. Yet there have been developments, mostly in the form of breakthroughs that brought certain elements into greater focus, or that introduced new and different variations on existing approaches. The problem with Braxton’s reputation, too, is that he’s been saddled with descriptions like challenging, daunting, intimidating — you name it. Yet his astute biographer (of sorts) Graham Lock noted on meeting Braxton for the first time, “This is not the super-cold, super-brain of media report; this is a music lover.” As John Litweiler wrote, “His most engaging quality is his nervous vitality . . . [which] results from a romantic attitude that keeps finding new worlds to explore as well as familiar forms to revisit and refreshen.” Braxton’s music may not be for everyone. But there is plenty of excitement, joy, playfulness and more in his music. And, in spite of much puzzlement, bewilderment and outright hostility on the part of some critics, his music avoids bitterness or condescension. Yet it helps to be prepared for music that is simply different from what you’ve heard before, because Braxton is often trying to do something “new”. Anyway, consider this litmus test: if you’ve ever had a real conversation with someone about music, then you’re a potential Braxton fan. If not, and you don’t see that happening, then it may be best to move on to other interests and bypass Braxton entirely. To draw another analogy, if you don’t like books that are about the writing, but simply want a narrative where “stuff happens,” then much of Braxton’s work might not be for you. There is nothing wrong with that, just find what you like, which may be elsewhere — though some of his tribute albums and sideman appearances may still hold interest. As Braxton has said, “In the end, it’s really what you like listening to and being involved with.”

From the beginning of his career, Braxton took particular influence from “cool” saxophonists Warne Marsh and Paul Desmond. But that is not to mention mystical (and even outer space) influences from Sun Ra, a little fire from John Coltrane and Albert Ayler, the unusual use of intervals and an inside/outside stylisitc ambiguity of Eric Dolphy, the compositional insights of Arnold Schönberg and Charles Ives, and the rhythm and wit of Fats Waller. Or for that matter his expressed admiration for artists as diverse as Frankie Lymon, Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band, and Simon & Garfunkel. Yet these points of reference really only barely stractch the surface. He has a faculty on a whole armada of instruments, including obscure reeds from the lowest registers (contrabass clarinet and contrabass saxophone) to the highest (sopranino saxophone). Much of his music deals with linking juxtaposition and combinatorial experiments. Braxton likes to dig into musical history (whether of humankind or simply of his own songbook) and examine bits and pieces, draw different ones together, and offer up the results for what they portend for the future. In many ways, it is the contemplative use of the past and seemingly disparate (even incaongruous) sources in forward-looking ways that Braxton developed from his association with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) that separates his oeuvre from vaguely similar efforts by the likes of, say, James Carter — someone who has evoked inspriations from the past in far more visceral and sentimentally emotive ways than the calm, cerebral, and thoughtful Braxton — or even Sun Ra — someone whose works also turned on a dime from abstraction to the traditional but was far more indebted to the swing era than the younger Braxton, who grew up after that era had passed and had more interest in modern composition originating out of Europe. But Braxton’s compositional efforts are also focused on new methods of organizing musical information, and often less focused on what that information might be. In that respect, the most similar musical traveler out there was probably Karlheinz Stockhausen — Braxton having said, “the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen has helped me on many different levels.” More generally, Braxton has tended to utilize composition as a way to mark the evolution of his music and to avoid getting stuck running out of ideas and repeating himself in concert.

For Braxton, there are three types of musicians, none of which are meant to be a value judgment: restructuralists (who come up with new ways of thinking), stylists (who expand upon the restructuralists’ new ways of thinking), and traditionalists (who operate within a defined space). An example of a restructuralist is Charlie Parker, while a stylist would be someone who expands upon the basic coordinates mapped out by Parker like almost any hard bop player of the 1950s, and a traditionalist would be someone who recreates the past work of Parker while staying within the existing boundaries (who might alternatively be called a neoclassicist). Braxton considers himself a restructuralist, though he makes efforts to record music “in the tradition” regularly — Anthony Braxton´s Charlie Parker Project 1993 being an example.

In various interviews, he has described himself as having a foot in American jazz and another foot in trans-European and trans-Asian musics, but pursuing a composite and trans-idiomatic universalism not confined to any particular tradition. So his music tends to emphasize “and” more than “or”, as in being about this and that, in an inclusionary way, rather than this or that, in an exclusionary way. The way he bristled at being restricted to a particular role as a “jazz musician”, a role put forth as part of politics he calls the “Southern Strategy” or “antebellumist” (that also installed neoclassicists like Wynton Marsalis in the 1980s and purged others; he blames this on liberal identity politics), fits with what Lacanian psychoanalysis calls the discourse of the hysteric. That is, just as feminists question their assigned identity in a social structure premised on patriarchal relations, he questions the social identity and position conjured up and assigned to him. In his specific historical context, Braxton was someone who questioned bureaucratic “expert” rule/apologetics (“university discourse” in psychoanalysis) and the concealed ideological foundations and social ties of the hegemonic sociopolitical structures of late capitalism as manifested through music. This is perhaps one way to contextualize what it means for him to be a “restructuralist”, and why he uses esoteric terminology outside the norm — though certainly not the only way to try to understand such things.

Over his long career, Braxton has written and spoken extensively about his methods, influences, and objectives. So much so that his commentary is potentially overwhelming for newcomers. We have tried to distill a few selected comments here. The other facet of Braxton’s writings is that it tends to share with autodidacts a penchant for esoteric and almost mystical characterizations that requires exploring them deeply enough to reach a kind of “critical mass” where the internal coherence starts to make sense. Newcomers jumping in for the first time trying make sense of it all may want to keep that in mind and reserve judgement or at least hold skepticism and trepidation in check until hitting that critical mass. But that does not have to matter. It is possible (and recommended!) to just listen first and foremost, without feeling obligated to “get” the underlying theory.

A legend is provided below explaining some of the information we have listed for each entry on this list. Each entry includes some release information, with recording date(s), and a “key track” — meant to give you a taste or focal point for each album (especially useful for those who want to buy downloads or stream the music). Selections are organized chronologically by recording date. We have made an attempt to divide Braxton’s career into different periods, but those are somewhat arbitrary on our part. There is good material from all periods. We have also provided a listing for a few additional resources that you might want to investigate if you have an interest, like Graham Lock‘s excellent Forces in Motion book. As a final note, though Braxton’s compositions are identified by a composition number, most have a title that is graphical in nature (the image at the beginning of this guide is our own approximation of one). Braxton has explained, “I say the listener should look at the titles and enjoy them or not enjoy them, but I don’t think you need to understand them in order to listen to the music.” At least for the time being, we have not reproduced Braxton’s graphical titles, but most can be seen here.

The Early Years; AACM; Parisian Expat; Breaking Out: 1967-73

Braxton volunteered for the U.S. Army and played in military bands. He then returned to his native Chicago, and was an early member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM). He studied music academically before and after his time in the army, though never completed a formal degree. He relocated to Paris, but then returned to the United States and lived in New York in Ornette Coleman‘s basement, making money as a chess hustler (and occasional pool hustler). He then took up music again and returned to Paris.

