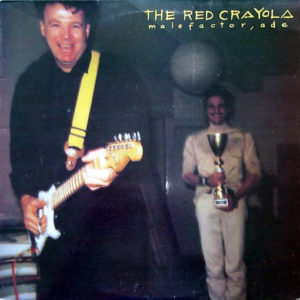

The Red Krayola – Hazel Drag City DC98CD (1996)

The Red Krayola (originally, The Red Crayola) were formed in the late 1960s and quickly became one of the most forward-thinking rock groups of their era. Their debut album, The Parable of Arable Land, is rather unimpressive, and didn’t yet establish the group’s (mostly) unique approach to music. A significant problem with the debut is that it alternates between “songs” by the band and free-form hippie freakouts performed with random hangers on who showed up at the recording studio. This highlights an important error in the goals of the band — and like-minded musicians — early on. While there is a catharsis involved in participating in free-form musical freakouts, and there is something to be said — on paper at least — for conveying to audiences that free-form freakouts are possible and desirable, why bother to record them and release the recordings on an album? This latter question gets glossed over. But it is the crux of the problem. The freakouts have little or no listening value to audiences. Never fear though! Upon some urging from their record label, their second album [after an intended follow-up, Coconut Hotel, was rejected by their label], God Bless The Red Krayola and All Who Wail With It, established the a new and different format that provided an answer to the the lingering question from the first album while still realizing the band’s basic objectives. As Mayo Thompson once put it, “God Bless picks its way through the rubble looking for feeling and meaning, senses of share.”

First off, what were the band’s objectives? This question can be best explained in relation to historical context. The late 1960s were the time of the so-called “New Left”, when left-leaning politics were on the rise and, in the United States and Western Europe, were increasingly centered around students (college students mostly). The band was named The Red Crayola, then changed their name to The Red Krayola (after a largely baseless legal threat from a crayon manufacturer), but kept the word “Red” in the name all along. This was not coincidence or an arbitrary choice of color. The band named themselves in reference to the color historically associated with the political left. The band’s objective remained “musical socialism”.

With the understanding that there was an explicitly leftist political slant to The Red Krayola’s music, their musical techniques can be better understood against the larger backdrop of Twentieth Century art history. Many artists in a variety of media who have sought to pursue leftist ends have adopted techniques that revolve around the use of “montage”. This includes cinematic montage, photomontage, dadism (and offshoots from surrealism to pop art to fluxus, assorted neo-dadaism and even culture jamming), literary endeavors from the Manifesto Antropófago (Cannibalist Manifesto) to “cut ups”, and more.

The term “montage” has been used to describe a number of different musical practices, not all of them similar to The Red Krayola’s, and often in the context of a substantively different “collage” approach. So, here I will use my own term “Diogenic Montage,” in reference to the cynic philosopher Diogenes, whose shamelessly insolent yet witty and outspoken approach to critiquing the powerful has a close kinship with the specific style at hand. (This might equally be called “Kynicist Montage” after Peter Sloterdijk‘s term “kynicism”). Just to illustrate what the philosopher Diogenes stood for, there is a story about him being sold into slavery in Crete, and the slave auctioneer asked what Diogenes was proficient in. He replied, “In ruling men.” He then added, “Sell me to this man [Xeniades]; he needs a master.” The essence of “Diogenic Montage” is to deploy multivalent meanings in a way that is both reverent and irreverent at the same time, with an affinity for the use of “kitsch” and things considered “lowbrow” or in “bad taste” in a framework in which some thing else is either present or suggested, thereby subverting the very basis for highbrow/middlebrow/lowbrow distinctions. There is typically banal ridicule offered, and aspects of French playwright/actor Antonin Artaud‘s “Theater of Cruelty” find their way in as well, although humor appears more often than shocking “cruelty” and Bertolt Brecht‘s “epic theater” might make a closer comparison in The Red Krayola’s instance at least.

One journalist recounted a joke Mayo Thompson frequently told that quite succinctly sums up the kind of humor found in The Red Krayola’s approach to music:

“There’s an anecdote that Red Krayola singer-guitarist Mayo Thompson likes to tell about philosopher of science Sydney Morgenbesser. ‘He’s at some philosophical conference,’ Thompson begins, ‘and some linguist is up there saying, ‘A double negative is always a positive, but there’s no language where a double positive is a negative,’ and Morgenbesser calls out from the back: ‘Yeah, yeah.'”

