There is a frequent accusation that Elvis Presley was racist — or appealed to racists, or some such similar accusation. Rappers, from Chuck D of Public Enemy to Mos Def to others in hip-hop have taken pot shots at Elvis along these lines — some of those statements later retracted. But is there any merit to this claim? It is a thorny issue, and whole books and more have been written on the intersection of Elvis and race.

One of the defining characteristics of Elvis’s life and career was the particular time period in which he lived and worked. The “glory years” of Elvis’ fame coincided exactly with the post-WWII boom, when a consumer lifestyle was extended more deeply into the American population that ever before (or since). Elvis was, in some ways, made out to be a champion of the ordinary salt-of-the-Earth working man. And yet, the post-WWII boom was limited to white people, and especially to white men (women benefited primarily through marriage, not through workplace participation). As Alan Nasser wrote:

“A rational and historically informed response to the legend of the middle class is that this alleged stratum of the 1920s and the [post-WWII] Golden Age existed for a mere 34 years of American history. Before the 1920s just about all working-class peo[p]le were poor. Since 1974 then we have had 42 years of burgeoning inequality, un- and underemployment, growing poverty and steadily declining wages with no end in sight. The middle class was a departure from the historic norm of a materially insecure working class, the default position of industrial capitalism.”

Notice how the 1974 decline of the working class coincides almost exactly with Elvis’ post-1972 decline? This is not to mention how Elvis’ rise to stardom starting in 1954 at Memphis’ Sun Records coincided roughly with the beginning of the post-WWII “Golden Age”.

As most rejoinders to the “Elvis was racist” claim lay out — as with biographer Peter Guralnick‘s noted essay — Elvis should not be seen as a cultural pirate, appropriating black music for the benefit of white men. Elvis had a deep and abiding respect and admiration of black music, from gospel to R&B and more, and often quite humbly expressed his debt to that music publicly.

The real gripe tends to be an economic one: as a symbol of post-WWII prosperity that was denied to most black people, Elvis became a symbol of “racial” inequality, despite the way his music appealed to an ersatz kind of economic equality among his white fan base. The real question is whether it is fair to pin this on Elvis. Just as the punk/oi band Sham 69 was saddled with a skinhead/neo-nazi fanbase that they actively opposed, what responsibility does Elvis bear in this context? Is it really the “structural racism” of society at large, or even of critics that is to blame instead?

As Alan Nasser notes:

“The matter hinges on what is meant by ‘middle class’. This is no ‘merely’ semantic question. The term is at the core of the justification of modern capitalism, and connotes not merely a statistical income level, but is meant to convey the relation between one’s willingness to earn a living, i.e. to work hard, and the possibility of achieving a desirable standard of living as a reward for one’s work. The example above, describing the benefits available to the one-breadwinner family during the Golden Age, is meant to imply that those benefits are the just deserts of hard work. *** The middle class gets what it deserves as a reward for its labor. But the truth is that the working class has never been able to achieve economic security on the basis of its wage.

Being dutifully productive has never been sufficient to guarantee the worker a satisfying life. *** More precisely, the benefits might be forthcoming — remember, hard work is merely a necessary, not a sufficient, condition of material security…”

This is the issue raised decades after Elvis’ death by pop singer Nicki Minaj, who, in one writer’s estimation, “refus[ed] to apologize for wanting to be visible and rewarded like her peers”. (One can set aside the sheen of presumptuousness in self-selecting one’s “peers” to be the most famous and highly compensated entertainers in the world).

One way to approach the question is to ask how Elvis was involved in movements for racial equality. The answer is that he wasn’t, at least not in an explicitly political way. Rather than activism for equality, Elvis — especially in his early musical career in the mid-1950s — represented a cultural shift that denied the premise of racial segregation and Jim Crow laws. He, along with others, advanced a music vision that was simply incompatible with racial segregation — a “deterritorialization” or hybridization if you will. Yet, in the post-Jim Crow era, with de jure segregation nominally overcome, Elvis’ contributions to cultural awakenings were rather muted, at best. In a way, the Freedom/Civil Rights Movement in the United States revealed that formal repeal of the Jim Crow segregation laws was really not the whole problem. And, for that matter, the way that Elvis’ career took shape after his stint in the army, with “Col.” Tom Parker managing him through B-movie deals and other crass commercial moves, revealed some of the problems that remained depressingly intact despite Freedom/Civil Rights Movement victories to end legal cover for lynchings, improve educational access, gain formally unencumbered voting rights, etc. Blacks may have achieved some of those things, at least nominally, but they still lacked the sorts of power and wealth that white males enjoyed, and so many of the freedoms won in the 1960s were emptier than hoped. It was in this context that black militancy emerged, with the so-called black power movement. As those activities started to make tangible gains, the backlash was brutal. Elvis had no part in that story.

Bob Dylan gave an interview where he said,

“I think of rock ’n’ roll as a combination of country blues and swing band music, not Chicago blues, and modern pop. Real rock ’n’ roll hasn’t existed since when? 1961, 1962?”