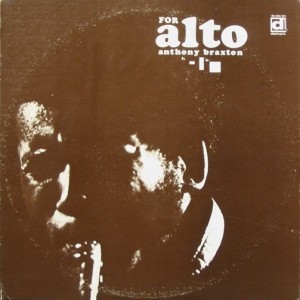

For Alto (1970)

Recorded: 1969, Parkway Community Center, Chicago, IL

Category: Solo

Difficulty Rating: Medium

Key Track(s): “To pianist Cecil Taylor”

Review:

A free jazz masterpiece. But here’s the thing, no one in the music ever set out to make “free jazz” — it’s a common misconception about so-called “free” jazz that the performers of said music simply throw out the rules of jazz and make a lot of noise. What’s free about the music of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor and those who have followed them is that each performer has created their own set of rules to work with, not that they’ve completely thrown out all sense of structure and form. Which of course means that the listener has to work harder — to listen closer than normal and figure things out, then to readjust again to different performers with their own approaches, or listen hard again even when a performer (like Braxton) chooses to change his/her own methods. And this release — Braxton’s third under his own name — is his calling card, cataloging several approaches and strategies he uses in the creation of his music just as Ornette Coleman’s pre-Atlantic albums merely lay the groundwork for his real arrival with The Shape of Jazz to Come. So if Braxton’s earlier records announce him as a member of the AACM, working within the broader ideas essayed by the organization, this one’s pure Anthony Braxton — there’s no more naked way in music than solo performance to open yourself up — and what Braxton has laid down showcases a performer of staggering diversity. It’s not always easy — the tributes to John Cage and Leroy Jenkins in particular can be trying for many ears not attuned to this sort of things — but there are pieces, especially his tribute to Ann and Peter Allen, which are remarkably delicate, introspective, even lovely. There are other solo albums in his extensive catalog that are perhaps easier to digest — a double album of solo alto saxophone is a bit of an undertaking, even for those predisposed to enjoying it, and one might seek out an album of equal quality like Alto Saxophone Improvisations 1979 — but as an introduction to Braxton and his ideas, this is a perfect summary.

Circle – Paris-Concert (1971)

Recorded: February 21, 1971, Maison de l’O.R.T.F., Paris, France

Category: Small Group, Sideman

Difficulty Rating: Medium

Key Track(s): “Nefertitti” (sic)

Review:

Braxton moved to Paris at the end of the 1960s, along with many other jazz players. While some artists found success there, like Art Ensemble of Chicago, Braxton’s group Creative Construction Company did not. So he returned to the United States and lived in New York. He gave up music for a time. But then a reunion show with Creative Construction Company, featuring guests Muhal Richard Abrams, Richard Davis and Steve McCall, brought him out of his temporary retirement. That reunion show brought Braxton into contact with Chick Corea. On the heels of Corea’s 1971 A.R.C. album and trio with Dave Holland and Barry Altschul (and no matter how this is billed feels at this reserve like an instrumental piece of development in Corea’s work, moreso than the development of the other participants) Braxton was invited to join the group formally before it was named after sitting in with the trio. Braxton’s catalog to this point had consisted mostly of works in a very abstract realm, often owing to the tactics of the AACM, and this is one of the earliest pieces of him working in a more identifiably “jazzy” realm, tackling a group of originals (including one of Braxton’s own), a standard (“No Greater Love”), and an interesting recent composition by Wayne Shorter (“Nefertitti” (sic)) that was also part of A.R.C.’s repertoire. And as with the trio, however collaborative the process of the music-making may have been, Corea is the leader here — he makes all the announcements on mike, wrote the liner notes and (though I haven’t measured it strictly) seems to be allotted the most solo space. But Braxton crashes the party, barnstorms the proceedings on “Nefertiti,” deconstructing the work with the fervor he’d bring to his later approaches to standards, while his own “73º Kelvin (Variation – 3)” is for me the most interesting original here, showcasing for the first time on a widely available record the lengthy lines learned from one of his great influences — Lennie Tristano — that later would become one of his signature approaches to composing melodies. For three long pieces plus a series of solos and duets, the group works over their material in a fine example of the sort of rooted jazz with free leanings that Eric Dolphy liked to call “inside and outside at the same time.” As for Braxton? Here’s some of the earliest evidence that when he wanted to he could play it straighter, that his range could extend over not just the abstract sounds of an outsider, but could and did incorporate “the tradition” in the makeup of the music.

Dona Lee (1975)

Recorded: February 18, 1972, Paris, France

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Easy/Medium

Key Track(s): “Dona [sic] Lee”

Review:

Circle broke up, leaving Braxton stranded (a not uncommon circumstance for touring musicians) in Los Angeles. He eventually made his way back to Paris. One notable development of this period was that he started to record standards. Because his own compositions can seem strange to some, standards provide something of a simplification with points of reference to latch on to. A formative experience in the mid-1960s was a John Coltrane concert in which he nearly left when Coltrane played an “out there” solo (!), saying, “I decided this man is crazy, I want nothing to do with it. And the composition came to an end, and then this is what took me out: he played the ballad, ‘It’s So Easy to Remember and So Hard to Forget.’ And he played it straight, and it was beautiful, and it was profound, and it took me out…I found myself with this paradox: how can this guy play so beautifully when he plays this ballad, then he goes back to this other music and it’s all sound again? There must be something happening that I don’t know about!” Just like that epiphany, the track selection and sequencing here provides a potential link from the “straight” material to the more “out there” compositions and solos. This is still building toward the triumphs of the following years. Nonetheless, this is a fine album, with the standards showing an affinity — and faculty — for be-bop, with a little more modern spin on it of course. The new compositions are certainly more challenging, providing an abrupt but still comfortable contrast. Most significantly, this transitional album marks a growing maturity in Braxton’s recordings, as well as in his own performance style. He had softened his attack somewhat as he expanded his palette. Things would only get better from here. But this album is concrete (and early) proof his recordings can be downright approachable at times. There are other worthy recordings from roughly this same time period, even arguably better ones. But Dona Lee nicely highlights Braxton’s growing post-Circle tendency to juxtapose standards with new music as a significant feature of his musical endeavors.

David Holland Quartet – Conference of the Birds (1973)

Recorded: November 30, 1972, Allegro Studio, New York, NY

Category: Small Group, Sideman

Difficulty Rating: Easy

Key Track(s): “Four Winds”

Review:

It is fairly typical for jazz musicians to serve an apprenticeship as a sideman. Anthony Braxton never really did that, at least not as a precursor to a solo career. Although his stint with Circle came closest, he rather infrequently played a supporting role to another bandleader — much like major influence Ornette Coleman. Conference of the Birds is one of his relatively few appearances as a sideman. The group is mostly Circle alumni, with Sam Rivers in place of Chick Corea. Two of the other performers (Holland and Altschul) would go on to have roles in Braxton’s own first great quartet(s) in the coming years. This album isn’t a showcase for Braxton by any means, but it’s still a great one. It is widely regarded as a landmark recording, still connected to past periods of relative commercial popularity for jazz while also mapping out terrains for a more guerrilla existence on the horizon. Skeptics might well start here before moving into Braxton’s own catalog.

The music is very much an extension of that of Circle, but moves further away from elements of classic jazz. It is sophisticated and intellectual with an introverted bohemian flavor. Some songs — “Four Winds,” the title track, and “See Saw” — are based on a head-and-solos format. “Q and A” is more free-form. Still others — “Interception” and “Now Here (Nowhere)” — seem to fall somewhere in between those poles. Holland plays warmly in a friendly and welcoming way, with his signature hints of polite funkiness accentuating clear and crisp melodic statements. Drummer Barry Altschul is a diffuse, understated presence, whose playing is exceptionally flexible and unobtrusive yet remains a key element tying the collective performances together. Braxton emphasizes conventionally pretty qualities in his playing, without giving up his signature style of busy lines colored with extended technique noisiness. Sam Rivers pairs nicely. All together, Holland, Rivers, and Braxton play lyrically in an intimate and complementary way. It is somewhat difficult to articulate in words what exactly makes this album so special. But it does come across as the best of all possibilities, the sort of effort that somehow manages to avoid making trade-offs and instead deliver a lot of different things superbly.

The Arista Years; Small Groups to Large-Scale Works; Side Projects: 1974-80

Braxton was offered (and accepted) a contract with the new major label Arista Records, as its first jazz artist signing. His visibility rose considerably worldwide, and many listeners (or “experiencers” in his terminology) only know his recordings from this period. Musically, he began to expand and refine ideas from his early period. He met his wife Nickie just before leaving Paris to permanently return to the United States.

