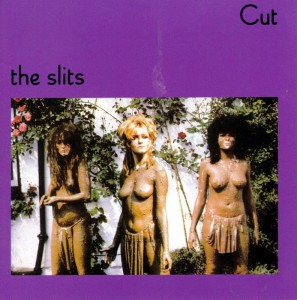

The Slits – Cut Island ILPS 9573 (1979)

The Slits did heroic things. Cut is empowering. Songs on this album celebrate whatever the group loves, brushing past hard times with mere innuendo along the way. Pushing long bass lines from Tessa Pollitt that are louder than anything else and totally funky, the scratchy, sharp, staccato guitar of Viv Albertine comes laced over the top (with a dissonant, atonal sound Albertine frequently described as “oriental”), The Slits’ sound can’t be mistaken for any other. And that is even without mentioning the Teutonic vocals of Ari Up (at times billed as Ari Upp), who didn’t so much sing melodies as warble slogans along with the rest of the music. The Slits keep things interesting. They even manage that by doing as little as adding piano and shifting the rhythms on “Typical Girls.” All those little things sound so much more spectacular when set apart as they are on Cut. But in the big picture, there is nothing little or ordinary about The Slits.

Cut is pretty radical music. The band paid a price for it. Ari Up was stabbed twice! But they fought on because they believed in what they were doing. Central to their project was the idea that there should be space in music for every sort of viewpoint. That meant women should have a voice in rock and punk, forms dominated by men. In later tours, the band would listen incessantly to Sun Ra‘s Space Is the Place (they even tried to visit him in Philadelphia when on tour, but he happened to be away touring at the same time) and Don Cherry‘s Brown Rice. They loved Ornette Coleman too. Albertine liked Yoko Ono as well. Get the picture? All these artists shared something in common: a fiercely individualist streak that insisted that society should tolerate a lot more variation than found in its contemporary history. And they all fought battles to create room for their music. Ornette was physically assaulted in his early career because people found his music so shocking. It was the same with The Slits. Yet they were willing to fight for what they believed in despite these burdens. They did something to try to change the world. And didn’t they, in a little way?

The Slits were formed in 1976, when Ari Up was a mere 14 years old. Kate Korus was their original guitarist, but the Australian-born Viv Albertine took over on guitar early on. Albertine was already a fixture of the London punk scene, but had only a few months playing guitar before joining the band. She was available to play after being kicked out of The Flowers of Romance. Palmolive (born Paloma Romero) was their original drummer, but Albertine forced her out just before the band signed to Island Records to make Cut. One of Palmolive’s songs, and others with at least her lyrics, makes the album. She insisted that her close friend Tessa Pollitt sing her “Adventures Close to Home,” rather than Ari. They temporarily brought in drummer Budgie (born Peter Clarke) for the album and limited touring. He was under specific instruction to play a little like Palmolive, pounding toms and riding the hi-hat without ever doing big cymbal crashes.

Of the core original band members, only one was born in England, and two (including the singer Ari) spoke English as a second language. These were kids born after WWII, and most of the bandmembers came from families of divorce, raised by single mothers. In her memoir Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys, Viv Albertine said about the punks:

“we’re the children of the first wave of divorced parents from the 1950s, we’ve seen the domestic dream break down. It was impossible to live up to. We grew up during the ‘peace and love’ of the 1960s, only to discover that there are wars everywhere and love and romance is a con.”

This puts The Slits’ feminism — more on that in a moment — in a certain light. The punks were often disillusioned with society. But coming from families of divorce can give children what scientists called “stress inoculation-induced resilience.” Anyway, whether it is that or not, these girls chucked out the expectations of what was considered “normal” or “proper” and undertook the difficult task of forging their own meaning. Like the other punks, they adopted a uniquely urban approach to music, with scratchy, industrial guitar sounds, and electrified instruments. Unlike the hippies of the prior decade, they struck a more impertinent, shocking pose. Hunter S. Thompson wrote about “the grim meat-hook realities that were lying in wait” for anyone who took Dr. Timothy Leary’s “turn on, tune in, drop out” consciousness expansion ideals too seriously back in the 60s. The punks saw those meat-hook realities and confronted them, like a counter-counter-offensive.

The Slits circulated with most of the original wave of London punk bands. “So Tough” was written about Sid Vicious, and “Instant Hit” about Keith Levene. Viscous was in the band The Flowers of Romance with Albertine before joining The Sex Pistols. Levene, later of PiL, was a longtime friend of Albertine’s and helped her learn to play her guitar. “Ping Pong Affair” was written by Albertine about her on again, off again romantic relationship with Mick Jones of The Clash. The few songs about the UK punk scene are just part of the story though.

