Link to an article by Barry Witherden from The Wire Primers (2009):

Tag: Primer

Nina Simone

Nina Simone was an enigma. She is often described as a jazz singer. She wasn’t one of consequence. Stack her next to an actual jazz singer and this becomes pretty clear. She developed a reputation as an artist with moral integrity. Yet that reputation wears thin when looking at how many misguided concessions to pop fads are littered all through her recording career. Much is made of her bitter break from Euro-classical music early in life. Denied entry to a conservatory (The Curtis Institute of Music) as a pianist, she turned to singing in lounges. Little of her piano playing impresses on her own recordings, though it can be effective in accompaniment. But when you hear her voice on a good recording, she definitely had something special. Singing may not have been her desire, but it was her great talent. Sometimes talents choose their medium, rather than the other way around. She was often at her best when adding a rough blues or gospel or jazz inflection to burningly austere chamber pop songs. She was sort of a gothic shadow cast from commercial pop. It was the tone of her voice that embodied a palpable sense of anger that drove so much of it. Close listening doesn’t reveal much clarity in her rhythmic phrasing, her control of vibrato, her pitch range, or even her use of melisma. All that aside, she had the power to deliver songs as if saying, with a firm scowl, “I will sing this song and I will make you remember it.” The single-minded resolve to put her own identity into her music is fiercely determined. This makes the greatest impression on the material that resists that approach. When she worked with jazzy orchestral backing, as was a prevailing style for a time during her long career, the resistance to her identity could be too much. When she played straight blues or even militant soul and R&B, there was nothing really working against her identity to put up any challenge. She reversed her formula and added formal pop technique to rougher electric soul and R&B, and it came across as a reflection of her limitations rather than her positive talent.

What follows is a long yet incomplete set of brief reviews of her albums. This is limited to what I’ve heard, which does not include anything from her time with Colpix Records. Continue reading “Nina Simone”

Collection of Modern Jazz

Welcome to a “virtual” compilation album of jazz from 1960 to 2009, intended to be an introduction to jazz music from that time period for anyone with an interest. It is generally meant to be a follow-up to a compilation like The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, with a focus on a later time period. In moving into more modern periods of jazz history, the listening experience can be more challenging for many because there begin to be marked departures from familiar modes of musical practice. With regard to literary practice, the Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovskii wrote of “laying bare the device” and the technique of “defamiliarization” (or “estrangement”), which are key elements underlying most modernist art movements that, as a general rule of thumb, all rely on a fairly high degree of audience sophistication. The same holds for modern jazz. The music here does get quite challenging at times, and is more along the lines of serious, intensive listening music than casual background or dance music. That is as much a reflection of trends in music history as a reflection of choices among the trove of great recordings that could easily replace the selections here. Every effort has been made to take that into consideration in keeping the overall set as accessible as possible for relatively novice listeners, but without shying away from important recordings that make for challenging listening. All that said, listening to this compilation should probably be prefaced with some understanding of the roots of jazz prior to 1960. The criteria in making selections has been to attempt a reasonable sketch of the musical innovations of modern jazz, with attention also paid to historical trends in the sense of well-known sub-genres. Songs — and some artists — already represented on other compilations like The Smithsonian Collection, have been excluded here to avoid redundancy. It is important to note that this compilation does not track only popular, heavily marketed trends in a rote manner, and so anyone who believes the mainstream account that “jazz just died” at some time in the 1970s should probably look elsewhere for a more sanitized overview that pretends jazz hasn’t kept on surviving at a smaller scale via independent, underground, and publicly-subsidized outlets.

This collection is arranged roughly in chronological order by recording date, though it is not strictly chronologically arranged. For each song selection, the songwriting credits, first release, recording date/location, and personnel are listed to the greatest extent possible, though precise information is not available in every case. Compiler’s notes are given for each selection as a guide for those seeking clues as to suggested musical elements to listen for, as well as to provide reasons for the inclusion of certain tracks. This collection is not comprehensive and exhaustive, of course, and so it does make some omissions of many great and worthy artists and recordings. Moreover, numerous popular movements like “smooth jazz” and “acid jazz” are not represented, as some argue those are not properly called “jazz” at all, at least in the sense that their audiences tend to be outside those historically associated with jazz as such. In order to allow a greater number of different recordings to be represented, while still allowing the collected material to hypothetically fit on a reasonable number of compact discs, many selections are presented in edited form. While those selections deserve to be heard in their complete form, the difficult decision to present edited version seemed necessary given the length of most modern jazz recordings. In earlier eras jazz musicians were limited by recording formats that only offered a few minutes worth of recording time. With technological advances, recordings could be made of indefinite duration. Many musicians have taken advantage of that fact. With the advent of digital music, listeners programming this collection electronically can perhaps ignore the suggested time edits, which are merely a byproduct of the limitations of physical media.

Anyway, the primary objective of this collection is to serve as an educational tool to introduce new listeners to modern jazz. It is hoped this will be a a launching pad for the exploration of the wide and varied interstellar universe of modern jazz. It is hoped that listeners will follow up a careful review of this collection with explorations of other jazz music. The personnel lists, record label listings and compiler’s notes hopefully provide some suggestions for additional listening. But don’t stop there. For more introductory jazz resources, see Jazz Resource Guide. Continue reading “Collection of Modern Jazz”

Zombies, Zombies, Zombies! And Those Who Deal With Them

For decades, “zombies” have preoccupied the makers of films, television shows, comics, and more. What does this genre have to offer? As we’ll see, there is some excellent filmmaking hidden in this genre, though many attempts to extend it are terrifyingly bad.

The earliest zombie films–White Zombie (1932), etc.–were basically typical monster movies, not terribly unlike Frankenstein (1931), or maybe thrillers–like I Walked With a Zombie (1943) that draws on myths of Hatian voodoo. Some of those movies are well regarded, but the “zombie” element was generally confined to a single character with some makeup that converted him into a monstrous “other” that the protagonist has to confront and cope with.

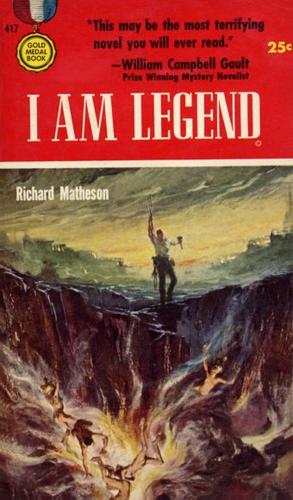

A book, I Am Legend (1954) by Robert Matheson, had a significant impact on the future use of zombies in film. As of this writing, three film adaptations have been made: The Last Man on Earth (1964) starring Vincent Price, The Omega Man (1971) starring Charlton Heston, and I Am Legend (2007) starring Will Smith. While the book and the first movie adaptation relied on vampires rather than zombies, the story structure of having a revolutionary actor (searching for a cure) within an apocalypse of monsters would influence an unknown, independent filmmaker named George A. Romero to run with the idea in a slightly different direction. The latter two film version tended more toward the use of “zombies” than “vampires”, to some degree at least. Omega Man is probably the one to watch among them.

This idea of substituting zombies for vampires even shows up in the spirits industry, with the brewery Clown Shoes changing the name of its American Imperial Stout beer from “Vampire Slayer” to “Undead Party Crasher” after a patent and trademark attorney who co-owned a competing business distributing an imported “Vampire Pale Ale” brought a trademark infringement lawsuit. The new label for the Clown Shoes brew asks if we need the undead and trademark attorneys too. A werewolf-looking trademark attorney is having a stake driven through his heart in a cartoon in the background.