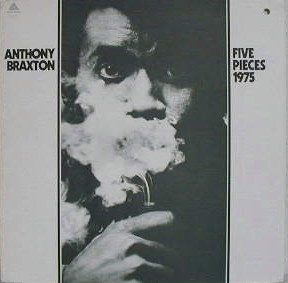

Five Pieces 1975 (1975)

Recorded: July 1-2, 1975, Generation Sound Studios, New York, NY

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Easy

Key Track(s): “Opus 23 G”

Review:

A real stunner of an album and one of Braxton’s all-time best small group records. In it, he and his group (Dave Holland and Barry Altschul from several recent works with Braxton, plus Kenny Wheeler on trumpet to round out the proceedings) navigate a lot of territory with aplomb, working in several modes with equal confidence. The record opens on a duet, Holland and Braxton doing a take on “You Stepped Out of a Dream” and it’s a lovely intro to the record, almost a way of saying to the doubters that what is to follow comes from the same folks who made this piece. On the heels of this is the spare, moody “Comp. 23 H” which deals a lot in coloration more than heavy soloing, but provides an excellent showcase for drummer Altschul nonetheless. Closing the A-side is “Comp. 23 G,” perhaps the finest thing on the album as it perfectly straddles the line between the experimentation and eccentricity of Braxton’s approaches and a more listenable and straightforward approach to same — it’s essentially a head-and-solos piece, though there’s such a long “head” line at the beginning, the soloists move away from the chords, and the rhythm is so fragmented that it doesn’t feel like the standard blowing piece. Still, after the lengthy unison line that starts it, Braxton takes a solo, building in intensity until the climax of his spot and then giving way to Wheeler’s superb work, which in turn allows the rhythm section to shine afterward (though “rhythm section” is a belittling phrase in music such as this where all four players are contributing fully and equally). The B-side opens with the lengthy, dramatic “Comp. 23 E,” a showcase for Braxton in all his glory. It moves through several sequences and he changes horns accordingly — alto sax, flute (twice), and the oddball sound of the contrabass clarinet — to fit the mood of the rest of what’s happening. Again, a slow dramatic build takes place, complete with peaks and valleys, ranging from intense to eerie, over the 17+ minutes of the piece. It’s something of a grand statement, and if there are other catchier pieces on the record there’s nothing this ambitious — in fact there’s little like it in his catalog. The record closes on “Comp. 40 M,” a relatively brief blowout over a bass vamp — another rare thing in the Braxton catalog — that’s sort of like a compact version of “Comp. 23 G,” but provides something like a crooked dance number as it goes toward the fadeout. Alongside Holland’s Conference of the Birds, this is one of the best entry points to Braxton’s music-world for the adventurous listener — accessible enough for most, yet an undiluted version of what he does.

Richard Teitelbaum With Anthony Braxton – Time Zones (1977)

Recorded: June 10, 1976, Creative Music Festival, Mount Tremper, NY, September 16, 1976, Bearsville Sound, Woodstock, NY

Category: Small Group, Collaboration

Difficulty Rating: Medium/Difficult

Key Track(s): Since there are only two side long tracks, either one will suffice. You’ll know within two minutes of either if this is for you.

Review:

Quick — what’s the definition of “jazz”? If your answer is “swung triplets” or any derivative of the word “swing” you can just move on to the next piece. But if that’s your criteria, you’re probably not reading this list anyway. If your answer was “conversation” or some similar idea then you ought to treat yourself to this album, tagged as difficult only because there’s not much like it out there in Braxton’s — or anyone’s — catalog that can give you something similar by which to assess it. Or is there? Throughout two long pieces, Braxton, with his usual array of reeds, duets with a remarkably sensitive Teitelbaum, whose moog synths respond to, query, provoke, and challenge Braxton constantly. There’s a remarkable give and take between the performers, and every time one of them moves into another area of sound — rhythmic, harmonic, melodic, or simply sonic — the other immediately rises to the challenge, meets him there, and moves the dialogue forward yet again. It’s beautiful, bracing, challenging, witty, and even entertaining in the right proportions. Braxton’s music hits all kinds of areas along the spectrum from more composed, fully-formed pieces over to largely improvised works, with this definitely leaning toward the latter, and a great example of such things. So is it so unique? Yes and no — if you have some familiarity with other freely improvised duets — like those of Cecil Taylor in his incredible run of Berlin concerts, or for that matter Taylor and Max Roach, Braxton and Max Roach, or Braxton and Derek Bailey — this may not be so alien. It’s new to hear it done with a moog, yes, but not something completely unknown to you in approach. But aside from Braxton’s duets with Bailey, which I feel are less successful, I can’t off the top of my head think of anything in this style of duetting that predates it. It’s great to hear Braxton, rooted in the African-American jazz tradition but with an ear toward European avant-garde classicism working alongside Teitelbaum, whose background in serial composition had only a few years before this turned his ear toward the forward-thinking jazz of Coltrane, Coleman, and Taylor. Kindred spirits, for sure.

Dortmund (Quartet) 1976 (1991)

Recorded: October 31, 1976, Jazzfestival “Jazz Life,” Dortmund, West Germany

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium-Easy

Key Track(s): “Composition 40B”

Review:

If you like hearing music that takes “classic” mid-century jazz and puts a different, adventurous spin on it, then you have arrived at the right period and album. Dortmund (Quartet) 1976 tends to be a fan favorite. It was recorded just a few days before the West Berlin concerts included on an Arista double album featured elsewhere on this guide, but was not released until the early 1990s. Music from this period of Braxton’s career has made many listeners lifelong admirers. The recordings speak for themselves and feature one of the most lauded small combos Braxton ever led. Trombonist George Lewis is at his very best here. If you want still more like this, the hard-to-find At Moers Festival recorded two years prior might be of interest too.

The Montreux / Berlin Concerts (1977)

Recorded: July 20, 1975, Montreux Jazz Festival, Montreux, Swiss Confederacy; November 4 and 6, 1976, Berlin Jazz Days, West Berlin, West Germany

Category: Small Group, Orchestra

Difficulty Rating: Medium

Key Track(s): “Side Four, Cut One: 29 M 36”

Review:

The Montreux/Berlin Concerts is one of many highlights from Braxton’s tenure on the Arista Records label. It features performances from two different European festivals in 1975 and 1976. The recordings mostly are from two similar quartets with Dave Holland (b), Barry Altschul (d), and either Kenny Wheeler (t) or George Lewis (tb), plus one side-long recording with just Braxton and Lewis performing with The Berlin New Music Group. In many ways this is a culmination of many things Braxton was doing through the 1970s. Much like a comedian who will test out new material in various venues first and then repeat the best and most successful bits and routines for a big show or video/recording, Braxton is not so much trying out new methods here (with the exception of the orchestral track with The Berlin New Music Group) as much as delivering something with techniques he (and his bands) had already perfected. What makes the album so special is that there are some very fine performances here. Arguably, Braxton never led a small combo better than the ones here. And these are stellar performances even from this impressive cast of characters. In Braxton’s world, he deals with “musical informations”. There is certainly a lot of information being exchanged on these sets. Each performer is contributing — solo, spotlight time is shared fairly equally.

