Tom Waits – Mule Variations Anti- Records 86547-2 (1999)

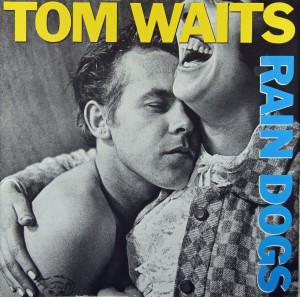

Waits’ late-90s “comeback” album has aged well. After the achievement of Rain Dogs in the mid-80s, and Bone Machine in the early 90s, he largely slipped from view for a few years. His comeback positioned him as something of an elder statesman of the independent rock scene, which still had some vitality even as major labels had already started to consolidate their investments around a fairly narrow range of music that excluded stuff like this.

When David Bowie had mild resurgence a couple years prior with EART HL I NG, he seemed to draw his subject matter from watching movies on TV. Although Bowie and Waits go in much different directions in terms of genre, and only Waits leans on the use of humor, Waits’ lyrical focus has shifted to more middle-aged circumstances as well here too. Take “Come on Up to the House,” which might be viewed as one of the best rock songs about a dinner party. The lyrics, which cajole someone loaded with excuses to come over for a visit, have some great turns of phrases (like about coming down from that cross because we could use the wood). It also features orchestration that recalls the album-closing style of “Anywhere I Lay My Head” from Rain Dogs or, reaching back further, “Cripple Creek Ferry” from Neil Young‘s After the Gold Rush. As Harry Nilsson once did so well, “Cold Water” also evokes the mundane aspects of daily life, like taking a shower. And “What’s He Building?” is an eerie rock monologue in the tradition of The Velvet Underground‘s “Lady Godiva’s Operation” but with a neighborly suspicion narrative like that of the Tom Hanks film The ‘Burbs. Sure, Waits had released “In the Neighborhood” on Swordfishtrombones, but the irony of that song in muted if not absent here more than fifteen years later.

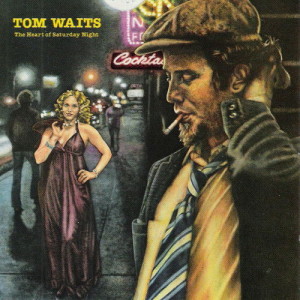

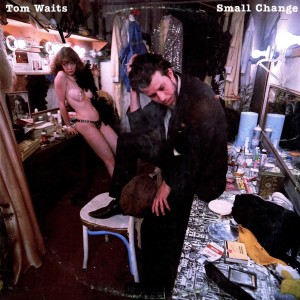

At the time the album came out, “Hold On” was the single, and it met with success. It hearkens back to the sentimental (and sometimes maudlin) side of Waits’ music—think “Tom Traubert’s Blues (Four Sheets to the Wind in Copenhagen)” from Small Change, “Ruby’s Arms” from Heartattack and Vine, and “time” or “Blind Love” from Rain Dogs. This is something that appears elsewhere on the album too. Yet this is a softened, more mature sentimentality that stops just short of being truly maudlin. These songs work well here. The opener “Big in Japan” also tended to be liked by audiences. It has a heavier beat and more rock and roll edge to it, with some gruff histrionics. While these are solid songs, the album as a whole has much more to offer. It is really the more mature, middle-aged attitude (Waits was nearly 50 years old when it was released) that shines through in hindsight. It lacks nothing in terms of relevance and appeal to listeners of all ages.

Maybe surprisingly, this is really one of the finest full-length albums of Waits’ entire career, all told. He continued to put out some decent music later on but despite some nice highlights it was not as consistently solid at album length.