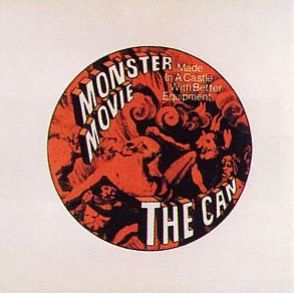

The CAN – Monster Movie Music Factory SRS 001 (1969)

Nobody in rock in the late 1960s really approached recording like The CAN (Jaki Liebezeit said the name’s best meaning was as a backronym for Communism Anarchy Nihilism). No two CAN albums sound alike. On Monster Movie, it is a kind of garage rock drive and primal rhythm that ties much of the album together. This album sounds like CAN recorded it in a modified garage — though the original album jacket noted that it was actually recorded in a castle. It has that rawness you can’t fabricate if you try. There is a little more substance to CAN’s next few albums, maybe, but Monster Movie is on roughly the same level as their next few albums with vocalist Kenji “Damo” Suzuki. This is an important facet of CAN’s sound. They could rock out with somewhat straightforward sounds without sounding straightforward at all. They key was the unabashed interest in rock music as something the equal of modern classical music, which was the background numerous band members came from.

“Father Cannot Yell” ignites the album from the start. It was the first track the group recorded for Monster Movie. Malcolm “Desse” Mooney laces his incredibly musical fuming into the mix — his overdubbed vocals were basically his audition for the band. Mooney — a visual artist really — had an innate talent for shouting/chanting lines with cryptic, ominous, and, yes, obnoxious implications. In live performances he would sometimes pick out an audience member and make him or her uncomfortable by making up lyrics that impugned the character of that person (see “Your Friendly Neighbourhood Whore (1969)” from The Lost Tapes). On “Father Cannot Yell,” there is kind of a proto-feminist undercurrent, with Mooney seeming to take the side of a young woman against a domineering father. This is kind of the template for a lot of Mooney’s singing. He goes into sort of an attack mode, seeking to win listeners over to his position in the process. Call it a kind of “performance art” or, perhaps, purposeful and noble bullying. Mooney just had a great vocal intonation for this sort of music: coarse, deep but still a bit nasal.

“Yoo Doo Right” is an “instant composition” (the group didn’t call it improvisation because what they improvised was form). It’s an unusually long (20 minutes) song for 1960s rock. The group had only minimal equipment. They played and when one of the pre-amps started smoking Holger Czukay decided the song was over. It is the last song on the album, taking up the entire second side of the original LP. But it is also the clear highlight. Mooney is less aggressive than on some other songs, and more pensive, but he still is a catalyst for others to launch into furious solos and interludes.

“Mary, Mary So Contrary” is easily the weakest offering. Mooney chants something from a nursery rhyme, but it lacks the confrontational heroism that is present in most of his best performances. In hindsight, replacing it with something from the vault-clearing collections Unlimited Edition (“The Empress and the Ukraine King”) or The Lost Tapes (“Millionenspiel (1969),” “Your Friendly Neighbourhood Whore (1969)” or “Midnight Sky” (1968)”) would have improved the album considerably.

“Outside My Door” is the most conventional rock song here. At least, it isn’t too far from underground rock coming from New York City and maybe San Francisco around this time. There is a harmonica that weaves a kind of familiar, bluesy melodic thread through the song. It may not match “Yoo Doo Right” or “Father Cannot Yell,” but neither is it a liability to the album.

Monster Movie was the first album the group released. Though they did previously record another, tentatively titled Prepared to Meet Thy PNOOM. The shelved recordings were later released as Delay 1968. It was difficult to find anyone who would release The CAN’s albums. They resorted to releasing Monster Movie in a limited fashion (it was later re-released internationally on United Artists). But the rest, as they say, is history.