He added,

“And that was extremely threatening for the city fathers, I would think. When they finally recognized what it was, they had to dismantle it, which they did, starting with payola scandals and things like that. The black element was turned into soul music and the white element was turned into English pop. They separated it.”

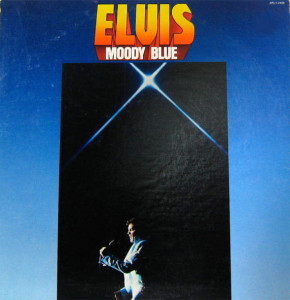

The soulful, gospel-inflected sounds of Elvis’ early 1970s second peak retained some elements of both black and white culture. But the “city fathers” that Dylan referred to were there in the audience. Meanwhile, at the 1972 Wattstax music festival Jesse Jackson (before he became a collaborator with the system he condemned) gave his memorable “I Am Somebody” speech. If it still needed to be said that black people were “somebodies,” then the triumphalist quality of Elvis’ post-comeback music could be seen as a bit premature from a black perspective.

Historian Jefferson Cowie, in his book Stayin’ Alive, described some popular musicians of the 1970s as being ambivalent about a status quo that privileged white males over women and racial minorities. It is a criticism not unlike Hannah Arendt‘s famous phrase about “the banality of evil,” something that reflects what some academics call “structural violence”or “systemic violence” — the everyday violence of an unjust social system inflicted without conscious malice by participants. Elvis would therefore be “racist” if he failed to think about his role in such a system. This might pinpoint the critiques of Elvis as the alleged racist. The rebuttal would be the this makes Elvis a scapegoat, singling out one individual for something he took no conscious part in and perhaps ignoring similar conduct by others. It must be remembered, too, that Elvis was not highly educated and was neither particularly intelligent nor savvy, which is why he (notoriously) ceded so much control over his career to his manager “Col.” Tom Parker. Perhaps the criticisms of racism should be better leveled at Parker for steering the star in certain ways?

It bears repeating that despite his great wealth (though he was quickly depleting that wealth by the time he died), Elvis never owned the “means of production” (and especially not the means of distribution, etc.) and remained an entertainment “worker” his whole life. He also came from humble working-class roots, and those who try to paint him as a racist might be using him as a scapegoat for what is really an elitist, anti-working class agenda. After all, does anyone blame workers who earn a living within an exploitative capitalist system? Here, it is worth avoiding the “beautiful soul” syndrome by which people insist on existing separately an apart from the corruption and evil of the world — something that is really a strategy of exerting moral superiority that depends on maintaining the existence of the condemned corruption/evil. Even as he became wealthy and was dubbed the “king of rock”, it is possible to view a king as a tragic figure confined by his position.

Furthermore, there is a weird “identity politics” aspect to many of the accusations of racism hurled against Elvis. Often these accusers point to Elvis’ “structural” superiority making his action inherently suspect of racism. But the problem with this strategy of the accusers is this: “Its exclusive focus on structural weakness enables it to play its own power game, ruthlessly using structural weakness as a means of its own empowerment.” In this context, that the “accusations are very problematic if not outright false, etc., [is] dismissed as ultimately irrelevant.” Someone like Elvis is more or less automatically suspected of at least being a white supremacist, a cultural pirate, and guilty of racial insensitivity, and the accuser’s position of structural weakness gives her or him the power instead — a kind of valorization of victimhood status in which only victims can testify and accuse, as if victims inherently lose all ressentiment and are somehow purified “into ethically sensitive subjects who got rid of all petty egotistic interests.” “We thus enter a cruel world of brutal power games masked as a noble struggle of victims against oppression.” This is the seedy and almost paradoxically segregationist underbelly of the position of the “beautiful souls” who crusade against Elvis’ supposed racism. In this sense references to “structural” racism end up as false flags that distract from what is really the pursuit of an ignoble individualist agenda, which suggests Elvis (as an individual) somehow represents the make-or-break difference between a structurally racist or just society, and in which the accuser individually benefits (psychological or otherwise) from claiming to triumphantly reveal racism in what appears to be a race-neutral situation.

In the final analysis, Elvis was instrumental in fostering black/white integration in the United States at a time before that seemed inevitable. He wasn’t a political activist though. Did he have an obligation to be one? Maybe, along with a host of other obligations to not hoard wealth and opportunities in the entertainment industry. But by the end of his life his fortunes were significantly depleted. It is asking perhaps too much to say that Elvis should have been out front in every progressive social movement that occurred during his lifetime. There was nothing consciously racist about Elvis in the available historical record, though from another perspective he was a rather obedient participant in an entertainment industry that included substantial racism and he perhaps failed to adequately think about his role in the continued oppression of blacks and other minorities from the late 1960s onward, thereby failing to actively distance himself from those things (and sexism, etc.) when he had the wealth and power to do so.