Let’s get back to cinema though. The identifiable genre of zombie films–that of the “zombie apocalypse” movie if you will–came into being with George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968). Romero established himself as the undisputed master to the genre. He made B-movies like director Samuel Fuller or even John Cassavetes, making due with smaller budgets, unadorned camera and editing technique, and minimal technical features like special effects, but packing quite a punch in terms of substantive content. He delivered “soft” science fiction, in which the suspension of disbelief in re-animated corpses is a tool to explore human relations and the human condition. But unlike sci-fi films that may have explored similar human issues, zombies presented a rather simple premise that required only a minimal (if central) suspension of disbelief. There may be zombies, but all else is “normal” in the world. Romero’s films laid out the basic elements of most zombie films to follow: the “undead” (ghouls) coming back to life for unexplained reasons, slow and staggering movement, the need to destroy the head to incapacitate them, herds or swarms of them moving together, and a taste for human flesh. Where the early “monster movie” zombie pictures tended to deal with a main character’s terror of the unknown, or perhaps to suggest that monsters may just want to be like “us”, Romero flipped the relationship and suggested instead that maybe “we” are like zombies. Night of the Living Dead had an existential edge like Sartre’s play No Exit (1944), with its famous assertion that “hell is – other people.” In all of Romero’s later zombie films, though, existentialism was replaced or augmented by questions of consumerism, class consciousness, political (in)equality, and similar social commentary.

Night of the Living Dead established the frequent zombie moving setting of a sudden onset of people turning into zombies, and a group barricading themselves into a house to survive. The threat of zombies infecting others in amass outbreak explains itself easily, lending an air of credibility to an otherwise incredible plot device. Like almost all of Romero’s zombie films, the actors are basically unknown to screen audiences. He also casts the lead as an African-American, at a time when Hollywood did not do so. Most characteristic is that Romero portrays U.S.-Soviet Cold War militarism and social authority as the “real monster”. This placed Romero among the 1960s counterculture, and vaguely attached him to the so-called New Left. Though he remained an independent force, both literally in the sense of existing outside the Hollywood system, but also symbolically int he ideas presented on film.

Night of the Living Dead established the frequent zombie moving setting of a sudden onset of people turning into zombies, and a group barricading themselves into a house to survive. The threat of zombies infecting others in amass outbreak explains itself easily, lending an air of credibility to an otherwise incredible plot device. Like almost all of Romero’s zombie films, the actors are basically unknown to screen audiences. He also casts the lead as an African-American, at a time when Hollywood did not do so. Most characteristic is that Romero portrays U.S.-Soviet Cold War militarism and social authority as the “real monster”. This placed Romero among the 1960s counterculture, and vaguely attached him to the so-called New Left. Though he remained an independent force, both literally in the sense of existing outside the Hollywood system, but also symbolically int he ideas presented on film.

There were many subsequent films Romero made in the same milieu as the original Night of the Living Dead. The first was Dawn of the Dead (1978). To many, and despite rather poor acting, Dawn is the greatest of Romero’s zombie films. Rather than retreating to an isolated home, in this instalment the main characters barricade themselves inside a large shopping mall. The film addresses a legitimate question of realism: what if the government or other people cannot (or simply do not) suppress the rise of the zombies? What happens over a longer time period? Of course, people need food and other supplies. A shopping mall as a mecca of consumerism in the late 1970s is a metanym of consumer culture of the day. Romero’s biggest achievement is to show the zombies taking on “human” qualities, like trying to go to the mall and mindlessly “shop”. Unlike the early zombie films, this did not posit that zombies wanted to be like us but that consumerism has become so ingrained in Western culture that not even death and reanimation as zombies diminishes those impulses. In the 2013 documentary The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek describes the 2011 riots in Great Britain in terms of the inability of the rioters to transcend the predominant ideology of their society, and therefore they act out within that paradigm. Romero’s mall-bound zombies are a very cynical illustration of the same point. What also becomes a trend here is the question of collective action. The onslaught of zombies seems to force the survivors to work together, overcoming whatever objections they have to doing so. In that, a subtle point is made. Working together is more effective that working alone (or against each other). The question is how this can be achieved, and maintained. King Vidor had already made Our Daily Bread (1934), about people founding a collective subsistence farm during the Great Depression, but a zombie apocalypse provides the basis to illustrate the concept more obliquely.

Day of the Dead (1985) seemed, for at time at least, to be Romero’s conclusion of a zombie trilogy. Compared to the first two films, it balances somewhat more refined and modern film technique with more nuanced social commentary. In this version the zombie apocalypse is well underway. A band of survivors holds up in a military installation whilst a resident scientist conducts research on zombies that are (with great effort and risk to humans handling them) corralled into a pen prior to the experiments. The film’s greatest strength lies in the characters. The conflict between the humans and the zombies is merely the setting to explore the tensions between the humans, with class and almost tribal characteristics dividing many of them. Soldiers resent the educated scientist’s pursuits. The civilians and pilots fear the raw aggression and violence of the soldiers. Men despise powerful women. Those in a hierarchy abhor democracy. Another key plot point must be mentioned: Bub. The scientist at the military facility is experimenting to see if the zombies can be controlled and peaceably integrated into human society. Bub (Sherman Howard) is his most promising zombie research subject. While many deride the Bub character (as something like a precursor to Jar Jar Binks of the Star Wars franchise), he represents something completely new for the genre. This is Romero’s lionization of attempts to normalize the most monstrous. It encapsulates the utopian heart of his films. Bub symbolizes a hope and belief that social transformations are possible. He presents an ideology that comes from the zombies. But there is another strikingly radical aspect to Bub as well. He also represents, just oh so slightly, a kind of core goodness of the ordinary man. While most human survivors (especially the soldiers) want the zombies exterminated, Bub is a test case for overcoming the urge to destroy what is different. The interpersonal relations of the characters who are trying in varying degrees to come to terms with these ideas is the axis on which the film turns. Bub may not be a particularly subtle device, but the reactions of the humans around him certainly are. For these reasons, Day of the Dead may be Romero’s very best.

Day of the Dead (1985) seemed, for at time at least, to be Romero’s conclusion of a zombie trilogy. Compared to the first two films, it balances somewhat more refined and modern film technique with more nuanced social commentary. In this version the zombie apocalypse is well underway. A band of survivors holds up in a military installation whilst a resident scientist conducts research on zombies that are (with great effort and risk to humans handling them) corralled into a pen prior to the experiments. The film’s greatest strength lies in the characters. The conflict between the humans and the zombies is merely the setting to explore the tensions between the humans, with class and almost tribal characteristics dividing many of them. Soldiers resent the educated scientist’s pursuits. The civilians and pilots fear the raw aggression and violence of the soldiers. Men despise powerful women. Those in a hierarchy abhor democracy. Another key plot point must be mentioned: Bub. The scientist at the military facility is experimenting to see if the zombies can be controlled and peaceably integrated into human society. Bub (Sherman Howard) is his most promising zombie research subject. While many deride the Bub character (as something like a precursor to Jar Jar Binks of the Star Wars franchise), he represents something completely new for the genre. This is Romero’s lionization of attempts to normalize the most monstrous. It encapsulates the utopian heart of his films. Bub symbolizes a hope and belief that social transformations are possible. He presents an ideology that comes from the zombies. But there is another strikingly radical aspect to Bub as well. He also represents, just oh so slightly, a kind of core goodness of the ordinary man. While most human survivors (especially the soldiers) want the zombies exterminated, Bub is a test case for overcoming the urge to destroy what is different. The interpersonal relations of the characters who are trying in varying degrees to come to terms with these ideas is the axis on which the film turns. Bub may not be a particularly subtle device, but the reactions of the humans around him certainly are. For these reasons, Day of the Dead may be Romero’s very best.

After a two decade hiatus, Romero came back with three more zombie films: Land of the Dead (2005), Diary of the Dead (2007), and Survival of the Dead (2009). All three exhibit more self-awareness of their place in the pantheon of zombie films and use humor more liberally than the earlier Romero efforts. They also update the context by many years, in that like all of Romero’s zombie films they have a contemporary setting.

Diary of the Dead revolves around a group of college students trying to escape and survive from the time that the zombie apocalypse just begins. One of them is an aspiring filmmaker, and he is making a documentary “Diary of the Dead” to document the apocalypse to counter the false information spread by the mass media, who, on the zombie question, are trying to conceal the nature, extent and origins of the zombie outbreak. Diary‘s use of first person camera and the importance it places on alternative media are somewhat forced. The script never convincingly explains how Internet distribution of a guerrilla documentary film would really work, given that it depends on enough of humanity surviving to maintain not just internet communication lines but also electricity. The use of first person camera to draw in viewers and elicit sympathetic reactions can at times feel like a con job. Frankly, The Blair Witch Project (1999) beat Romero to the idea, which is better suited to zombies as mysterious monsters lurking in the shadows, used for fright (like an old Jacques Tourneur film) but nothing more.