Diogenic Montage emphasizes symbolic and cultural content, not simply literal and explicit materials, which is why the approach is different from, say, the use of samples in hip-hop music (which could fall in the category, but doesn’t necessarily do so just by the use of samples). Put another way, this is not merely a mechanical technique of juxtaposing and pasting together different elements in any manner, but rather is about pasting together certain elements in certain ways in order to ridicule the supposed “truth” of the referenced/appropriated symbolic content and expose the egotistical self-interest and tautological claims to power behind its conventional use. This was very much the approach of the Berlin faction of the dadaists who utilized photomontage techniques “as a subversion of the myth of the photograph as truth.” This results in the reuse or re-deployment of existing constructs in a different value system, thereby demonstrating the implied symbolic meaning of the “acceptable”/mainstream/official sources. There is a naive/childish/insolent attitude of announcing publicly what is — from the viewpoint of the powerful and dominant — mutually agreed to be kept out of explicit public discourse. In this way it reveals the hidden foundations of power embedded in such practices and exposing them to discussion — and ridicule. What this accomplishes is the dissolution of the separation between levels. Rather than there being separate public and private views, they are merged and important positions necessary for functioning of the entire system cannot be hidden away from public scrutiny in a purely private arena.

As Mayo Thompson once put it in an interview:

“With this tension between revolutionary thought and revolutionary practice, there’s always a kind of contradiction. After a while I realised that for my own purposes the contradiction was in keeping with that Left idea, to jack up the volume of the contradictions. Make them sharper, make ’em deeper, make ’em tougher, make ’em harder, make ’em more real, make ’em more powerful, make ’em inescapable, undeniable.”

But he also added:

“Pop songs are really free-standing things, and they can be surrounded by other things which are unlike them. Life’s a jukebox. Programme it. Have fun.”

One of the fathers of the “New Left”, the western marxist C. Wright Mills was described as endorsing precisely the sorts of elements that ended up in this music by Michael Denning in his book The Cultural Front. Denning discussed the gradual break-up of the socialist “Cultural Front” in the mid-Twentieth Century and the eventual emergence of the “New Left” in its place, explaining how Mills advocated and endorsed a kind of synthesis of some of the otherwise antagonistic hack, commercial and avant-garde elements of the older Cultural Front in an effort to “repossess” cultural apparatuses (including media institutions). They key was to see artists as working with elements that are not entirely individualist and within their exclusive control. These sorts of concepts gained a lot of traction within the New Left movement. Mills’ comments very much look forward to the sort of music made by The Red Krayola.

Another reference point would be the work of Peter L. Berger and Thomas Luckmann, who wrote The Social Construction of Reality. Berger in particular was a political conservative who spent most of the rest of his career fighting against the use of his theories by the New Left. Though much of the theory became obsolete, in a sense, when the leftist French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu rose to prominence in the 1970s and combined a similar theory that revolved around the concepts of “habitus” and different kinds of “capital” (all formulated within a framework heavily influenced by Einstein‘s theory of relativity and Maxwell‘s equations), with novel quantitative/statistical methods. For that matter, Berger and Luckmann’s sociological theory ended up being slightly redundant with the work of French psychiatrist Jacques Lacan from the 1950s.

Just to drive home how this is typically a politically leftist approach to art and music, consider these words from V. I. Lenin‘s last article in Pravda before his death, “Better Fewer, But Better” (March 4, 1923):

“Indeed, why not combine pleasure with utility? Why not resort to some humourous or semi-humorous trick to expose something ridiculous, something harmful, something semi-ridiculous, semi-harmful, etc.?”

That is really quite close to the frame of mind needed to appreciate The Red Krayola’s music. There is much more than just the tiniest particle of the old in their music, but the the band certainly uses the ridiculous and the humorous to piece together something new and useful out of bits of the old. It is above all a battle for meaning. They wanted all new meaning. And they were building an aesthetic dimension out of old trashy musical elements!

These points rely upon a recognition of something often lost in ordinary discourse. Some people divide statements and beliefs into a binary classification of objective and subjective, with objective things being beyond or outside that of individual people and with subjective things being entirely in the head of individuals. But this is overly simplistic. There are also social constructs, which are socially determined beyond the control of any one individual person, but nonetheless are socially arbitrary and not “objective” scientific facts — this idea has a parallel in the so-called “Veblenian dichotomy” of institutional economics. It is precisely in this realm of “social constructs” that The Red Krayola’s music directed most of its effort.