When Braxton was the first jazz signing to the new major label Arista, he promised to be some kind of crossover success (see the liner notes to The Complete Arista Recordings of Anthony Braxton and a November 2008 essay in The Wire magazine discussing its release). Leading up to his tenure with Arista, he had recorded works that extended into the territory of modern composition (of the likes of John Cage and the Fluxus movement), but he also worked with more traditional jazz material. He drifted back and forth between the twin poles of traditional jazz and avant-garde composition. But most of the time these were shifts between isolated modes, not truly a “crossover” in the sense of a meeting and melding. On The Montreux/Berlin Concerts he does cross the divide between traditional jazz and modern composition, achieving a synthesis of both within any given piece. There is definitely a sense of connection to traditional jazz throughout. Often a bouncing, free-wheeling, syncopated beat as if from an old Fats Waller tune will be unmistakable. Yet the speed and density of it all will not permit confusion with anything from Waller’s era. The intervals, squeaks and new performance techniques also push this well beyond just the tradition. Again, though, this is crossover music, and so this music is not completely of the “new music” realm of modernist abstraction. It inserts, modifies, expands, deconstructs, and borrows from the tradition at will, but never feels constrained by it. It is the much talked-about but less frequently achieved notion of playing “inside” and “outside” at the same time. This is an album by an artist who has found his voice and is using it to the best of his abilities. It makes for an excellent listen. Some listeners less interested in modern composition gravitate more to the more purely “jazzy” stuff Braxton released elsewhere. Take your pick, but consider giving this a try because it makes an excellent gateway to all sorts of other things in Braxton’s catalog, and beyond.

Quintet (Basel) 1977 (2001)

Recorded: June 2, 1977, Safranzunft, Basel, Swiss Confederacy

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium-easy

Key Track(s): “Composition 69 G”

Review:

With success came new challenges. Members of Braxton’s quartet — Holland and Altschul — were becoming so sought after that they were no longer regularly available and Braxton eventually dissolved the group. In a kind of transitional period, he formed a short-lived quintet featured here, with George Lewis (tb) from the old quartet, plus long-time AACM compatriot Muhal Richard Abrams (p) as well as Mark Helias (b) and Charles “Bobo” Shaw (d). Shaw is more of a “fire music” player who brings a lot of pure energy to the proceedings, often giving the music a relentless, frenetic intensity not always associated with Braxton’s music. Helias deftly acts as something of a bridge from Shaw to the rest of the players who had more history inside Braxton’s working methods. All the performers, Braxton included, are spurred into different and exciting areas. Earlier in the same year Braxton and Abrams had recorded Woody Shaw‘s The Iron Men, and it is possible to say this bears a few vague similarities but at the same time tilts more in the direction of free jazz, with a bit heavier dose of angularly busy soloing. Some of the songs draw noticeably from hard bop traditions, like “Composition 69 G” and “Composition 40 B.” There are also plenty of funny, comedic moments, swinging group statements, and loose, modern solos. For instance, “Composition 69M” is a piece that seems more Braxtonish and AACM-like, and Abrams’s performance is perhaps his finest of the set. “Composition 69 N” has slow, eerie, foggy qualities. In general, everything has a tendency to shift around stylistically, without losing a sense of fluidity. What holds a lot of this together are the compositions, and their juxtaposition. They tend to make the relatively small combo sound bigger than itself, as part of a larger scheme. Somewhat obliquely, this points toward Braxton’s evolving and expanding use of composition to mediate performer improvisations in new ways in the post-free era. A selection of some of the seventeen parts of Composition 69 featured on this set would go on to see extensive use with Braxton’s second great quartet(s) over the subsequent decade-and-a-half, while “Composition 40B” was featured on the prior year’s Dortmund (Quartet) 1976, which is partly why this recording can be called transitional apart from the fleeting assemblage of personnel. But it’s a great one unto itself, regardless of what came before or after.

Creative Orchestra (Köln) 1978 (1995)

Recorded: May 12, 1978, Großer Sendesaal WDR, Köln, West Germany

Category: Orchestra

Difficulty Rating: Easy-medium

Key Track(s): “Comp. 58”

Review:

In effect, this supplants the need for the enjoyable Creative Orchestra Music 1976, by allowing the ensemble more space for improvisation and movement, with hatArt’s usual superb sound (even in this live setting) and extended versions of four of the studio album’s cuts (the two most abstract pieces are excised here, presumably because that sort of spacious music works better in your own home than a concert hall). Essentially, these are pieces that are relatively jazz-like (and in the case of “Comp. 58,” march-like) filtered through the prism of Braxton’s compositional strategies and post-“free” playing techniques by the ensemble, linked together by completely unstructured “free” material (the “Language Improvisations” noted in the first track) making improvised segues between the pieces. Marilyn Crispell, who’d go on to make a great mark with Braxton in a few short years, sounds terrific throughout and Bob Ostertag‘s sculpted synthetic soundscapes also add an element of unsettling weirdness that still feels perfectly right within the context of Braxton’s approach to “jazz.” And when the whole ensemble closes things with the march of “Comp. 58,” which starts out Sousa-like, then slowly goes off the rails, only to draw everything back together in its stellar climax, you know you’re in the hands of a master.

Max Roach Featuring Anthony Braxton – One in Two — Two in One (1980)

Recorded: August 31, 1979, Jazz Festival Willisau ’79, Willisau, Swiss Confederacy

Category: Small Group, Collaboration

Difficulty Rating: Easy-medium

Key Track(s): There are four side long tracks and one will suffice. You’ll know within two minutes of any of them if this is for you.

Review:

Max Roach was one of the pioneers of bebop. Rather than stick to that sub-genre he went in many different directions in subsequent decades with stuff like We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, forays into fusion/soul jazz, and even work with free jazz iconoclasts. In 1978 he recorded Birth and Rebirth with Braxton. The two then appeared at Jazz Festival Willisau the following year, with that performance released as One in Two — Two in One. Just a few months later Roach appeared in concert with Cecil Taylor, resulting in the album Historic Concerts. Even though Roach was two decades older than Braxton, the pair had a great rapport and their mutual admiration is clear. This set is a delight. The two are clearly having a lot of fun and it shows. Braxton plays a variety of reeds and Roach plays an assortment of percussive instruments like gong and bells that go beyond a standard drum kit. The music is surprisingly engaging. A spirit of intergenerational camaraderie allows for a synthesis of different approaches without either player making compromises. While these are free-form improvisations there are plenty of sustained statements (like identifiable melody and syncopated rhythms) and call-and-response interactions that provide a sense of continuity that makes this a good choice for anyone uncertain about this type of performance.

Performance 9/1/79 (1981)

Recorded: September 1, 1979, Jazz Festival Willisau ’79, Willisau, Swiss Confederacy

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium-easy

Key Track(s):

Review:

Recorded the day after the Max Roach duet featured above, at the same festival, this transitional quartet recording highlights how Braxton was pivoting from the music of the first great quartet(s) toward that of the second great quartet(s). Presented on the LP album as nameless side-long tracks, the set list is really a medley of highlights from the Eric Dolphy-esque repertoire of the first great quartet(s) — specifically, parts of Composition Nos. 23, 40, and 69. But this is an entirely different group of musicians, with bassist John Lindberg providing a direct link to the second great quartet lineup. The performances here revel in virtuoso improvisation. More than anything that is the main draw. But what is apparent too is a growing emphasis on collage/montage aesthetics in place of those of the mid-century jazz tradition. The band offers substantial stylistic reworkings of parts of these songs, drawing out interest through jumps and transitions that occur in a fluid manner. Pre-composed melodies do make appearances here and there, but there are lots of collective improvisations and the rhythm section does not merely accompany the wind and brass instruments so much as it improvises right along with one or both of them, simultaneously. In embryonic form, this is already heading in a direction Braxton would explore throughout the 1980s and into the early 1990s. A great one that sort of caps off his mid/late 1970s small jazz combo period with a bang.