Survival of the Dead picks up from a minor plot point in Diary in which a small band of soldiers rob the students. The film revolves around the questions of allegiances and trust, and the interactions not just of individuals but between small groups. The soldiers from Diary seemed like self-interested rogues in that earlier film, but in the latter are redeemed as altruistic and simply in search of survival. They eventually encounter bands of other survivors engaged in the vestiges of a kind of family feud on an island. People who seem trustworthy turn out to be con artists, and others show compassion when it counts. Intended, perhaps, as the most humane of the Romero films, the sometimes low-rent acting, not to mention the less-developed script, doesn’t always allow the surprise twists in the behavior of the characters to seem convincing. Survival seems like the least original of all of Romero’s zombie films because the major themes and interactions between characters are fairly familiar ones. No new perspectives are really made possible by their use in a zombie film. You can find much of this stuff in plenty of old westerns, for instance, and the westerns are better.

This leaves us with Land of the Dead. It is the only of Romero’s zombie films to feature A-list Hollywood actors (Dennis Hopper, John Leguizamo, Simon Baker, Asia Argento, and even Simon Pegg in a cameo). Of the “comeback” Romero films, this is easily the best. The zombie apocalypse has been underway for some extended period of time when the film opens. A group of people use a train-like armored vehicle called “Dead Reckoning” to go out into zombie-infested areas and collect supplies for a gated island city where humans have gathered. The city was a luxury condo/apartment highrise complex, and Kaufman (Dennis Hopper) is a man who has set himself up as the sort of CEO dictator of the facility. He provides amenities such that the rich who live in the highrise maintain their posh standard of living as if there was no zombie apocalypse outside. The rest of the residents of the island are either servants for Kaufman’s city-state empire, or are confined to make due in a ghetto on the streets of the island outside the main building. The main characters have varying degrees of awareness–for some, there are awakenings that play out onscreen–of what Kaufman is up to and the cruel mechanisms he employs to maintain the very divided and unequal society on the island. Many of the main characters take personal risks in order to act with altruism. And there is constant talk of how to topple Kaufman’s empire to foster equality and fairness, balanced against concern for the collateral effects that a revolution presents. In a sort of echo of the Bub character from Day of the Dead, Big Daddy (Eugene Clark) is a zombie who somehow intuitively knows how to use the remnants of human society for his own purposes. He does not need a scientists to teach him how to do these things. He appears initially at a gas station, and clumsily finds a way to use the gas pumps. He teaches other zombies, in a way, how to use other tools from the human world. As the movie progresses, Big Daddy seems to be on a mission to avenge wrongs committed by the humans against zombies. Much like Yertle, the turtle on the bottom of a king turtle’s tower built of his own turtle subjects in the Dr. Seuss story “Yertle the Turtle” (1958), who says, “we too should have rights,” Big Daddy seems to be presenting the question of whether zombies have rights too. One of the main human characters ceases fire around Big Daddy, as if to entertain the notion. The class warfare and inequality of the island city give Land of the Dead much of the same spirit as the earlier Romero movies, even if it also makes overtures to more conventionally polished Hollywood filmmaking technique. It has the hallmarks of the early Romero zombie classics, and almost like the Nineteenth Century French novelist Balzac, it uses the genre to paint a picture of human society through an assortment of specific interactions of individuals. The zombies merely provide a shock to the social structure, and empower (or force) the characters to make their own moral decisions in a relative vacuum of social ritual. Do they recreate what was before or try something else? Rather than expounding pure theory, Romero provides little set pieces for the characters to make discrete choices. What makes Romero so unique is that he uses zombie films to show character interactions that place radical options on the table–the sorts of options that are normally omitted through all sorts of ploys like concision, viability, naivety, and the like. An interesting issue not really addressed by the film is why so many of the characters seem so interested in U.S. currency. Would people really still honor it? That’s probably a question for the proponents of Modern Monetary Theory. Anyway, the only quibble with the film is that Simon Baker seems miscast in the lead role. He’s a bit too affable.

This leaves us with Land of the Dead. It is the only of Romero’s zombie films to feature A-list Hollywood actors (Dennis Hopper, John Leguizamo, Simon Baker, Asia Argento, and even Simon Pegg in a cameo). Of the “comeback” Romero films, this is easily the best. The zombie apocalypse has been underway for some extended period of time when the film opens. A group of people use a train-like armored vehicle called “Dead Reckoning” to go out into zombie-infested areas and collect supplies for a gated island city where humans have gathered. The city was a luxury condo/apartment highrise complex, and Kaufman (Dennis Hopper) is a man who has set himself up as the sort of CEO dictator of the facility. He provides amenities such that the rich who live in the highrise maintain their posh standard of living as if there was no zombie apocalypse outside. The rest of the residents of the island are either servants for Kaufman’s city-state empire, or are confined to make due in a ghetto on the streets of the island outside the main building. The main characters have varying degrees of awareness–for some, there are awakenings that play out onscreen–of what Kaufman is up to and the cruel mechanisms he employs to maintain the very divided and unequal society on the island. Many of the main characters take personal risks in order to act with altruism. And there is constant talk of how to topple Kaufman’s empire to foster equality and fairness, balanced against concern for the collateral effects that a revolution presents. In a sort of echo of the Bub character from Day of the Dead, Big Daddy (Eugene Clark) is a zombie who somehow intuitively knows how to use the remnants of human society for his own purposes. He does not need a scientists to teach him how to do these things. He appears initially at a gas station, and clumsily finds a way to use the gas pumps. He teaches other zombies, in a way, how to use other tools from the human world. As the movie progresses, Big Daddy seems to be on a mission to avenge wrongs committed by the humans against zombies. Much like Yertle, the turtle on the bottom of a king turtle’s tower built of his own turtle subjects in the Dr. Seuss story “Yertle the Turtle” (1958), who says, “we too should have rights,” Big Daddy seems to be presenting the question of whether zombies have rights too. One of the main human characters ceases fire around Big Daddy, as if to entertain the notion. The class warfare and inequality of the island city give Land of the Dead much of the same spirit as the earlier Romero movies, even if it also makes overtures to more conventionally polished Hollywood filmmaking technique. It has the hallmarks of the early Romero zombie classics, and almost like the Nineteenth Century French novelist Balzac, it uses the genre to paint a picture of human society through an assortment of specific interactions of individuals. The zombies merely provide a shock to the social structure, and empower (or force) the characters to make their own moral decisions in a relative vacuum of social ritual. Do they recreate what was before or try something else? Rather than expounding pure theory, Romero provides little set pieces for the characters to make discrete choices. What makes Romero so unique is that he uses zombie films to show character interactions that place radical options on the table–the sorts of options that are normally omitted through all sorts of ploys like concision, viability, naivety, and the like. An interesting issue not really addressed by the film is why so many of the characters seem so interested in U.S. currency. Would people really still honor it? That’s probably a question for the proponents of Modern Monetary Theory. Anyway, the only quibble with the film is that Simon Baker seems miscast in the lead role. He’s a bit too affable.

What about zombie movies outside the Romero universe? There have been many. Some are actually comedies. Return of the Living Dead (1985) (and its many sequels) fit the description as comedies. These films popularized the now-ubiquitous concept of zombies eating people’s brains, not just other parts of them. And because they were made with assistance from John A. Russo (the co-writer of Night of the Living Dead), they follow much of the basic Romero template for zombie behavior. Another comedic portrayal of the standard zombie apocalypse theme was Zombieland (2009). Unlike most zombie films, this was a big-budget Hollywood film. It manages to have some good gags, while trying hard to appeal to a sort of cynical nerd audience, though also dragging in a romantic subplot that could be borrowed from almost any other genre (which should be happy to be rid of it). But Shaun of the Dead (2004) is the reigning champ of zombie comedies. It is a satire of all the zombie apocalypse movies. Much of the cast of the British sitcom Spaced (1999-2001) appears in one form or another–those actors would go on to make a series of satires of different film genres together. The gags hit the right notes. They capture much of what the original Romero movies were about, with witty dialog and excellent performances. The characters make all the dumb mistakes characters always make in these movies. The send-up is self-aware and well-informed.

