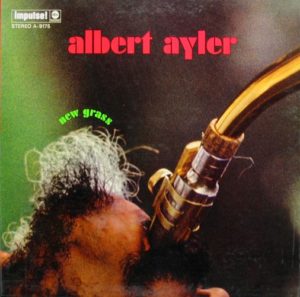

Albert Ayler – New Grass Impulse! A-9175 (1968)

A divisive album from a figure who seemed divisive in other ways from the start. Ayler rose to some level of renown among jazz heads as a pioneer of free jazz. But he got his start in R&B bands, and New Grass is an early attempt, of sorts, at jazz/R&B fusion. The album opens with typical Ayler free jazz wailing, then a brief spoken introduction, in which he states with radical earnestness that he hopes listeners like the album, and then it is on to the real surprise: R&B tunes laced through with solos far more skronky than any sort of King Curtis or The 5th Dimension mainstream R&B/soul track. The real problem with the album is how it gets going. “Message From Albert/New Grass” implies the album is something other that what it turns out to be — some kind of misguided attempt to ease listeners expecting “conventional” free jazz into the album. But “New Generation” and “Sun Watcher” really do get the album going, with great grooves, shimmering keyboards (on the latter), and what are actually smoking performances on sax by Ayler. Everything finishes strong with the sublime rave-up “Free at Last” too. But it is hard not to think that the album would have been much improved by dropping the first track and squeezing in the outtake “Thank God for Women” (posthumously released on the Holy Ghost box set). Anyway, while the album sequencing is too awkward to be entirely successful, this album deserves much credit for its radical concept alone. Jazz, and free jazz especially, was generally a pretty elitist musical form by the late 1960s, while lite R&B/soul was on the complete opposite side of the spectrum, with more plebeian appeal. Ayler throws them together without any regard for the social distinctions erected between those highbrow/lowbrow genres. While Miles Davis gets more credit for his approach to jazz/rock fusion, it is worth keeping in mind the way Miles leaned on esoteric and elitist forms of rock (not to mention the work of avant garde European composers). So, while some people saw this album as Ayler selling out to commercial tastes, a different, perhaps better, way to look at it is as an attempt to transcend the social confinement represented by narrow genre categories. And Ayler approaches that challenge with his usual open-hearted, emotive, and guileless version of what everybody typically expects to be purely cerebral, technically and conceptually challenging virtuoso performance. Contrary to its reputation, New Grass is slowly gaining more currency as a pretty decent album. It isn’t Ayler’s best. Yet it works. Anyone who does dig this should also check out Archie Shepp‘s similar effort For Losers.