For Two Pianos (1982)

Recorded: September 13-15, 1980, Studio Ricordi, Milano, Italy

Category: Composer/Conductor Only

Difficulty Rating: Medium-difficult

Key Track(s): “Comp. 95”

Review:

Braxton was strongly influenced by a number of composers, including Karlheinz Stockhausen, Iannis Xenakis, John Cage, Arnold Schönberg, Ruth Crawford Seeger and Hildegard von Bingen. In his time with Arista, he released multiple modern composition (or “modern classical”) albumsFor Two Pianos was especially written for Frederic Rzewski and Ursula Oppens, each playing piano as well as melodica and zither. It is a work of ritual and ceremonial construction. The musicians perform in costume (floor-length hooded cloaks). The mystical, cryptic messages encoded in the music can, superficially, seem ominous, menacing even, with simple repeating figures (foreshadowing ghost trance music somewhat), but on deeper inspection the interaction of the performers is hopeful. It may be true that not all of the man’s compositions are equally good or successful, but this is one of his better-realized recordings of this type. Braxton has noted his many difficulties in getting his non-jazz compositions performed and recorded, something he attributes in large part to racism (though it is possible to name other factors too).

The Second Great Quartet(s); Professor Braxton: 1981-93

With his major label contract concluded, Braxton entered a period of relative poverty, when he lost his house and couldn’t pay for heat. Then he formed a pair of renowned quartets. Like a number of other jazz luminaries did after the 1960s, he also entered academia, first with a position at Mills College in Oakland, California, and later with a professorship at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut (were he remained until his retirement from academia). During the 1980s he introduced many new ideas to his music, rather than merely continuing to expand upon what he did in the 1970s.

Six Compositions (Quartet) 1984 (1985)

Recorded: September 10-11, 1984, Vanguard Studios, New York, NY

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Easy-medium

Key Track(s): “Composition No. 115”

Review:

Following a transitional period, Braxton formed two quartets in the 1980s and early 1990s that have garnered special reputations among admirers. The first (featured here) included Marilyn Crispell (p), Gerry Hemingway (d), and John Lindberg (b). After a falling out between Braxton and Lindberg, Mark Dresser took over on bass. The trio of recordings with the latter incarnation of the great 80s quartet on a 1985 tour of England tend to receive more attention, but Six Compositions (Quartet) 1984 is a decent place to get your feet wet with Braxton’s 80s output. Vestiges of bop stylings are more pronounced than in many later works of that decade. Although “Composition No. 114 (+ 108A)” proves that Braxton’s methods can be totally ineffective at times, the rest of the album is good — and rather welcoming. The musicians have a great rapport. Pianist Marilyn Crispell deserves special attention here.

Quartet (London) 1985 (1988); Quartet (Birmingham) 1985 (1991); Quartet (Coventry) 1985 (1993)

Recorded: November 13, 1985, Bloomsbury Theatre, London, England; November 17, 1985, Strathallen Hotel, Birmingham, England; November 26, 1985, Warwick University Arts Centre Studio, Coventry, England

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium/Difficult

Key Track(s): “Composition 124 (+30+96) / Composition 88 (+108C+30+96) / Piano Solo From Composition 30 / Composition 23G (+30+96) / Composition 40N” [disc 1 of the Coventry album]

Review:

A highly-regarded batch of albums recorded on a 1985 tour of England with the second great quartet — also called the forces in motion quartet, as a result of this tour being chronicled in Graham Lock‘s book Forces in Motion: The Music and Thoughts of Anthony Braxton, which makes for worthwhile reading. The 1980s were an odd time for Braxton’s recordings, which tended to be on a smaller scale than the more elaborate “prestige” recordings on Arista the prior decade. Yet he developed substantial new musical ideas and compositional methodologies. Braxton had by this point clearly broken away from the sorts of things he was doing with his first great quartets with Altschul, Holland and Wheeler or Lewis in the previous decade. These three albums are commonly regarded as the peak of his 80s output. The Coventry concert was the final show of the tour and the group has said they made an extra effort to perform well for the benefit of the recording.

This music represents Braxton rethinking his compositional approaches and the ways that pre-notated scores could be utilized in performance. He would continue to expand and rethink these approaches in the coming decades too. Each musician is given a “territory” beforehand by Braxton, which serves to facilitate interaction and provide a starting point, but ultimately there is no limit on what each performer can choose to do in his or her territory. Like composer Ruth Crawford Seeger, he was also using material that could be played simultaneously — he called it coordinate music. This stimulates a kind of collage or montage aesthetic. The notated scores provide passages with melodic and harmonic cohesion of the sort that requires pre-planning, though the overall feel remains very loose and open. The performers have wide latitude to improvise and performances still rely heavily on non-notated spontaneous interactions. Somewhat like Ornette Coleman‘s “harmolodics,” this type of music unfolds in large part based on what the individual performers bring forward. Its success writ large often hinges on having a group of performers with a tacit understanding and mutual respect as well as a relatively high degree of confidence and familiarity with suitable performance techniques. For instance, drummer Gerry Hemingway has said that he would sometimes interpret graphical notation not in terms of the most obvious parameters but instead guiding more abstract qualities like intensity. That is the sort of thinking and contribution that made this particular quartet so special. By the time of this tour, the band had a good rapport although this tour took place relatively early in this particular quartet’s existence. On Braxton’s part, his characteristic style of playing sax with busy lines made up of bursts of many notes colored with squawks, buzzes, and creaks, and capped with a pause or legato phrase, was by now well established. It is featured on these recordings in a particularly freewheeling form.

Decards after these albums were released, Graham Lock’s cassette tape recordings from the tour, including four additional concerts from Sheffield, Leicester, Bristol, and Southampton plus five soundcheck recordings from various locations, were released digitally as Quartet (England) 1985, with individual concerts also available as stand-alone releases.

Six Monk’s Compositions (1987) (1988)

Recorded: June 30 and July 1, 1987, Barigozzi Studio, Milano, Italy

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Easy

Key Track(s): “Brilliant Corners,” “Played Twice”

Review:

Braxton at his most approachable. He is doing his part to keep Thelonious Monk‘s achievements a part of a living musical tradition. He strikes a pleasant balance between faithfully playing these great songs and twisting things about just a bit in his solos. It helps that these are Monk‘s songs, where the winding melodies and jittery rhythms seem like a perfect fit for Braxton’s biting, intellectually playful style. Monk crops up over and over as an influence upon or at least kindred spirit to so many notable free jazz artists — Cecil Taylor‘s early recordings like Looking Ahead! and At Newport being other examples. It is worth mentioning too that this shares much in common with Steve Lacy‘s Reflections: Steve Lacy Plays Thelonious Monk. This is a rather decent Braxton release, especially relative to a other recordings in an era when the quality of his output did dip on occasion, and remains among his better and more highly regarded purely “straight jazz” outings. Though the studio production sounds of its time. Braxton would release a number of albums devoted to another composer’s songs through his career, including ones for Lennie Tristano and Andrew Hill referenced elsewhere in this guide. During this general period, Braxton’s group recordings (setting aside solo ones) tended to separate out music like this that is “in tradition” from that of his “restructuralist” efforts, so that any given album was likely to be just one or the other and not juxtapose elements of both.

Eight (+3) Tristano Compositions 1989: For Warne Marsh (1990)

Recorded: December 10-11, 1989, Sage & Sound Recording Studio, Hollywood, CA

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Easy

Key Track(s): “Two Not One,” “Sax of a Kind”

Review:

This Lennie Tristano tribute is a great, fun outing. The group swings and really invigorates all these tunes. What a ride! The album title refers to these being eight Tristano compositions plus three that technically weren’t written by Tristanto. The album’s subtitle is a dedication to Warne Marsh, who played sax in Tristano’s band with a unique sense of chromaticism and phrase construction and who passed away two years prior to these recordings. Marsh’s name might not be as well known these days but he was a primary influence on Braxton’s playing. For more straight jazz done “in the tradition,” this is one of Braxton’s most conventionally successful. In a blindfold test this might be harder to pinpoint as a Braxton effort than, say, his Monk tribute album from a couple years prior, exhibiting a sleek and modernized style, similar to, say, The David Murray Octet‘s Ming. Braxton has multiple other Tristano tribute albums, with this one characterized by both departing from and holding true to the style of Tristano’s original recordings at the same time, with a briskness and brashness that recalls and expands upon Tristano’s legacy in equal measures. A 1997 recording used a frequently skronkier yet sparser approach, while a 2014 set consistently hewed much closer to the original “cool” style evidenced on old Tristano recordings.

