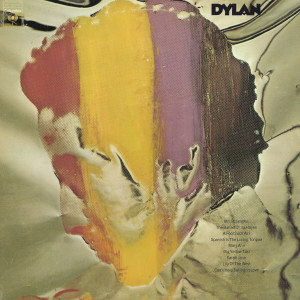

Bob Dylan – Blood on the Tracks Columbia PC 33235 (1975)

In a way, isn’t this album everything that New Morning failed to be? What I mean is that New Morning always seemed like Dylan trying to sound contemporary and relevant by making overtures to the California singer-songwriter movement. The problem was Dylan didn’t really fit well into that genre (even if he had moved to Malibu). Blood on the Tracks turned things around and had a more bitter and angry tone, more stripped down instrumentation, more of a narrative lyrical approach, and less demands on Dylan’s limited vocal abilities. The newer approach suits Dylan a whole lot better. One thing that is striking when comparing these two albums is that New Morning seems like it is trying to be personal, while Blood on the Tracks seems like it can’t help being personal. The latter is far more compelling.

Dylan’s marriage was headed for divorce when this album was recorded. That says volumes about the subject matter. These are break-up songs. The protagonists seem hurt, recently, and still hurting. These songs speak from a place too close to the pain to be past or above it. Was the whole relationship wrong from the beginning? Who caused it to go wrong? Who was to blame? Him? What will he do know? Dylan had relocated to California a year earlier, but this music was a return, or sorts, to the kind he had made back in New York, before the move, before things kind of fell apart. He’s looking back to make sense of the past before moving on into the future. There is catharsis at work here.

This isn’t the kind of album that makes for easy listening, at least not on any kind of regular basis. It’s rather surprising it was so popular. But it is a success, and perhaps the last really great album Dylan would make. One of the essentials of his storied career.