What about zombie movies outside the Romero universe? There have been many. Some are actually comedies. Return of the Living Dead (1985) (and its many sequels) fit the description as comedies. These films popularized the now-ubiquitous concept of zombies eating people’s brains, not just other parts of them. And because they were made with assistance from John A. Russo (the co-writer of Night of the Living Dead), they follow much of the basic Romero template for zombie behavior. Another comedic portrayal of the standard zombie apocalypse theme was Zombieland (2009). Unlike most zombie films, this was a big-budget Hollywood film. It manages to have some good gags, while trying hard to appeal to a sort of cynical nerd audience, though also dragging in a romantic subplot that could be borrowed from almost any other genre (which should be happy to be rid of it). But Shaun of the Dead (2004) is the reigning champ of zombie comedies. It is a satire of all the zombie apocalypse movies. Much of the cast of the British sitcom Spaced (1999-2001) appears in one form or another–those actors would go on to make a series of satires of different film genres together. The gags hit the right notes. They capture much of what the original Romero movies were about, with witty dialog and excellent performances. The characters make all the dumb mistakes characters always make in these movies. The send-up is self-aware and well-informed.

The most significant film to break from the Romero mold while still presenting a classic “zombie apocalypse” theme was 28 Days Later (2002). In this format, the cause of the zombie outbreak is known and explained from the very beginning of the film. Scientists are conducting biotech experiments that produce uncontrollable rage in test chimps. Animal rights activists trying to liberate the caged animals inadvertently release the disease into the human population. The infected are not the slow, lumping zombies of the Romero movies. The disease causes violent, uncontrolled imperatives to attack living humans. These zombies move quickly, always at a full run. They are almost rabid. The main character somehow survived the onset of the zombie apocalypse while in a coma in a hospital. He awakens 28 days after the outbreak, hence the title (though inexplicably he awakens in an empty hospital on clean sheets). He meets up with some other survivors who know how to navigate the apocalypse, as best as they can, and who understand–and explain and illustrate–that any contact with fluids from the zombies or any bites mean infection. The rest of the film deals with the group of survivors trying to find a military outpost that will protect them from the zombies, and the valor of individuals in the group protecting the others from both zombies and predatory humans alike. The action is taut–this is as much a pure action film as a thriller. The characters are believable and compelling. There is a clear line drawn between good and evil. Above all, though, this film set out a new set of rules for the zombies in zombie films. A sequel 28 Weeks Later (2007) was dreadful. Following the I Am Legend format there is a search for a cure, together with the now typical device of a quarantined city. Filled with main characters who are (contrary to intent) manifestly unsympathetic, the film basically imploded onto itself and can’t end soon enough.

The most significant film to break from the Romero mold while still presenting a classic “zombie apocalypse” theme was 28 Days Later (2002). In this format, the cause of the zombie outbreak is known and explained from the very beginning of the film. Scientists are conducting biotech experiments that produce uncontrollable rage in test chimps. Animal rights activists trying to liberate the caged animals inadvertently release the disease into the human population. The infected are not the slow, lumping zombies of the Romero movies. The disease causes violent, uncontrolled imperatives to attack living humans. These zombies move quickly, always at a full run. They are almost rabid. The main character somehow survived the onset of the zombie apocalypse while in a coma in a hospital. He awakens 28 days after the outbreak, hence the title (though inexplicably he awakens in an empty hospital on clean sheets). He meets up with some other survivors who know how to navigate the apocalypse, as best as they can, and who understand–and explain and illustrate–that any contact with fluids from the zombies or any bites mean infection. The rest of the film deals with the group of survivors trying to find a military outpost that will protect them from the zombies, and the valor of individuals in the group protecting the others from both zombies and predatory humans alike. The action is taut–this is as much a pure action film as a thriller. The characters are believable and compelling. There is a clear line drawn between good and evil. Above all, though, this film set out a new set of rules for the zombies in zombie films. A sequel 28 Weeks Later (2007) was dreadful. Following the I Am Legend format there is a search for a cure, together with the now typical device of a quarantined city. Filled with main characters who are (contrary to intent) manifestly unsympathetic, the film basically imploded onto itself and can’t end soon enough.

The Walking Dead (2010- ) was a surprise hit zombie apocalypse TV show, based on a graphic novel series of the same name launched in 2004 by Robert Kirkman. It is a signature cable channel show. As broadcast networks focused on cheap-to-produce reality shows, cable networks began to finance lavish dramas with production values approaching Hollywood theatrically-released movies more than standard broadcast TV fare. This won large audiences. The Walking Dead is extremely derivative of what came before it. The premise, as the series begins, is that the main character awakens from a coma to find himself in a zombie apocalypse. Sound familiar from 28 Days Later? The zombies are dubbed “walkers” (like in Romero films) and exhibit much the same lumbering movements as all the Romero films. But rather than have anything good or new to say, the show is mostly a melodrama, that is to say a soap opera. The setups are implausible. Many of the characters are inconsistent–constantly changing their personalities just to facilitate a plot twist. This show is terrible.

Hollywood has tried to catch up (and cash in) on the zombie buzz generated by the success of The Walking Dead, much like they did with a “vampire” fad a few years earlier (yet again, zombies are kind of a second wave after vampires). Among those efforts is World War Z (2013). This is a formulaic Hollywood movie through and through. The main character (Brad Pitt) searches for a cause of the epidemic, and also for a cure. Every part of the plot follows the “Chekhov’s gun” principle; foreshadowing is absolute and rigid. The zombies follow the 28 Days Later pattern of being wild and frenzied. Framing of the action borrows heavily from the disaster movie genre. The audience is expected to sympathize with the exceptionalism of the family at the center of the story, and multiple deus ex machina plot twists are needed to keep the story moving. While lavishly produced, with every technical detail nearly impeccable, the story is stupid, derivative and implausible. At least Hollywood’s last big (non-comedy) zombie movie, the Will Smith version of I Am Legend, required you to suspend disbelief only as to the presence of zombies but not with regard to the actions and emotions of the uninfected human characters. No such luck here. No, here we get a character on UN-coordinated missions who brings a satellite phone for personal communication only, making no attempt to communicate with the UN regarding his progress other than to fly around the world trying to reach their base and maybe fill them in at that point. Too bad he did not put the UN on speed dial before he left!

Wholly aside from the movies, “zombie walks,” “zombie pub crawls,” and other such events have arisen with participants donning zombie costumes and makeup. Some of these are just middle class past times. But some take up the spirit of the Romero movies by being used a protests against consumer culture, or other things. In Minneapolis on July 22, 2006 a group dressed up as zombies and lurched through a public festival, with portable audio equipment playing announcements like “get your brains here” and “brain cleanup in Aisle 5.” The police arrested them, claiming at first that it was for “disorderly conduct” but then later saying that use of the audio equipment constituted the illegal display of simulated weapons of mass destruction (“WMDs”) (yes, the police, and later city attorneys, actually asserted this). The “zombies” later won a lawsuit against the police, the court saying there was no probable cause to arrest them.

There is certainly more to the zombie phenomenon than meets the eye. For one, there are more zombie films than can be mentioned here. I didn’t even mention Bruce Campbell movies! But the pervasiveness of zombies in popular culture makes them worthy of note. Hopefully, this little primer offers a head start.

