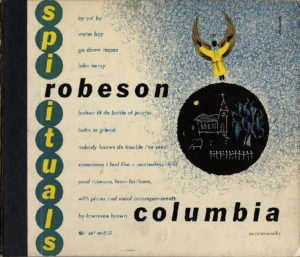

Paul Robeson – Spirituals Columbia Masterworks Set M-610 (1946)

Possibly Robeson’s best album. There are few singers with a voice as capable of commanding of attention as Paul Robeson’s. His deep, resonant bass-baritone is so iconic that the man’s portrait should probably appear in dictionaries next to the word “dignity”.

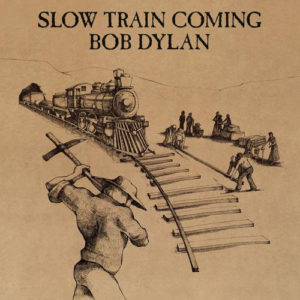

The recording of “John Henry” included here is one of Robeson’s very finest. The Legend of John Henry is an old neo-Luddite folk tale, based on a real historical person (or amalgam of many real persons) working to build a railroad line, probably as convict labor after the Civil War, about a poignantly suicidal triumph of labor over the technology that owners of capital wield to destroy the means of workers’ support and dignity. John Henry defeats a spike-driving machine in a one-on-one competition, only to die of exertion. Lawrence Brown‘s somber piano provides deftly understated accompaniment. Brown plays in response to what Robeson sings, in the black tradition of call-and-response. The way Robeson sings is amazing. He uses controlled vibrato, just as any trained opera or bel canto pop singer would. His enunciation is impeccable. Every word is booming yet unmistakable. But he sings the song with non-standard diction. This places him halfway between vernacular music (true folk “spirituals”) and the ordained and accepted music of society’s ruling classes (“hymns” in the religious context). Spirituals came after Robeson’s political radicalization, and it is easy to look back at it and see how his approach to performance injects the vernacular into dominant forms as a kind of bottom-up revolutionary act, as performed by a black man in Jim Crow America who sings so well and with such unmistakable facility for bel canto pop music that he cannot be dismissed as an untalented ruffian making a bunch of mere noise.

Michael Denning‘s book Noise Uprising chronicled the revolution from below made possible from 1925-30 by the advent of electrical recording technology — before the Great Depression collapsed the global market for such records. Paul Robeson represents a different sort of revolutionary stance, though not necessarily an entirely different one. Robeson took advantage of electrical microphone technology to capture his voice in ways never before possible (his record label recorded him with the very latest technology). He also balanced the expectations of the powerful with the interests of the downtrodden. And he did so very, very well. His use of vernacular elements was more limited though, focused on more precise, subtle mobilizations in his vocals. Take “Balm in Gilead,” which slurs the words “there is” to sound a bit like “dere is” in a line otherwise enunciated with stately exactitude. These effects let you know which side Robeson is really on. He can sing in accordance with all the rules the powerful insist upon, but he carefully deviates from them, to inform the audience that he is choosing to do so, for purposes that are manifestly not dictated by the powerful.

On “Nobody Knows de Trouble I’ve Seen” Robeson sings the last line “glo_ry, Hallelu__jah” with an abrupt shift in his intonation of the last syllable of the word “Hallelujah” to express a kind of release and hopeful promise that stands in contrast to the somber weariness of the rest of the song.

Lawrence Brown sings accompaniment too. On “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho” he adds responses to Robeson’s leads. Brown’s higher pitched voice, and quicker, less noticeable vibrato are counterpoints to Robeson’s booming voice. The tempo is much faster than most of the songs on the album too. It is followed by another duet song, “By an’ By.” Brown’s lines are phrased in a heavier vernacular, though one that comes across as slightly studied and academic — in other words, staged and inauthentic. This places Robeson is a kind of hero role, making his voice sound more commanding and impressive.

The albums wraps up with three tour de force solo vocals: “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” “John Henry” and “Water Boy.” The last two songs are part of Robeson’s standard repertory. He performed those songs in most concerts and recorded them multiple times. “Water Boy” uses melisma to the maximum. Robeson’s use of vibrato is also a thing to behold. He carefully controls the vibrato over long, sustained notes to match the rhythm of his vocal phrasing. Much like “John Henry,” “Water Boy” is a kind of hero tale, framed as (presumably) an adult boasting to a “water boy” of his strength and capabilities as a worker. It is at once a celebration of labor and a vehicle perfectly suited for a black man in the Jim Crow era to demonstrate prowess as a singer.

If all this makes Robeson seem too much of an activist, when all he was doing was singing, then it is worth considering what happened to him in the following decades. His passport was illegally denied and he was blacklisted. His son also alleges that the CIA surreptitiously conducted “mind depatterning” on him as part of Project MK-Ultra (probably with LSD). The powerful knew that Robeson and his music were indeed a threat to white supremacy and other forms of oppression. It is a bit difficult to walk away from hearing a Robeson recording like Spirituals without some degree of respect, if not awe.