The Red Krayola certainly weren’t the only musicians attempting something along these lines. Similar approaches appear in Brazilian Tropicália (Tom Zé, Rogério Duprat), psychedelic folk (Godz), some Krautrock (Faust), British Canterbury Scene rock (Robert Wyatt), certain indie rock (early Beck) and Hypnagogic Pop (Ariel Pink‘s Haunted Graffiti), and even avante garde composition (Charles Ives, Van Dyke Parks), etc. Of particular note is the fact that The Mothers of Invention were possibly the first rock/pop group to have dabbled in this, with inconsistent results. Mayo Thompson specifically credits Frank Zappa (of The Mothers of Invention) with being one of the first to employ this approach in the rock/pop music realm. Yet Zappa didn’t stick with the approach. Thompson stated in an interview,

“Zappa started off, and his records were handled as comedy, the labels that he dealt with. Zappa is like an analog for us in a certain sense. He also, I think, thought hippies were stupid and foolish, and kidding themselves, and congratulating themselves on how hip they were, but only by keeping their eyes closed, not noticing what anybody else was doing. At the same time, he recognizes that humor was one of his most powerful devices. But it ate at him to the point that he wanted actually to be taken seriously. So that became more important to him than anything.

“I would say that the difference between me and the people (from past underground rock movements) is that I have no commitments to any one form, or style, or anything else like that. I’m interested in music because it’s self-activating, to some extent. I’m interested in art — the democratic aspect of it. I don’t mean like, gee whiz, democracy, either. I mean like democracy as democratic expression of a sense of individual human beings getting their own crap together.”

When it comes to the music on Hazel, it is clearly an update on the style of God Bless the Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It. Mayo Thompson has said — maybe not entirely accurately — that every theoretical innovation he and The Red Krayola devised was already articulated in the 1960s:

“In terms of what passes for theory in music, with regard to material potential, I think I did all my theoretical work on musical possibility in the ’60s. The first five records sum up everything I ever had to say in theoretical terms.”

What is amazing is not the just the durability of the God Bless style, which still sounds ahead of the curve roughly three decades later, but that the band is able to use the same conceptual style while heeding the passage of almost thirty years worth of pop music. Hazel doesn’t rely on all the same bits of source music as God Bless the Red Krayola — though some things bear similarities, like the atonal, sing-speak female vocals (like the second tracks on each album: “Duck & Cover” here, “Music” on God Bless). There is much more emphasis here on easy listening music. That ends up being the crazy glue (pun very much intended) that holds all this together. There was an interview with Iman on some TV talk show long ago, and she discussed how her husband David Bowie would sing at home all the time. Though she corrected the host by saying that rather than his famous songs he would sing nonsense, just little mundane melodies. In other words, pure kitsch. That is precisely the kind of old musical source The Red Krayola mine on Hazel. It is evident on songs like “I’m so Blasé” and “Duke of Newcastle.”

From a process standpoint, these songs were built up through the contributions of the assorted performers in a way that resembled the surrealist exquisite corpse parlor game, in which a story is assembled by each participant sequentially adding something, usually only aware of the immediately prior contributor’s material rather than the whole. David Grubbs said in an interview,

“Frequently, it was like an exquisite corpse game where somebody lays something down, then somebody else overdubs on that, one at a time. Each song grew into these absolutely strange, collage-like creations.”

The band also followed a strictly collective approach. Regardless of who contributed what, every song is credited only to the entire group, collectively. Emphasis on specific individual contributions and hierarchy was discouraged.

A few of the songs here have start-stop structures, without any sort of syncopation (just as on God Bless) . “Decaf the Planet” and “5123881” are examples. Though this shows up in parts of other songs too (“GAO,” “Boogie,” etc.). On the other hand, some songs are built principally around grooves and repeating riffs, like “Larking,” “Hollywood” and “Another Song, Another Satan.”

The use of folk music elements is something new for The Red Krayola. “Falls” has a banjo solo. There is a fair amount of acoustic guitar throughout the album too.

Hazel is one of The Red Krayola’s finest albums. It delivers (serious) lyrics about leftist politics with (unserious) cartoonish vocal affectations, and dissembles and adds noise to old musical elements that aren’t as politically neutral as they seem. This is above all music that gains meaning from dynamic movement. Any one element might be subject to multiple interpretations, and the movement in the context of the songs and album as a whole make clear that meaning is flexible, relative. The Red Krayola do their best to fashion a utopian leftist vision of a vaguely classless society where musicians can do whatever they want, and fashion their own meaning.