The Beach Boys, An Annotated Tour

RateYourMusic user nervenet‘s excellent Lou [Reed], in order list got me thinking of how I could put together a similar guided tour through a particular artist’s discography that avoids being either a ranked list or a chronological one. So here is my guide to navigating through The Beach Boys’ catalog, hitting the highs, the lows, and points in between.

|

The Greatest Hits Vol.1: 20 Good Vibrations (1999)

|

|

Pet Sounds (1966)The classic Pet Sounds is the place to start if you want to get to know The Beach Boys. It was then-bandleader Brian Wilson‘s coming of age epic. If you are at least in your mid-to-late teens or early twenties, then chances are you’ll connect with something on this album. It’s a lot more introverted that most of the band’s biggest hits (yeah, I know you know those already). But as we’ll see a little later on, introverted songwriting is a big part of what made Brian Wilson a pop music genius. A bonus with this album is that it features a guest, hired-gun lyricist (Tony Asher), who tremendously bolsters Brian’s sometimes undeveloped lyrical sense. However, if you think this is the best album The Beach Boys ever made, you need to read on, because we’ll get to that later… |

|

The Beach Boys Today! (1965)Okay, so we’ve touched on the vaunted Pet Sounds already, so it’s time to go back and pick up on a few earlier albums that led up to it. Frankly, The Beach Boys started out as a teen group and their early albums are very thin. Often pushed to release albums of mostly uninteresting filler, their earliest hits are best heard apart from the early albums (and you’ve heard the hits before!). The Beach Boys Today! is one of the best–probably THE best–of the pre-Pet Sounds albums. You can actually hear the group starting to hit their stride with the full-fledged orchestrated pop that made them great on songs like “Please Let Me Wonder” and “She Knows Me Too Well” that populate side two. But you also get a shot in the arm of fun pop songs on side one, like “Dance, Dance, Dance” and “Do You Wanna Dance.” But what you shouldn’t overlook is the original album-only version of “Help Me, Ronda” (it’s spelled differently than the more popular later version), which is perhaps the best version the group recorded. This album is helped tremendously by the fact that session musicians like Hal Blaine were being used on the records by this point, so that the boys could focus on the vocals. |

|

Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) (1965)Another nice little album that pre-dates Pet Sounds is this one. Although people criticize it for lacking any kind of cohesive vision, it does certainly have a lot of great songs: “California Girls,” the slightly Beatlesesque “Girl Don’t Tell Me,” the best-known version of “Help Me, Rhonda,” and “Let Him Run Wild.” While there are some throwaway tracks here–the bane of the earliest Beach Boys albums–lots of the “filler” is quite enjoyable, if straightforward, vocal pop. |

|

The SMiLE Sessions (2011)We’ve gotten through a few discs now. The truth is, though, you’re probably still listening to Pet Sounds. Actually, you should be, it’s just that good. Well, you’re probably also starting to wonder “How could they follow this up?” At the time, answering that question seemed to trouble Brian Wilson quite a bit too. The planned follow-up was SMiLE. The project, perhaps the most ambitous pop album ever attempted to date, never really came to fruition. Van Dyke Parks, a brilliant lyricists with surrealist tendencies, was brought in to pen the words for Brian Wilson’s music. With some great songs in hand, recording began. But, for whatever reasons (there were probably many), Brian Wilson broke down before the album could be completed and the project was shelved. Of course, one song–the most expensive to record in history–did emerge as a single: “Good Vibrations.” So this album remained a mystery. Instead, Brian retreated to his house. He built an indoor sandbox in his living room. He drained his swimming pool and set up recording equipment in it. From the safety of his own home, and with a few (very few) snippets and songs from the SMiLE sessions, Brian Wilson had The Beach Boys record their next album to actually see release. Smiley Smile. Fast forward a few decades, well, almost four decades actually. Brian is back, and he has released a newly-recorded solo album called Presents SMiLE, after revisiting fragments of the original recordings. He even tours to support that effort. But then, another seven years later, comes the surprise of The SMiLE Sessions. It’s not new recordings of the old songs. These are the old recordings stitched together. At last! Hallelujah! The holy grail of 60s pop! Well, er, almost. No doubt, this is a classic, even decades late. The orchestration soars, the tunes, magnificent. Yet there’s also something not quite right in some of the digital manipulations used to pull together the unfinished recordings for the original album. It’s minor quibble altogether, but it’s one reason not to start your Beach Boys journey here. You’re gonna have to make this a stop on it though. The sunshine daydreaming, the childish mythology, the druggy schizophrenia, the historical compendium-building, the christian moralizing, the hopeful irreverence–The SMiLE Sessions are all that and more. This must be called something other than simply SMiLE, but a newcomer is probably best served sticking to the presentation of the “original” album and skip the bonus tracks (for now), so as to bask in the wonderful vision and not turn it into something tedious. |

|

Smiley Smile (1967)Smiley Smile. To some it is an unmitigated disaster. But it’s my favorite Beach Boys album. If you hate this album, you are probably going to have a pretty different opinion about most of the rest of the catalog (although there might be a few places we agree a little at least). But anyway, this is about as “out there” an album as The Beach Boys ever made. It’s dark at times, full of surreal imagery, and creative as hell. The recordings are a little coarse at times (remember the recording equipment in the swimming pool?). Still, “Wonderful” anticipates Sonic Youth‘s “Little Trouble Girl” by almost three decades. Good luck finding any cut-up mix of eclectic sounds like “She’s Going Bald” anywhere from the same time period, or anything as good from any later period. And “Little Pad” is a perfect statement of the kind of romanticized, dreamy songwriting that from here on out will separate the Brian Wilson fans from all the others. We also have the poppy “Vegetables”, the peppy “Gettin’ Hungry”, and one of the very best ballads the group ever recorded in “With Me Tonight”. And you know, “Whistle In” has the kind of stream-of-consciousness diary-like quality that wouldn’t surface anywhere significant until Mark E. Smith and The Fall resurrected it almost two decades later. But I digress. Needless to say, I for one find the most wildly innovative ideas in the whole Beach Boys catalog on this album. If you want refinement, you’re better off looking elsewhere (like the Kenny G discography). But like I said, this one remains my favorite for its dense, inscrutable charms. |

|

Wild Honey (1967)So this, the follow-up to Smiley Smile, was probably another surprise for those trying to anticipate what The Beach Boys would do next. Wild Honey was the most stripped down, rocking album the group had made yet. The driving title track would become a concert favorite in the coming years (particularly with Blondie Chaplin to play it, but more on him later). This album brought The Beach Boys back into critical regard somewhat, and it inspired a lot of other artists to adopt a more stipped-down recording style too. But really it’s quite simply one of the nicest, most enjoyable and listenable Beach Boys albums around. No, there are no hits you’ll ever hear on the radio (even Smiley Smile ended up including “Good Vibrations”). But the mellow, soulful sound here is just real nice. Later, under Brain’s brother Carl Wilson’s direction, the band would return to a more soul-influenced sound, but the results then would never come close to the heights of Wild Honey. |

|

Friends (1968)Okay, having some familiarity with the hits behind us, the praised Pet Sounds and some very good earlier albums, as well as the travails of SMiLE and its progeny also behind us, it’s finally time to get to probably the best Beach Boys album. Virtually unknown outside of the realm of Beach Boys fandom these days, Friends is the group doing everything at their peak capacity. The songwriting is phenominal. Songs written with Van Dyke Parks for the SMiLE sessions are still showing up here in force. Dennis Wilson even contributes his songwriting for the first time. And if Pet Sounds is a coming-of-age album, this is the one about fully arriving at adulthood. While I’ve driven home the great songwriting already, the songwriting here is really only part of the story. Brian Wilson produced all the Beach Boys material during this era. His talents in producing recorded music were the best this side of Sly Stone. Brian could absolutely perfectly balance instrumentation, timbres, rhythm…heck…EVERYTHING that goes into a recording, that it just astounds me every time I hear this album. But you don’t have to really get into all that to enjoy this album. This is just one of the best pop albums I can think of. It has zero hits you’ll ever hear on the radio (yet again). But I do think part of why people ignore this album is also due the fact that it’s one that largely revolves around reaching adulthood, and let’s face it, that never really happens for a lot of people, or at least they are done listening to pop music by the time it does happen. In that sense, I can understand how some won’t relate. So this one slipped through the cracks. But as Bob Dylan supposedly once said at a Beach Boys concert, “You know they’re fucking good, man.” True. |

