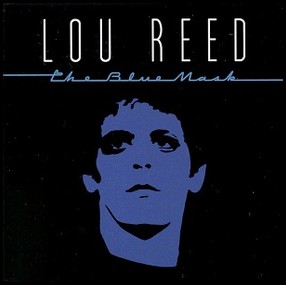

Lou Reed – The Blue Mask RCA Victor AFL1-4221 (1982)

Well, Lou Reed’s career has covered as much territory as anyone else’s in rock. The Blue Mask renewed his critical cachet in the early 1980s. Frankly, it is executed flawlessly. Robert Quine adds some scorching guitar to bolster Reed’s occasionally humdrum fretwork. Let’s face it, Reed was always a risk taker on guitar, but he was hardly ever more proficient than a thoroughly average rhythm guitarist, sort of rock’s equivalent to baseball’s utility infielder. But Quine was willing and able to deliver plenty of explosive guitar excursions, as best summed up by the unrelenting, jaw-dropping abstraction of his solo that concludes “Waves of Fear”.

So if there are complaints to be heard bout The Blue Mask, they have to be about the concept. And what of the concept? Basically Reed takes up the challenge he more tentatively presented on earlier works of making a middle-aged rock album. Conventional wisdom is that rock and roll is a young person’s game. The Rolling Stones touched on the issue with Jagger’s “It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll,” which reviewer BradL describes as “a song about the relationship between the musician and his audience, and the inevitable gap that arises as he gets older and his audience stays young[.]” Well, truthfully, that’s just one possibility. The “other path” is for the aging rocker to change, and essentially leave behind “rock” per se in favor of more of a sophisticated pop sound, to wit Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds and others. But Reed’s version of middle-aged rock will have nothing of the latter. This is rock. His lyrics are about domestic life and ordinary concerns of life in Western Civilization. But those lyrics are as much about contentment as fear, uncertainty, and disturbing undercurrents running through everything else.

Lou Reed is certainly writing about what he knows. The casual autobiographical style of so much of this album attests to that, like his expressed adoration for his writing, his motorcycle and his wife on “My House,” his supposed worries about crime waves in the streets on “Average Guy,” and the emotional outpouring for then-wife Sylvia on “Heavenly Arms.” But honesty and the act of conveying something that the artist knows are not enough, else any self-indulgent claptrap would pass for something special. It doesn’t, unless it touches on something elemental and grand, something lasting and universal. It is there that almost all argument with this album lies. Something serious and lasting is here, if you are willing to accept it. The psychiatrist C.G. Jung postulated “individuation” as the process of maturing to where a person is conscious of both the personal and collective unconscious. In a practical sense individuation is about accepting and resolving supposed contradictions, and about assimilating opposite characteristics. Jung’s genius provides the key to this album really. But because individuation rarely starts before you are in your thirties, if it ever starts at all, it is no wonder that the standards of youthful rock and roll hardly seem to apply to something unmistakably middle-aged.

If you reject what you just read, you still probably fall into the camp where you can appreciate some of the harder stuff here like “The Gun,” “The Blue Mask,” and “Waves of Fear” just for its drive. But to really get behind this whole motherfucker, it takes some kind of appreciation for the notion that purely adult themes have a place in rock and roll. Not everybody will agree with that premise, but The Blue Mask is one of the better arguments for it.