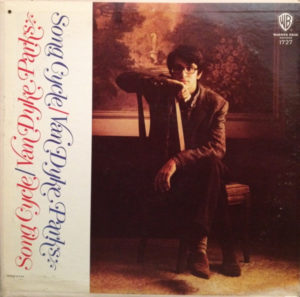

Van Dyke Parks – Song Cycle Warner Bros. WS 1727 (1967)

Van Dyke Parks is a notable fringe figure to fans of oddball pop music. He was associated with a number of popular and notable artists, like The Beach Boys, Harry Nilsson, Frank Sinatra, Ringo Starr, John Cale, Joanna Newsom, etc. He works out of Los Angeles, and in that barren wasteland of serious culture, he was always an eccentric standout. He never really had any widespread popularity as a solo artist, but his contributions to popular works by others (The Beach Boys and Joanna Newsom loom large here) are probably why most who have heard of him know about him at all.

Song Cycle is less a work of popular music than it is composed “classical” music in the spirit of Charles Ives, who blended Euro-classical, hymns, folk, pop and more into idiosyncratic and innovative compositions. Parks simply updates the pop culture reference points — somewhat. He also draws from Tim Pan Alley, ragtime, vaudeville, bluegrass, marches, and an assortment of old-timey musical forms long since passed from popular favor. There is particular emphasis on the music of the Great Depression era, and all things uniquely American, especially Californian. This was an anti-Anglophile stance in the midst of the so-called “British Invasion” period. It also took high-brow forms of composition and places them into service of more low-brow forms. It was a serious approach to un-serious music. Parks adopts cliché/kitsch but re-contextualizes it, in an approach highly similar (in form, though not in substance) to that of the tropicalistas in Brazil around the same time. It is something of a natural — if impertinent — way to try to break out of imposed restrictions.

The characteristic Parks song jumps from one style to the next, emphasizing the cuts, contrasts and juxtapositions as much as any of the disparate styles he adopts. Any one approach hardly lasts more than a few seconds, before there is some kind of transition to something else. But as to those styles, there are many, and he’s obviously a good student of all of them. He’s even better at deftly making the transitions between the varied passages into something that doesn’t seem completely unnerving — a little perhaps, but that is entirely intentional and necessary, even, to giving this an impact. Yet for all the formal objectives and technical aptitude, Parks saves plenty of room for humor. Usually that gets lost in a work this complex and difficult to execute.

This was a lavishly produced album — the budget was more than three times what was typically allotted to a pop album at the time. Though it sat for about a year before the record label released it, and then commercially it was a flop. Many listeners fault Parks’ vocals, which aren’t much of an attraction but also aren’t entirely bad. The other frequent complaints would be coyness, lack of prettiness, willful over-complexity, ostentatious-ness, impenetrability, messiness, … this list goes on. Song Cycle may well be all those things. But it also is a very bold in its experimentation and earnest in its admiration for its sources of influence, trying to accomplish a lot without becoming arrogant. As Parks later said in an interview, “You can exalt what is humble.”

For sheer daring ambition, there aren’t all that many albums of the era (or any others) quite like this. In fact, probably the most inspiring thing about the album is how absolutely unlikely and improbable it was and is. It would be wrong to call this a perfect album. But, looking back, it is one that was headed in a good direction, even if few followed along.