2 Compositions (Ensemble) 1989/1991 (1992)

Recorded: October 23, 1989, Frankfurt, West Germany; February 23, 1991, 2nd Noiseburger Festival, Bürgerhaus Wilhelmsburg, Hamburg, Germany

Category: Orchestra, Composer/Conductor Only

Difficulty Rating: Medium

Key Track(s): “Composition No. 147”

Review:

A collection of two ensemble pieces recorded two years apart with the Ensemble Modern and TonArt Ensemble (using the name Creative Music Ensemble). Braxton had been writing for and recording with large “classical” ensembles for quite some time, and a few such recordings appeared on albums going back to the early 1970s. Much like some work by his friend and influence Ornette Coleman, Braxton’s writing on “Composition No. 147” seems to fit roughly in the camp of post-Second Viennese School “new” music but with a countervailing emphasis on numerical symbology — specifically the number 3. Then on “Composition No. 151,” with its mixture of written and improvised sections, there is more blending with elements of the jazz tradition, something that Ornette also notably pursued, and which perhaps also resembles Alfred Schnittke, especially through its polystylistic inclinations. Aside from utilizing solid compositions, these performances are well-executed. Composers like Braxton and Ornette often struggled to realize performances and recordings of their non-jazz compositions, and when they did it was frequently under sub-optimal conditions, such as without adequate rehearsal time. Fortunately, these recordings are free of those problems. The ensembles are all on board with Braxton’s musical ideas, all thoroughly professional, and the performances are recorded well and presented in full. While some fans lean more toward Braxton’s music with more of a jazz combo format, he was a talented composer and an album like this is well worth a shot — simply adjust expectations going in and don’t expect to hear syncopated rhythms, traded solos, or other familiar trappings of jazz combo music.

Willisau (Quartet) 1991 (1992)

Recorded: June 2, 4 and 5, 1991, Mohren, Willisau, Switzerland

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium/Difficult

Key Track(s):

Review:

(Victoriaville) 1992 (1993)

Recorded: October 10, 1992, Festival International de Musique Actuelle, Victoriaville, Quebec, Canada

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium

Key Track(s): “Composition No 159 (131 + 30 + 147)”

Review:

Although there are a number of second great quartet albums featured in this guide, they might (eventually) come across as exhibiting a very similar style. But (Victoriaville) 1992 is perhaps a change of pace. Parts of it echo the sound of The Cecil Taylor Unit. There are some compositions familiar to the group’s repertoire in play but also newer material. The music tends toward studies of sonic architectures built from parameters like texture, timbre, and rhythm more so than sustained melodic statements—although there are definitely some melodies. Sometimes considered one of this band’s more “difficult” recordings, that really is not the best description. Braxton’s own playing is actually somewhat gentle, for instance. A better description would be a relentless and almost obsessional concentration on bold, dense, medium-length statements by individual players, who are often operating from different territories in parallel or at least in overlapping fashion without a common time signature. This recording is also somewhat unique in that it closes with a rendition of John Coltrane‘s “Impressions” even though this quartet’s recordings usually stick exclusively to Braxton compositions. Bassist Mark Dresser deserves special attention here because he really shines, as does drummer Gerry Hemingway.

Quartet (Santa Cruz) 1993 (1997)

Recorded: July 19, 1993, Kuumbwa Jazz Center, Santa Cruz, CA

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium-difficult

Key Track(s): no specific track, as both discs consist of long suites of music.

Review:

A parting shot from the second great quartet. This can be seen as the culmination of what Braxton and this band had been working away at over the prior decade, at least in the sense that this tends to be a particular favorite for aficionados drawn to this period of Braxton’s music. Though a live performance, this is recorded every bit as well as a studio recording. The music generally follows a pattern of organization, albeit one with a lot of flexibility. So in the first suite, after a more collective statement Braxton gets time to solo, then he steps aside and Marilyn Crispell takes the spotlight roughly a dozen minutes in, then she drops away too and Mark Dresser and Gerry Hemingway have a duet with Dresser soloing, followed by Hemingway getting some time for a solo statement (with no one else playing). Then the rest of band re-enters, in reverse order from how the stepped away previously, and then the group moves on to something else, usually in the form of a different composition. Rinse and repeat. Andy Warhol notoriously predicted that someday everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes. While often invoked as a claim to some kind of entitlement to celebrity, in context, it is more a statement about growing emphasis on spectacle and entertainment as well as a comment on expanding equality and social leveling. But it might be possible to apply that quip to this quartet’s music, as odd as that may seem. Braxton’s music, presented here as long, continuous, suite-like pieces that combine multiple different discrete compositions, provides a platform in which all the performers have their chance to shine as co-equals. Opportunities to solo, or to nudge the group in a particular direction, are shared and traded off. This certainly is not a performance by Braxton and his supporting band but rather by a group working together as a team of distinct individuals. Yet the performers each retain their ability to contribute individually, and they are performing for an audience meant to be intrigued, dazzled, and amused — if in an intellectual sort of way. In Franz Kafka‘s short story “Josefine, die Sängerin oder Das Volk der Mäuse [Josephine the Singer, or The Mouse Folk]” he tells of a society of mice in which an entirely ordinary singer, Josephine, is held out as an exception in a way that (re)frames the structure of a society that is otherwise a matter of collective sameness. This is not what this quartet does — though it might make a closer comparison for some of Braxton’s later-career efforts. Rather, they operate a bit closer to Warhol’s quip.

The Later Years; MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship; More New Working Methods and Musical Informations: Ghost Trance Music, Sonic Genome, Falling River Musics, Echo Echo Mirror House, Lorraine Music, etc.: 1994-present

Braxton developed various new musical techniques and forms in his later years. Often these expanded and elaborated upon ideas first germinated in the 1980s. In 1994 he received a MacArthur Fellowship, referred to informally as the “Genius Grant.” For a considerable time during this period his music revolved around his Ghost Trance Music compositions. He performed and recorded extensively with his students and former students. In the 1990s he and his Tri-Centric Foundation operated his own record label Braxton House, which went inactive but was revived along with a new online label New Braxton House in 2011. With the advent of digital releases of recordings the number of his releases that are multiple hours long has proliferated. There has been no slowing down of either the quantity or intensity of his work compared to anything before. The Tri-Centric Foundation also continues efforts to preserve and disseminate his work.