|

Sunflower (1970)A good effort for the 1970s Beach Boys. This album has held up better than most from the era. But clearly, they had lost a step by this point (don’t believe the fan hype surrounding this one). The best tracks are the ones with the most input from Brian, like “This Whole World.” You can feel the schmaltz creeping in here though. |

|

Surf’s Up (1971)Here’s an album on which I disagree with a lot of Beach Boys aficionados. I think this is a pretty marginal album. Of course, it does have some essential tracks, namely the closers “‘Til I Die” and “Surf’s Up.” I guess for that reason it can’t be missed. Really, the title track here is one of the very best Beach Boys cuts from any era. But the other stuff, like “Long Promised Road” and “Feel Flows,” are really only mediocre. Plus, we have the return of worthless filler like “Disney Girls (1957)” and “Student Demonstration Time.” Well, all things considered this still beats a lot of other albums… |

|

Surfin’ Safari (1962)Time to come back to reality. Here’s the first ever Beach Boys album. It’s an almost totally forgettable assemblage of filler, with the title track and their breakout single “Surfin'” thrown in. I put this here on the list so that we remember to appreciate how good things were in the late 1960s and into the early 1970s. |

|

Surfer Girl (1963)This is a huge step up from the group’s debut album. We’ve got more hits here. “In My Room”, “Surfer Girl” and “Little Deuce Coupe” were big advances in songwriting. But still a lot of filler. |

|

Shut Down Volume 2 (1964)This mysteriously titled album (there is no “Vol. 1”) makes a few more advances in songwriting with “Don’t Worry Baby” and “The Warmth of the Sun”, and includes the popular “Fun, Fun, Fun.” I think it’s at least as good as Surfer Girl. But still too much throwaway filler! In fact, much of this is far worse than just throwaway filler. “Denny’s Drums” is rightly the butt of many Beach Boys jokes, and “‘Cassius’ Love vs. ‘Sonny’ Wilson” is just as bad. |

|

20/20 (1969)Okay, back to some stronger material. Well, 20/20 isn’t really a cohesive album-length statement like most of the mid-to-later 1960s albums, but it has more good songs than most of the early albums. With the nostalgic fun times hit “Do It Again,” the unique rocker “Bluebirds Over the Mountain,” the Brian Wilson sleeper “Time to Get Alone,” the song supposedly originally written by Charles Manson and the Manson Family “Never Learn Not to Love,” and some more SMiLE leftovers in “Cabinessence” and “Our Prayer,” this one is all over the map. But even so, and even if this release was kind of an attempt to clear the vaults, there are still a lot of good songs present here. You need to hear this at some point. |

|

The Beach Boys in Concert (1973)I like to think of this as one of the hidden gems in the Beach Boys catalog. Coming as a live album in the early-to-mid 1970s, it doesn’t look promising on paper. Brian had stopped touring with the band long ago, and he really wasn’t doing much at all, if anything, with band at this point. And Mike Love was long an advocate of milking the summer fun hits that were easy to perform live (he got his way soon enough). But here, we actually get a lot of great, more complex songs. Even the rambling “Heroes and Villains” from Smiley Smile appears. And a few of the versions of songs from the early 1970s studio albums (“Marcella”, “Leaving This Town”) sound better live than on the studio originals. The value of newish members Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar is clear. Their contributions, though their songwriting is maligned by some, are far superior to wholesale crap like “The Nearest Faraway Place” offered on 20/20 by departed member Bruce Johnston (good riddance! But he would return). I guess you have to like The Beach Boys by this point, and need to have heard some of their poorer albums, to really appreciate this album. It may not be great, and I wouldn’t quite call it essential–it comes close though. But if you have made it this far and are still intrigued, you’ll really enjoy this one. It’s a nice little reminder of why Bob Dylan made his “famous” comment that I mentioned above. |

|

Beach Boys Concert (1964)Okay, this has a wide reputation as being a pretty bad live album. It’s not wholly terrible, but it’s not good either. It has serviceable versions of a few of their early hits, some generally poor covers, and an unfortunate amount of instrumentals–never one of the group’s strengths. You probably don’t even need to listen to this. But by way of contrast, it does show how welcome The Beach Boys In Concert was as a live entry in the catalog. |

|

Carl and the Passions – “So Tough” (1972)When Brian went pretty much into full retirement, his brother Carl Wilson took over the duties of producing the records. He’s in charge here, as the title suggests. Also, with this album, we first hear the new South African members Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar. This is a pretty disappointing record. It has a few decent cuts, without having anything particularly memorable. The soulful blues rock of “Here She Comes,” written and sung entirely by Chaplin and Fataar, is something totally new for a Beach Boys record. It’s a good cut to fool someone with in a blindfold test. Brian’s “You Need a Mess of Help to Stand Alone” may be the best here. But “Cuddle Up,” with string arrangements from Daryl Dragon of Captain and Tennille “fame” is just awful. I don’t want to hear any of this “but it’s a touching performance by Dennis” crap. That shit blows and y’all should know better. |

|

Holland (1973)The Beach Boys were clearly in trouble by this point. They really weren’t very popular anymore, and their last few albums had been decreasing in quality. Some see Holland, which was recorded in the Netherlands, as a comeback album. I’m not one of those people. It’s okay. I think it’s a little better than Carl and The Passions, but not by much at all. Of course, what we have for the album opener is really the last of the leftovers from Brian‘s collaboration with Van Dyke Parks in “Sail On, Sailor.” It’s one of the few really great songs The Beach Boys recorded in the 1970s. The “California Saga” medley starts out fine with the “Big Sur” segment, but it has some dismal lows by the time it wraps with Al Jardine‘s “California” segment. There are some interesting moments elsewhere, but this really is a disappointing album. |

|

Mount Vernon and Fairway (A Fairy Tale) (1973)

|

|

Good Vibrations: Thirty Years of the Beach Boys (1993)

|

|

Brian WilsonPresents SMiLE (2004)If you enjoyed The SMiLE Sessions, it may be worth finding the Brian Wilson Presents SMiLE solo version too. Now, some of you will complain that Brian’s new backing band The Wondermints are nothing compared the original Beach Boys. And some of you will say that these songs, and the album as a whole, seem a bit more concise and streamlined than what had been reported about the aborted original album suggested. And a lot of you will probably find this rendered completely superfluous by The SMiLE Sessions. Well, feel free to complain. If you’ve made it this far down the list, you’ve earned the right to bitch and moan a little. But apart from what this album could have been or whatever, this is still some great music. It is a little out of place 40 years after it was written, but that shouldn’t matter. I was lucky enough to go to the first ever live performance of the album in the United States (me and a slew of middle-aged men wearing tacky Hawaiian shirts). This recording didn’t entirely live up to the live performance for me, but I still like it. |

|

15 Big Ones (1976)This was billed as a great “comeback” for the band. I find it to be a practically unlistenable piece of garbage, with the exception of “Had to Phone Ya.” This was an unmistakable sign that the band’s best times were over. The title refers to 15 big turds, er, crummy tracks. |

|

Love You (1977)Originally a Brain Wilson solo effort converted into a Beach Boys record. Fans like this one for its weirdness and the fact that Brian was back in form, musically. Still, Brian was working without the aid of a lyricist, and so we get a lot of garbage in that department, like a song about Johnny Carson with the line “when guests are boring he fills up the slack.” In spite of the weak lyrics, the goofiness of this is charming, and fun. Chronologically, this is probably the last Beach Boys album worth bothering with. |

|

M.I.U. Album (1978)After Love You, this one was a disappointment. The group isn’t trying very hard, and seems to be just going through the motions listlessly. They hit some pretty low points toward the end of the album (“Match Point of Our Love,” which actually sounds worse than its title!). Still, there are a few halfway decent songs here and most of the album is serviceable, if fairly nondescript and bland. Highly committed fans might get something small from this album, but it is not of general interest. |

