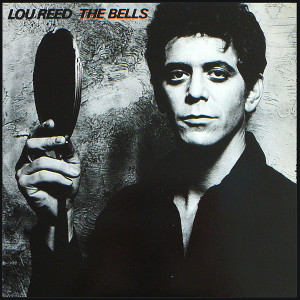

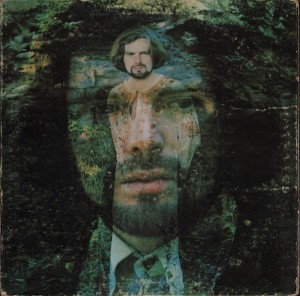

Lou Reed – The Bells Arista AB 4229 (1979)

Named after the Edgar A. Poe poem, The Bells is a cerebral album with a soft touch — unlike so much of Reed’s other work.

The way Reed recorded The Bells (with a quickly defunct technology) definitely sounds like something from the 1970s. It sounds like it has an inbred echo. Hearing it feels a bit like sonic vertigo, if vertigo was a pleasant feeling. The album does open itself up, though, after you get a sense of it.

“I Want to Boogie with You” has the old time sentimentality of Springsteen but more depth. Reed recants stories of family life. He doesn’t feel compelled to make it a pretty picture though. The dysfunctional “Stupid Man” or the vaguely autobiographical “Families” mark the arrival of a changed songwriter. On “Families,” he shakily cries “momma” as Lou Reed brings his struggles for transcendence to new contexts. He still had a passion of old fashion rock and roll, but was tackling that with a renewed energy. This makes up-tempo rockers like “With You” a natural environment for Reed, as well as for his band that previously backed Alice Cooper.

Reed’s lyrics over the years changed contexts but always retained core themes. His music, however, varied widely. The Bells teams Reed with the legendary Don Cherry, who co-wrote “All Through the Night.” Cherry is quite effective playing with a Harmon mute on “City Lights,” a tribute to Charlie Chaplin. The irrepressibly charming trumpet toots recall so well Chaplin’s Little Tramp. The lyrics, “Don’t these city lights/ bring us together?” are very worthy of being called Chaplinesque. The improvisational closer, “The Bells,” wants to be wrong, to fail, but Cherry turns out a baffling, lingering success of a song in just a few notes. Cherry always did play well in a rock context, as was certainly clear a few years later playing with his stepdaughter Neneh for Rip, Rig & Panic.

“Disco Mystic” with only two words worth of lyrics is sharp commentary on the vacuousness of the genre, even if disco commentary (good or bad) is of marginal interest. Fortunately, the plain groove of the song will never fade away.

The Bells is dense in sound and content. The whole thing is legitimate. It’s ambitious. Despite years of writing, recording, and performing Lou Reed still uncovers a wealth of inspiration. The album jacket too, with Reed gazing away from his reflection in a mirror, is a fine indication what might be his least indulgent work.