Octet (New York) 1995 (1997)

Recorded: November 24, 1995, Tri-Centric Festival, Knitting Factory, New York, NY

Category: Large Group

Difficulty Rating: Easy-medium

Key Track(s): “Composition No. 188”

Review:

In the mid-1990s, Braxton developed what he called “ghost trance music” (GTM). The name, and the musical theory, drew in part from native american “ghost dance” music from the late 1800s. He was drawn to that ritual music tradition as a way of compiling and preserving culture facing decimation, through practices that acted like a curtain with the present performers on one side and ancestors on the other. His GTM theories were partly a way of surviving academia, with its stifling bureaucracy and petty competitiveness. But it might also be seen as turning against utopian anarchistic and libertarian thinking as a (destructive or ineffectual) socioeconomic phenomenon during the post-1968 “neoliberal” era and more towards a pragmatic, centralized, “scientific” approach, leavened with a kind of mysticism. He basically shifted from compositional styles developed in the 1980s that — like Ornette‘s “harmolodics” or even AACM music — left a lot unstated in terms of what the performers bring to the table. The theories and methods Braxton used with the second great quartet(s) still had many black boxes that worked out in performance only when placed in the hands of a certain set of talented musicians already on the same page. They were thus reliant on a kind of pre-existing social movement to produce a sufficient quantity of those players. With GTM, he was now looking toward something more comprehensively documented, not in a strict written musical notation sense (even assuming graphical or other non-standard notation) but in terms of establishing definite links between notated materials and performance execution (including cues to performers), while still allowing for open-ended improvisation and some black boxes. It is kind of about the degree of determination and federation that composition and adjacent processes provide without hitting a tipping point where the improvisation becomes too limited and constrained to match the threshold possibilities set out in the 1960s. That he stuck with this approach so long is alone enough to show how important it became to his work. The very earliest GTM recordings were released on the Braxton House label, which was set up by Braxton’s Tri-Centric Foundation that was established in 1994 using funds received from a MacArthur Fellowship — known informally as the “genius grant”. Especially with early GTM compositions and recordings, the general impression is of a sizeable group of musicians playing stepped melodies in unison at a characteristically pulsed rhythm, almost like the group is playing mutant up-and-down sine-wave scales in a roughly homophonic manner, punctuated by individual soloing. This produces a “primary” melody that never ends. The performers are all co-equal. There is no division between featured soloists and backing musicians, and Braxton himself takes on no special role as a performer other than as another part of the collective. Those elements are as evident on this selection as on any of the other mid-1990s GTM recordings from the Braxton House label, which are all of similar quality and substance. It is a markedly different sound from much else in the modern jazz tradition; if anything the closest (if still rather distant) analogs would be marching band music and New Orleans “second line” parade music. While the earliest (species one) GTM efforts can exude some stiffness and formalism, with a lot of repetition, Braxton would later expand and refine GTM over a decade-plus period that spanned different “species” or “classes” that introduced more variation. The current selection is not by any means meant to represent the “best” of GTM. It is represented here because as an early (species one) composition it is potentially easier to comprehend and by being performed with a smaller group it is perhaps more approachable. Another decent introduction, is GTM (Outpost) 2003, which is a smaller combo recording of second species syntactical GTM with more space for familiar free jazz solos, or even Quintet (London) 2004: Live at the Royal Festival Hall, which is a third species piece on which the rhythm section outnumbers the wind players, or possibly Four Compositions (GTM) 2000, which are second species compositions that are relatively easy to follow. But if you want class one GTM with strings, try Ensemble (New York) 1995. If you want GTM with slightly more of a classic jazz feel but also skronkier soloing, try the mostly third species Six Compositions (GTM) 2001. If you want a heavy emphasis on drone qualities, using circular breathing techniques and bagpipes, try the second species Composition N. 247. Or if you want third species GTM performed with vocals and electronics, try GTM (Syntax) 2003. And these just scratch the surface. There are many GTM recordings available that vary from each other just as much as they share core elements in common.

Nine Compositions (Hill) 2000 (2001)

Recorded: May 23-24, 2000, The Cadence Building Spirit Room, Redwood, NY

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Easy

Key Track(s): “Pinnacle,” “Refuge”

Review:

Another lively and highly endearing tribute album, this time honoring Andrew Hill. If the music of Braxton’s first great quartet(s) from the Arista years is your thing, then Hill’s work as a composer and bandleader should be right up your alley. Hill’s recordings in general, and this tribute too, straddle the inside/outside divide, with enough of an “inside” connection to appeal to skeptics of “outside” music. Richard Davis, who played and recorded with Hill extensively (including the original recordings of many songs featured here), has said that of all the famous “free jazz” bandleaders he performed or rehearsed with, Andrew Hill was the only one who would show up for a recording session without any preconceived notions. That is, although Hill tended to compose works with a somewhat conventional head-and-solos format, and he retained connections to conventional tonality, famous free jazz figures known for more “out there” music often had greater pre-planned notions about what their music should sound like. Their techniques (and relationships to tonality, rhythm, etc.) may have been more idiosyncratic than Hill’s, but, contrary to reputation and surface appearances, their music could be less open and truly spontaneous than it might appear. This can bear out if you listen to recordings of free improvisers that can sometimes start to sound the same, relying on the same set of techniques over and over again, just metamorphosing. In an interview, Braxton once said, “In 1967, I gave a solo concert at the Abraham Lincoln Center in Chicago. In that time period, I thought I could approach solo music simply through improvisation. After the first five minutes of the concert, I noticed I was repeating myself. After the second five minutes, I found myself thinking, ‘Well, Braxton, I hate to be the one to say this, but this is horrible’ — and there must be some way to avoid the complexities of existential freedom. Because in fact, I was not interested in freedom or non-freedom. What I wanted was a context where I could evolve my work and have some way to measure change.” Elsewhere he elaborated, “for myself, I was not so interested in listening to some context of total improvised music where the understanding is whatever happens is okay. That might have been interesting in the ’60s and early-70s, and I understand that many people are still interested in that. I salute them. For myself, I’m interested in taking that breakthrough that occurred and connecting it with a broader understanding of fundamentals in a broader context, like a further defined interaction dynamics, architectural dynamics, philosophical dynamics and ritual and ceremonial dynamics. The arguments of the free jazz people and the bebop people have become irrelevant to me.” Others have expressed similar concerns about the risk of completely improvised music being overwhelmed by “melodic obsessions, personal cliches, idea or sound associations, and other autonomisms” (Philippe Carles & Jean-Louis Comolli, Free Jazz/Black Power) or the “dead end” problem that a “totally free piece is a totally free piece, end of concert” (Paul Bley, The Wire, Sept. 2007). A bit like Hill, Ornette Coleman, and others, Braxton tended to use composition to mediate musical performance and sidestep the trap of repetition. Anyway, this album manages to stay completely true to the feel of any classic Hill recording while at the same time the performers are able to offer highly personalized soloing that gives this set its own unique character. There are so many outstanding Hill compositions to choose from that it would be hard to go wrong with any. So, naturally, the band works from a great batch of songs (with selections from Hill’s Point of Departure, Andrew!!!, One for One, and Eternal Refuge). The result is one of the warmest and most charming albums in Braxton’s catalog.

(Victoriaville) 2005 (2005)

Recorded: May 22, 2005, 22e Festival International de Musique Actuelle de Victoriaville, Victoriaville, Quebec, Canada

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium-easy

Key Track(s): “Composition No 345”

Review:

Another ghost trance music performance recorded live at the Victoriaville festival, where Braxton has regularly made appearances for decades. Gone are the pulsed rhythms and endless step-wise melodies of the early GTM compositions. This recording provides a little bit of everything. In the first half, it opens with an idiosyncratically composed group statement, but after about three minutes there are scattered improvisations from different performers. A few harken back to what Braxton was up to in the 1980s and 90s. Yet many of the improvisations feature textural shadings more than melodic statements and there are many muted, quiet passages of considerable length that are nonetheless full of microscopic detail, often with just one or two instruments heard, punctuated with interjections by the entire group or sub-groupings of one or two performers. Eventually things build to a raucous level into the latter half — not entirely unlike some post-rock “epic instrumental” music. And as the piece progresses, there are more relentless collective improvisations. There are also computer-generated electronic sounds, an approach Braxton would explore further with his Diamond Curtain Wall groups. Towards the end of the piece, the music softens and gets quieter again. This album highlights how Braxton’s interests had expanded from a collage/montage approach that integrated different compositions in a fairly serial manner to add more emphasis on the integration of compositions and performances in parallel. Rather than just trading solos and rotating time in the spotlight (though there is a bit of that) the performers tend to exert roughly the same influence throughout most of the piece, presenting the music as that of a single (multifaceted) team rather than that of a collection of individuals, with different instruments providing different timbres and coloring and different co-equal sub-groupings providing harmonic and polymelodic depth. As a sextet, the band is big enough to allow for a variety of different instruments — tuba, violin, bass, saxophones, trumpet, drums, vibraphone, computer electronics, etc. — and the possibility of statements by various sub-groupings, but there are not so many performers as to tend to overwhelm the quieter passages. In just a single 68-minute piece you get to hear just about everything that later-species GTM was about (other than vocals) performed deftly by musicians with a strong connection to Braxton and his methods.