|

L.A. (Light Album) (1979)An album emblematic of The Beach Boys’ descent into soft rock purgatory. Most of this is so bland it drifts by without notice, with the better tracks (“Good Timin’,” “Angel Come Home,” “Baby Blue”) not really good enough compared to their best material to cause that much of a stir and the bad tracks (“Here Comes the Night,” “Shortenin’ Bread”) so forced it’s embarrassing. At this point it became clear that no matter how hard the group might try, they simply weren’t going to be able to be truly relevant anymore. Still, the album is listenable for the most part, and fans of the slower material on the group’s various other 1970s albums might like it. |

|

Keepin’ the Summer Alive (1980)By the 1980s, The Beach Boys hardly seemed relevant anymore. Yet Keepin’ the Summer Alive has a few good tunes, including the title track. This is better than the last couple albums, and better than anything that came later. But it also casts the Boys as grumpy old timers desperately trying to summon up the past rather than looking toward the future. |

|

Stack-o-Tracks (1968)

|

|

Little Deuce Coupe (1963)Another novelty. This album features almost entirely songs about cars. The best songs had previously been released on other albums. Not much of interest new here. A by-product of the ridiculous rush to put out “new” albums at too quick a pace. |

|

The Beach Boys’ Christmas Album (1964)Wrapping up the novelty entries in the catalog (pun intended), we have the christmas album. It is short, at less than thirty minutes, but has the classic “Little Saint Nick” and some other good songs (“Merry Christmas, Baby,” “We Three Kings of Orient Are”). It is a novelty though, and nothing essential. Yet the boilerplate, Sinatra-esque orchestral backing utilized at times here may have pointed the way to more satisfying efforts that expanded on those kinds of ideas like The Beach Boys Today!, Pet Sounds, etc. The Beach Boys came back to christmas music in the 1970s with a single “Child of Winter” and then another whole album that was rejected by their label and not originally released–at least some of that material was later released on Ultimate Christmas. |

|

All Summer Long (1964)I needed to hold something back on the list so that the tail end doesn’t seem like just a bunch of marginal later efforts and oddities. This one is another step up from Surfer Girl and Shut Down, Vol. 2, and was their best album up through that point. But it is still a distinct step down from the very best albums in their catalog with the ever present bother of filler from which the early albums never escape. But this one is pleasant, and can be handled all the way through. It’s appropriately titled. |

|

Surfin’ USA (1963)Their second album has the horrid ripoff of Chuck Berry‘s “Sweet Little Sixteen” in “Surfin’ USA.” Nothing too exciting here. |

|

The Beach Boys (1985)This was something of a reunion album after the death of Dennis Wilson. Unfortunately, the album spawned a hit song, which probably encouraged the group to keep going well beyond their prime. Anyway, this one makes extremely overt attempts to sound current, complete with lots of mid-1980s synths and drum machines. Apart from the two mediocre songs that open the album, this could be classified by the UN as cruel and inhumane treatment of its listeners. This is one of those albums that plays in the waiting room to hell–as the universe sadistically waits for you to realize that you are already there. |

|

Still Cruisin’ (1989)This one has that song “Kokomo,” which I HATE. And die hard fans insist that it is the best song on this album (I haven’t heard it fortunately). Mike Love was fully in control of the band by this point. Clearly, he had successfully killed the dream. Surely, the band could sink no lower…. |

|

Summer in Paradise (1992)I think everyone with functioning ears would have been happy if The Beach Boys just hung it up after Love You or even L.A. (Light Album). But instead, we have a parade of worthless junk tarnishing the catalog from the 1980s onward. An album like this with John motherfuckin’ Stamos singing Dennis Wilson‘s “Forever” is perhaps the lowest of the low for the band (though, admittedly, it’s not that bad, and even better than some of the stuff the band proper was up to at this point). Although, with some of the original members still alive (Mike Love, Al Jardine…looking in your direction) I won’t hold my breath on that. |

|

Dennis WilsonPacific Ocean Blue (1977)The one solo album Dennis Wilson completed before his drowning death. This makes the list to redeem that John Stamos track from Summer in Paradise, because it’s a fine album that is as good or better than anything The Beach Boys did from the 1970s forward. Also be sure to check out Dennis in the great cult film Two-Lane Blacktop (1971). |

|

Beach Boys’ Party! (1965)A quickly tossed off album that few seem to like. It’s actually much better than it seems. Despite a lack of Brian Wilson originals, covers of the likes of The Beatles are choice. There is a lot of energy here, and it’s a fun listen from beginning to end. The vocals and instrumentals aren’t polished, but that’s part of what makes this feel as lively as it does. Beach Boys’ Party! is worth giving a chance for anyone with an interest in the band’s pre-Pet Sounds period. |

|

That’s Why God Made the Radio (2012)A really late career comeback album that’s a roll-back to the group’s Pet Sounds-era music in many ways. The lyrics are corny and there is definitely something artificial in the mix, particularly a feeling that the vocals are electronically processed, but this has touches of what made the group so great in their prime (*ahem*, Brian). If you’ve exhausted everything else in that vein from the early years and still want more this is a better place to look than other post-1980 releases. |

|

Live in London (1970)Some claim this live album is the group’s best. I haven’t heard it to judge for sure. |

|

Endless Summer (1974)

|

|

Classics: Selected by Brian Wilson (2002)

|

Jazz Resource Guide

This is your ticket to learning about jazz. I have collected here resources for people who wish to gain a basic understanding of the “jazz” musical genre as a whole, while avoiding explicit suggestions to particular albums by particular artists or biographic material about particular artists. There are many resources on the genre available, and my goal here is to provide references to only the most reliable sources, rather than to provide a comprehensive listing. Where appropriate, I have placed definitive and exceptional resources in bold font.

Introductory MaterialsBooks:

Other:What Is Jazz? by Leonard Bernstein Note:The best place to start if you are a novice trying to learn about and understand jazz is probably an introductory book. These are worth reading even before you start listing to the music. The reason for this suggestion is that an explanation of some of the broad musical concepts that are common to the genre can help you to listen to jazz music on its own terms, while reducing the chance that predispositions from listening to other musical genres might cloud or inhibit your appreciation of jazz. The best introductory books present a more or less objective background into general concepts without persuading or coercing readers to like or dislike particular artists, songs, or historical movements. |

Introductory Compilation AlbumsGeneral:

Period/Style/Label-Specific:Les trésors du jazz 1898-1943 (pre-jazz influences and early jazz, dixieland and swing) Note:I would recommend listening to a good, well-rounded jazz compilation even before looking to what might be classified as essential jazz albums. These collections can complement an introductory book nicely. There are numerous compilations available that give a representative overview of jazz from its birth through about 1960, but subsequent to that time frame a single representative set does not exist yet (though for a “virtual” compilation of this sort, see Collection of Modern Jazz). Until such a better compilation is made available, I have made some selections from among compilations limited to particular time periods, genres and records labels, though some are certainly imperfect and may still be hard to find. Even with these concessions, some time periods, labels and sub-genres are still not well represented on my list due to the lack of suitable albums for me to mention. |

Jazz History BooksA New History of Jazz by Alyn Shipton Note:Some jazz history books can be a chore to read, but not the better ones. Others can be overly congratulatory or dismissive of certain historical movements or styles, but not the better ones. Some of these “history” books overlap with my category of introductory books, as well as that for musicology and ethnomusicology. But I’ve tried to list here the ones with more widespread appeal, and the ones that complement a basic introduction to jazz music for beginners. |

Album GuidesThe Penguin Guide to Jazz Recordings by Richard Cook and Brian Morton Note:Album guides can be great resources even if you ignore completely any ratings assigned to particular albums. The better ones are those that are relatively comprehensive in coverage, have an easy to navigate layout, are revised often and include information about personnel, recording dates and other album-specific factual data. |

Jazz Writing and Critical AnalysisBlack Music by LeRoi Jones (a/k/a Amiri Baraka) Note:Writings by music critics and the like can be tremendously invigorating and can often cultivate enthusiasm for the jazz genre. However, I would recommend setting this kind of stuff aside until after you have heard some of the music for yourself. React to the music on your own. Then find out how others react to it. |

