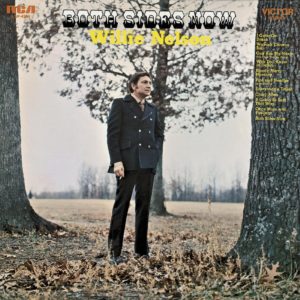

Willie Nelson – The Hungry Years Sony Music Special Products A22354 (1991)

The Hungry Years — not to be confused with a budget-priced compilation album from the early 1980s by the same name — is one of the most obscure albums in Willie Nelson’s vast catalog. The original sessions were in 1976 at Studio in the Country, located in between Bogalusa and Varnado, Louisiana. There were overdubs in 1978, then the tapes were shelved. They were found in a deteriorated state in the late 1980s, restored, and then further overdubs were added in 1989 and 1991. Amidst Willie’s troubles with the IRS, he negotiated the release of The I.R.S. Tapes: Who’ll Buy My Memories?, of which a significant portion of the sales were committed to his tax debt (which was mostly accumulated interest and penalties, actually). The I.R.S. Tapes needed to go multi-platinum in order to cover the tax debt, which was overly optimistic. It was sold by mail via 1-800 telephone numbers, supported by TV ads. Starting around June of 1991, The Hungry Years was offered to callers as an add-on. It is not clear that The Hungry Years was ever advertised aside from being mentioned to people calling the 1-800 numbers seeking the I.R.S. Tapes album. But The Television Group, the Austin, Texas company running the telemarketing, went into bankruptcy, and by February of 1992 the 1-800 numbers were shut down. While The I.R.S. Tapes was eventually made available in regular stores, it does not appear that The Hungry Years was ever sold through conventional channels like brick-and-mortar music stores. So that means this album was only ever commercially available for less than a year, and even then only through an obscure call-in mail-order program. Some discographies neglect to even mention that it exists.

The sound of the album falls somewhere between Sings Kristofferson and To Lefty From Willie. The songs draw from the likes of Neil Sedaka and Paul Anka. These were respected songwriters at the time, and even Elvis covered Anka’s “Solitaire” around this time. Their songs have not aged all that well, though, because they fit too comfortably into the mold of being laments of the white patriarch dealing with having to be an “individual” after second-wave feminism and the decline of trade unionism. Overall, there are also a few too many little curlicues and other ornate features added to the music here. It might be the overdub sessions — not one, not two, but three — spread out over 15 years that contribute to that, but Willie’s own contributions are partly to blame as well. His vocals are a little overwrought sometimes, with too much vibrato and too often forced into the upper register of his vocal range. Though even guest Emmylou Harris does the same on one song (“When I Stop Dreaming“). He does add some interesting guitar solos on Trigger. His sister Bobbie gets a good amount of time in the spotlight, which is nice.

There are all sorts of good bits on this album. The biggest problem is that those good bits don’t ever come together in any unified and coherent way. They just float around among more dubious elements and arrangements that are a bit off. For instance, the 1989 overdubs add a horn section — one of the only times one of Willie’s albums tried to recreate the style of Shotgun Willie. But Shotgun Willie had horn arrangements in a classic soul style. These are merely passable approximations. The most sympathetic performance is probably the last song, “Carefree Moments.” But the song itself is not particularly well-written, and a good performance can’t remedy that problem. So this album always threatens to be really good, but seems to consistently fall short.

This rare album is no lost classic. Yet considering the sorry state of so many of Willie’s albums from the 1980s and early 90s, this was certainly better by comparison.