Ari Up was the band’s frontwoman, but she was simply too young to run a band. It was Viv Albertine who organized things and made the band function. Ari is still a real presence. She was heavily into dub and reggae. The whole band was too, but her even more than the others. She brought that to the band’s sound in time for Cut — dub and reggae have no bearing on their 1977 session for radio DJ John Peel released as a 1987 EP. It helps that reggae producer and musician Dennis Bovell produces Cut. He draws out the best in the band, and perfectly captures their musical vision (he also plays “percussion” with a box of matches, a spoon and a glass on one song, “Newtown”). Ari sings in a way that swings wildly between styles and registers. She hisses and screams. She also had an inimitably sarcastic German drawl that seems incompatible on a basic level with anything stuffy and pretentious (a quality somewhat like Marc Bolan of T. Rex or Bryan Ferry of Roxy Music but even more flamboyant). Though despite her biting sarcasm she largely avoids the seething rage and harshness of tone of most other (male) punk vocalists. She sings high trills, then chants in lower registers — something vaguely similar was common in black gospel music, but not in punk rock, or any other kind of rock. She came across as completely uninhibited. Her unsettling accent and fearless, childlike attitude are a big part of why The Slits’ irreverent humor works so well.

“Typical Girls” was a single, and a great one (paired with a cover of “Heard It Through the Grapevine” not included on Cut). Albertine wrote the song for the album just prior to recording. She got the idea and the title from a sociology book of the same name. It is laced with feminist concepts. No doubt, The Slits had a militant feminist stance. The album cover with them half naked covered in mud (they wanted to recreate an African tribal look, and appear like warriors) is often cited as an anti-feminist stunt, but it only takes a listen to the contents of the album to see that they were indeed feminists. They weren’t perfect, and their strange, spastic musical vision won’t be everyone’s idea of what they would be listening to in a better world. But the point was that their music expanded the possibilities, for women in rock and everyone else. And this was definitely a new configuration of sounds: groovy and oddly catchy while also unpredictable, edgy and discordant. The song opens with Pollitt laying a thick bass groove and Albertine strumming out sort of a superhero cartoon or spy movie melody, and Ari chants lines like, “Don’t rebel.” There is a break in the guitar part, and a piano figure pounds out a consonant rising and falling melody. Then there is a sharp break in rhythm, with the guitar playing Jamaican ska upbeats and a new bass line. The song manages to convey shifts in perspectives from lolling about in sarcasm to uplifting rising progressions that almost seem to earnestly look at the “typical girl” as having a valid existence too. The song continues to shift around, never settling down.

The framework of the song “Typical Girls” fits somewhat with the work of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who published his monumental book La distinction the same year Cut was released. Bourdieu elaborated on his concept of “habitus”, as a set of unconscious predispositions and social orientations that foster the reproduction of social hierarchies across generations. The Slits’ song asks “who invented the typical girl?” But this mocking rhetorical question is answered, partially, with the lyric, “Typical girl gets the typical boy.” Typical girls and typical boys go together, as if neither one exists or has meaning apart from the context of the pairing. The song portrays the dispositions of the “typical girl” (or typical boy) accumulated over a lifetime, not consciously, exactly, that just seems to go on, uncritically reproducing more typical girls (and boys). The Slits stood for snipping the Gordian knot of these dispositions. The song’s abrupt transitions and odd juxtapositions make it difficult to ignore them. And once they are recognized, it becomes had to justify them as anything more than arbitrary limitations.

“Spend, Spend, Spend” was written about a lottery winner Viv Nicholson (the song title cribbed from newspaper quotes and headlines about the winner). But it engages consumerist culture on a direct, personal level too. The song is partially a confession of addiction to consumer fetishism. The song doesn’t claim the band stands apart. Singing about it, though, is an effort to get past it. “Shoplifting” is the flip side to consumerism. The song accepts that material things are needed, but the guilt of want is simply discarded.

Palmolive’s “Adventures Close to Home” closes the album. The words are great: “Don’t take it personal, I choose my own fate / I follow love, I follow hate.” This encapsulates The Slits’ politics quite well. Yet with Tessa singing and Ari Up playing bass, and without Palmolive to unselfconsciously bang on the drums, the performances don’t have an optimal touch. Palmolive’s recording of the song with her next band The Raincoats is superior. But, Palmolive insisted that Tessa sing as a condition for the group to record her song.

For all the edgy, odd, confrontational sounds on Cut, the music also has a softer side woven throughout. The band was listening to Dionne Warwick‘s Dionne Warwick’s Golden Hits – Part One incessantly around the time of the recording sessions, in addition to things like David Bowie‘s Low. Smooth pop soul phrasing is present in this music nearly as much as atonal noise, funk and reggae beats, and sudden shifts in rhythm and tone.

There were a handful of other UK punk bands that incorporated elements of reggae and dub and funk into their sound. Few did so as brashly as The Slits while still keeping a bright sense of humor. Even more than three decades later this music sounds fresh and original.

Also, here’s a link to an excellent review of the album by Anthony Carew.