Jazz Musicology, Ethnomusicology and Musical TheoryThe Jazz Theory Book by Mark Levine Note:Musicology (and/or enthomusicology) and musical theory books can quickly become dense and technical. In other words, many are not for a beginning listener. Actually, a lot of highly academic works that might fall into this category (or the jazz history one) are slight and unenlightening even for experts and jazz insiders. There certainly is no shortage of them. But in the end, this category of resources is recommended for people with a special interest in more of the technical details associated with the performance of jazz music or intensive academic analysis of the music’s history, and perhaps not so much those with only a general interest in listening to jazz music. |

FilmsIntroductions:Unfortunately, I find that many documentary films and TV programs on jazz tend to present rather poor introductions to and overviews of jazz as a whole. Books, compilation albums, and websites make better starting points. Period/Style/Label-Specific: |

Live PerformanceGet out there to a live jazz performance! While your ability to do this may depend upon where you live, attending a concert is a great way to learn about jazz even if you have no clue beforehand what you’re getting yourself into. Don’t shy away. I’ve often heard people comment that appreciating jazz can be a far simpler task when you have the opportunity to see musicians while they perform, as opposed to just hearing them on a recording. |

The Discerning Listener’s Guide to Sly & The Family Stone

A guide to the recorded music of Sly & The Family Stone. Enjoy!

Danny Stewart“A Long Time Away” (1961)

|

|

|

The Beau Brummels“Laugh, Laugh” / “Still in Love With You Baby” (1964)

|

|

Sly & The Family StoneA Whole New Thing (1967)A decent, if uneven, debut. This is what launched one of pop music’s brightest groups. Sly Stone was still working out the details of his musical vision, but tagging along is a fun ride. Even if they don’t quite fully achieve a “whole new thing” here, they at least established that they were gonna try. “Underdog” is a classic. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneDance to the Music (1968)The debut jumped around a bit trying to find precisely what Sly & The Family Stone were going to be about. Dance to the Music locked in to exactly everything that the “whole new thing” title of their debut promised. The songs are all catchy, upbeat, bright, and the lyrics deliver smart wordplay with some social commentary thrown on top. What might be difficult to appreciate in retrospect is that the group was interracial, and included both men and women, at a time when that was not happening elsewhere. They also had a horn section within the group, whereas most soul acts didn’t consider the horn section part of the group proper — like The Memphis Horns who played for just about every Stax Records singer. Most of the songs on Dance to the Music revolve around very similar material. But the group really proves their mettle by making each one sound fresh. Sly gave Miles Davis a copy, and Miles later had to ask for another because the first was worn out from so much use. While that might just seem like a mildly amusing anecdote, it does help explain an underlying strength of the album: the improvisational flair built around irresistible rhythms. |

|

The French Fries“Danse a la musique” / “Small Fries” (1968)

|

|

Sly & The Family StoneLife (1968)This is like a continuation of Dance to the Music. “M’Lady” is quite similar to “Dance to the Music,” for instance. But when you find a good thing, go with it. While not as essential as some of the group’s other albums, if you like their 1960s stuff this is worth seeking out. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneLive at the Fillmore East (2015)An archival live collection recorded shortly after the release of Life. This was initially released as a 2-LP limited edition album, then as an expanded 4-CD set. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneStand! (1969)Generally considered one of the group’s best albums. With “Everyday People” Sly reached the pinnacle of the unbridled optimism of the 1960s, in the process coining the phrase “different strokes for different folks.” The depth and feeling he fit into the space of a short pop song was a spectacular achievement. Stand! established the group as one of the most important pop acts of their time. This is not a bad place to start in their catalog. |

|

Sly & The Family Stone“Hot Fun in the Summertime” / “Fun” (1969)

|

|

Woodstock (1970)“Woodstock” has since become etched on social consciousness as a symbol of 1960s counterculture. Sly & The Family Stone were right there for it. The first album of material from the festival features a medley excerpted from the group’s performance. Additional recordings from Woodstock came out on Woodstock Diary, but it was not until 2009 that the full performance was available on an album. The original Woodstock album might help put the music in some kind of context though. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneThe Woodstock Experience (2009)

|

|

Abaco Dream“Life and Death in G & A” / “Cat Woman” (1969)The group released two throwaway singles (this and “Another Night of Love”) under the pseudonym “Abaco Dream”. “Life and Death in G&A” is a straight funk number, with the largely instrumental “Cat Woman” featuring lingering, psychedelic synthesizer — both oddities unlike anything in the proper Sly & The Family Stone discography. “Cat Woman” is the more intriguing side because it’s quite weird, for a major pop group or otherwise, while the A-side is driving but kind of simple. |

|

Sly & The Family Stone“Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” / “Everybody Is a Star” (1969)

|

|

The First Great Rock Festivals of the Seventies: Isle of Wight / Atlanta Pop Festival (1971)

|

|

Little Sister“Somebody’s Watching You” / “Stanga” (1970)

|

|

Sly & The Family StoneThere’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971)The defining Sly & The Family Stone album is without question There’s a Riot Goin’ on. Whole books have been written about and around this album, so I will only sketch the key details. It represented an abrupt shift from the last album. Now dark, murky sounds dominated. Original band members were departing. Sly was using a drum machine, performing a lot of the music all by himself, and Bobby Womack appears somewhere in the mix. There really isn’t another album like this. Suffice it to say, it’s one of the all-time great rock/pop/soul albums. An absolute essential. |

|

Sly Stone“Rock Dirge” (1971) |

|

Sly & The Family StoneFresh (1973)Not nearly as militant and obtuse as There’s a Riot Goin’ on, Fresh had a crisper funk sound. It’s yet another classic. Few groups have ever produced a series of albums as good as Sly had from the late 1960s through (at least) Fresh. This is one of the essential Sly & The Family Stone discs. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneSmall Talk (1974)Sly took another turn with Small Talk. It had a much quieter, mellower sound than any of the group’s previous albums. The band was different, with a number of new members added and some old ones departed, and even boasted a violinist. This album really is neglected. The mature sound and lyrics dealing with raising a family and other domestic interests offer a new perspective on Sly’s music. Despite having a few weaker moments (like “Mother Beautiful” and “Wishful Thinkin'”), this has held up pretty well. People used to tell author Joseph Heller that his later books weren’t as good as Catch-22, to which he would respond, but what is? To say Small Talk isn’t as good as something like There’s a Riot Goin’ on, or even Fresh, is kind of unfair. No matter what, Sly had to go downhill at least a little as long as he kept releasing material following such magnificent previous achievements. As long as you don’t come to this looking for more of the same, it should be a rewarding listen. Small Talk deserves to be considered among the group’s better albums, even if it’s on a tier slightly below the all-time classics. |

|

Sly StoneHigh on You (1975)High on You was not credited to “& The Family Stone”, which was perhaps a moot point with the original members of the band already disappearing in previous years. This is a respectable funk/soul outing, with a strong title track, though it’s nothing spectacular. The social consciousness that marked so much prior work was now gone and Sly was aiming only for a funky good time, though he generally succeeds in that more modest aim. Sly’s popularity would decline from this point forward. He was not really pushing himself anymore. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneHeard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back (1976)Perhaps due to the critical panning that Small Talk unfairly received, Sly’s next few albums tended to be merely attempts to recreate his “old” aura. Each one was billed as his big comeback. Heard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back is arguably the worst album in the catalog, though even Sly at his worst is at least adequate in the bigger picture. This one drifts into disco era fads at times, sports very bland horn arrangements, and the songwriting is completely forgettable. |

|

Sly & The Family StoneBack on the Right Track (1979)Another lackluster “comeback” album. It is an improvement over Heard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back as far as songwriting goes, particularly in the way this one reckons with changing times and Sly’s fading popularity. Worth it for “Remember Who You Are”, a real gem from Sly’s late period. But this is not the place to start. |

|

SlyTen Years Too Soon (1979)Well, for better or worse, this is one of the earliest remix albums. It’s a bunch of old Sly & The Family Stone hits recast for disco-era dancefloors. Profoundly unessential. |

|