9 Compositions (Iridium) 2006 (2007)

Recorded: March 16-19, 2006, Iridium Jazz Club, New York, NY, (DVD interview from March 17, 2006 at Columbia University, Dodge Hall, New York, NY)

Category: Large Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium

Key Track(s): “Composition No. 350” though any of these pieces should work as well as any other

Review:

Braxton only got better and better in his later years. And unlike many artists who settle into a comfortable pattern of reliving past successes, he relentlessly expanded and rethought his work. This lavish and massive box set may seem imposing, but that scope is really just indicative of how much of a focal point these recordings were for this part of his long career. He’s working with a large ensemble, his 12+1tet, and performing many of his final Ghost Trance Music compositions. Most of the band members are his students or former students. These performers know the music and bring a wealth of personality to it. In many ways, this album is the culmination and fullest realization of certain things Braxton had been working on since his second great quartet was formed in the 1980s. In short, he has created a context to use and reuse his compositions in a way that places minimal limitations on the performers while maximizing the opportunities for constructive group improvisation. It is music like this that places Braxton squarely in the Ornette Coleman school that makes composition a mechanism to achieve what purely “free” playing usually doesn’t, by avoiding a feeling of merely endlessly metamorphosing sameness. He’s also addressing (and consciously avoiding) some of the problems of the “Tyranny of Structurelessness” long ago identified by Jo Freeman, and also described by Karlheinz Stockhausen as the redundancies and non-integration problems left by “spiritual background” anarchism in music. The large ensemble provides a full palate to work with. He uses “diamond clef” notation of his own devising that allows for any transposition by individual performers — here is an example from composition no. 342 (not featured on these recordings) using color-coding and other non-standard graphical notations. Another distinctive feature is the the use of “pulse tracks”, which provide notated passages broken up with brief open periods for free improvisation. The effect (for example, on parts of “Composition No. 354” and most apparent on other albums like Composition N. 247) can be to have a steady rhythm interrupted by slippery “abruption” interludes — not unlike the opening “Hell” segment of like-minded director Jean-Luc Godard‘s film Notre musique [Our Music] with its images frozen and advanced in stuttering, lurching movements. This might be as good as any place to start with Braxton, in some ways, and it certainly is a great one. There is a lot to digest here. Braxton set a limit for each performance using an hourglass, meaning there is roughly nine hours of music here. Suffice it to say, while certain passages of each performance may be more appealing than others to listeners, on the whole, all of the compositions and performances in this collection are of a consistently and comparably high quality. So feel free to jump in anywhere and explore as much or as little as your time and interest permits.

Composition No. 19 (For 100 Tubas) (2011)

Recorded: June 24, 2006, Battery Park City, World Financial Center, New York, NY

Category: Large Group, Composer/Conductor Only

Difficulty Rating: Medium-easy

Key Track(s): “Composition No. 19”

Review:

This later-career live recording of a reconstructed early-career piece for four tuba marching bands playing simultaneously is characteristic of a certain endearing quality of Anthony Braxton’s music. The use of all tubas has a gimmicky, almost whimsical quality to it on the surface (note: this is not his only all-tuba composition). But the surprise is that this is not novelty music at all. It generally maintains a droning, low-frequency rumble with tremendous timbral and textural depth. The piece slowly modulates, with brief surges and interjections, tending to de-emphasize melody and rhythm. Absolutely nothing here sounds anything like familiar marching band music — Braxton has engaged with that elsewhere. If anything, drone doom metal (like Sunn O)))), electronic and electroacoustic works by Iannis Xenakis, Karlheinz Stockhausen‘s overtone-based vocal piece “Stimmung”, or even the minimalism of someone like Morton Feldman would make better comparisons. This recording is slightly lo-fi and it really isn’t a landmark by any means — there also appear to have only been about 65 tubas present. Yet it epitomizes Braxton’s penchant for channeling “serious” and “fun” stuff at the same time, and how such an attitude is a thread that has wound through his many-decade career.

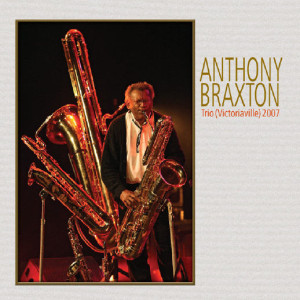

Trio (Victoriaville) 2007 (2007)

Recorded: May 20, 2007, Festival International de Musique Actuelle, Victoriaville, Quebec, Canada

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium

Key Track(s): “Composition N° 323c”

Review:

Recorded by Braxton’s Diamond Curtain Wall Trio, which uses the SuperCollider software program during performance, this is something of an alternate path from Ghost Trance Music. Rather than focusing on composition as the primary guiding and organizational force pushing the music along, the software program moderates the interactions of the performers to a significant degree. Performers are presented with Braxton’s graphical Falling River Music notation (here’s an example photo of a different piece), and the SuperCollider software plays audio patches that Braxton has developed. The resultant music is a little more dynamic — or at least ominous — than a lot of Ghost Trance Music. Braxton had along a lot of his largest saxophones, and they make commanding appearances. Braxton plays so well here you would hardly guess at his advancing years. This trio is also special in that Mary Halvorson (g) and Taylor Ho Bynum (t) are two of the most notable performers to play regularly with Braxton in his later years.

Anthony Braxton / Milford Graves / William Parker – Beyond Quantum (2008)

Recorded: May 11, 2008, Orange Music Sound Studio, West Orange, NJ

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium-easy

Key Track(s): Any track will suffice

Review:

A kind of all-star trio. For free jazz aficionados, Graves (d, v) and Parker (b) are every bit as well-known and respected as Braxton. Here, they play mainly in a format of collective improvisation rather than through traded solos. This might have been recorded at any point in these artists’ careers. In that sense, and almost ironically, this might be call music “in the tradition.” There is a mutual respect evident, and also warm playfulness. This set is a reminder that Braxton could still deliver while operating on common ground outside his own unique musical systems.

Quartet (Moscow) 2008 (2008)

Recorded: June 29, 2008, DOM Cultural Center, Moscow, Russian Federation

Category: Small Group

Difficulty Rating: Medium

Key Track(s): “Composition 367B”

Review:

The format of this Diamond Curtain Wall Quartet recording from Moscow — that’s Braxton grinning in front of Lenin‘s tomb on the album cover — alternates between collective improvisations and individual soloist performances. The focus is on free and open yet orderly improvisation guided by highly abstract graphical notation. There are no pronounced melodies to speak of. The individual solos sometimes involve the other performers dropping completely away, or else providing a kind of sonic texture along with electronic sounds from a computer. The computer-generated sounds are most apparent only at the very beginning of the performance and are much subtler later on. There is no rhythm section in this combo, and even though there is guitar it is utilized for other purposes. When supporting foreground solos, the performers in the background tend to follow an approach more like that of an orchestra behind a featured soloist. Of course, everyone rotates through background and foreground roles. What makes this particular recording stand out is the strength of the performances all around, managing to sound contemporary with a slightly ominous edge.

Trillium J (2016)

Recorded: April 19, 2014, Roulette, New York, NY; April 21 and 22, 2014, Avatar Studios, New York, NY

Category: Orchestra, Composer/Conductor Only

Difficulty Rating: Medium-difficult

Key Track(s): “Act 2”

Review:

Braxton has for a long time written operas. He long planned to write 36 single-act operas, with up to five grouped together. The individual acts have their own