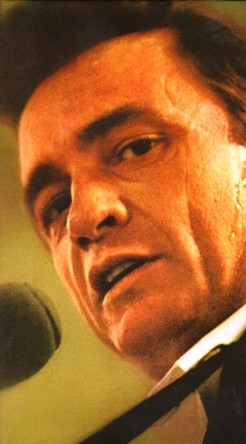

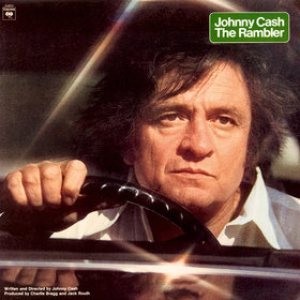

Johnny Cash – The Gospel Road Columbia KG 32253 (1973)

And He spoke, and the multitude assembled contemplated, “Why dost thou release such a substandard recording?” In an era in which double LPs seemed de rigueur, Johnny Cash managed to one-up the proposition by making a film about Jesus and releasing this double LP soundtrack to it. It has all the hallmarks of a big-budget vanity record. It plays like Cash’s thank you note to Jesus for helping him deal with his drug addictions. It has about the same entertainment value and artistic merit as a nondescript thank you note to someone else found out on the street. Only (a) bonzo Cash completists (like me) and (b) religious zealots are really ever going to listen to this, and for those poor saps it will probably be a one-time thing because this has zero replay value — if you make it all the way through the first time that is. Facts aside, it feels like this record is one long speech by Cash. The music is almost something fit in around the narrations, rather than the other way around. If you want just the music, you are denied even that because the narrations are not just interludes between songs but are woven through the songs themselves.

Inasmuch as this album and the movie that spawned it were among Cash’s proudest achievements of his career, it’s worth giving this a more thorough reading. The film, The Gospel Road, wasn’t exactly typical Hollywood fare. It was filmed in Israel, on location where Jesus supposedly lived and preached. Cash was in it, as himself, Robert Elfstrom was Jesus, and June Carter Cash played Mary Magdalene. Something of an independent production, made with a lot of people who aren’t professional actors or filmmakers, this didn’t exactly get major distribution. But Cash worked with Billy Graham to show it to churches and religious audiences.

There is an odd tone to the album. Cash fluctuates. At times he seems to see Jesus as a historical figure and archetype of a “good person” who lived life “right” and to have done so had to be essentially an outsider and revolutionary within his society. It’s a kind of knowing view that although these are religious beliefs there is something more rational behind the stories that make them significant. But then, at other times he seems to take something excessively literal, and there is a deadpan acceptance of the “Jesus was magic” sort of miracle making. Could it be that maybe Cash just took seriously the things that most in society look at as accepted belief rituals and symbols that privately everyone acknowledges are just myths that are regularly told and politely tolerated and not questioned openly? In those moments — there are plenty here — Cash seems naive. It’s a sort of regression. His earliest recordings in the 1950s came from a stylistic place in which rural life was widely recounted and even celebrated with a wise and thoughtful touch. Here he seems like the oblivious fool who doesn’t seem to get that he is proclaiming something quite unsophisticated. “Jesus” just becomes a symbol of something beyond, a life unattainable. At times Jesus is presented as something of a role model — do away with hypocrites, be good to others especially the needy and downtrodden, contribute to your community. But this routinely crosses over into the realm of setting up unattainable, fantasy images, sort of a carrot on a stick. If these moments ended with a wink, an acknowledgement that this is just allegory and not meant to be taken literally, the whole effort might be more palatable. But those moments never come. Cash doesn’t really reveal the wizard behind the curtain as some ordinary joe.

So, the music? There are some good bits. The most intriguing stuff appears on side four, where orchestrated passages with a prominent horn meant to sound “eerie” and unsettling start to approach the sound of modern jazz, and in that are interesting for unintended reasons. Some of the guitar and piano is good in places too. They aren’t featured that much, so that’s a disappointment. Early on there are some overbearing strings placed over the music that get quite tiresome. June carter does a solo song, and Kris Kristofferson and others appears too, with good results. The biggest disappointment, though, is Johnny Cash. His singing is often quite noticeably poor. He sounds downright unrehearsed. He voice is frequently off-key and hoarse almost. The best moments just kind of pass by quickly and the most tedious ones drone on for minutes. Some of these songs might have been interesting standing alone, but with the narrations and fragmentary nature of these versions they don’t add up to much. Take “He Turned the Water Into Wine (Part 1),” for instance. Cash had been performing the song live and on his TV show for years. The version he performed February 11, 1970 at the conclusion of “The Johnny Cash Show” or the similar version included on The Gospel Music of Johnny Cash makes a useful comparison. Live, Cash made the song a multifaceted thing of beauty, with mellow parts just with Cash’s voice and acoustic guitar, then building up with backing vocal choruses and a full band, with Cash’s voice reaching a soaring crescendo and finding opportunities for infectious syncopation. At his best, Cash made the song a marvel of coordination and cooperation between all the many performers. The full song is not just about the wedding at Cana (John 2:1-11), but also about the feeding of the multitude of 5,000 with five loaves of bread and two fish (Matthew 14:13-21, Mark 6:31-44, Luke 9:10-17 and John 6:5-15). The intricate performance by Cash’s band lends the possibility of interpreting these parables as an act of convincing a crowd to share and contribute and being good and generous. But the performance on The Gospel Road is just Cash with guitar and a little plunking and cloying piano, delivering a few lines and then turning to a narration emphasizing the “miracle” of supposedly turning water into wine at the Cana wedding (without reference to the feeding of the multitude). This leaves no room for an allegorical interpretation, only that literally there was an act of “magic” transforming matter against the law of physics. The most wonderful aspects of the other performances are totally absent, leaving a hollow, worthless shell.

In the end, Cash approached The Gospel Road as an effort in proselytizing and religious praise, not as a work of purely musical value. This sounds like a rube gushing about intimate personal details that don’t have a place in public. Lots of gospel music provides a framework to let deep passions, emotions and feelings out in ways they might not otherwise. But, dear reader, this is not one of those opportunities! Musical treatments get short shrift and the audience is almost taken for granted, in the worst possible way. We need to look at The Gospel Road as a token indulgence earned after a long career of good efforts, but not as something to really take seriously. Then it can be safely ignored, like a bootleg copy of home recordings that weren’t ever supposed to be released.