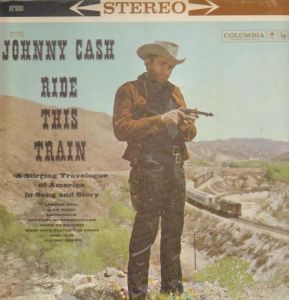

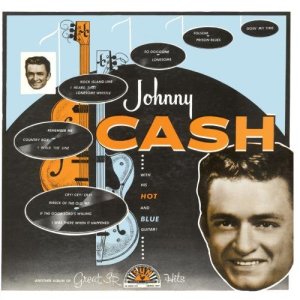

Johnny Cash – Johnny Cash With His Hot and Blue Guitar Sun LP-1220 (1957)

Johnny Cash was an artist who sort of arrived with all his major talents intact right from the beginning. His music evolved and changed over time, for sure. But his velvety bass-baritone voice and endearing brand of time-worn country wisdom are all in full effect on this, his first full-length LP. Being the early days of the LP format, this material wasn’t strictly recorded for the LP and many of these songs were previously released as singles. They were recorded between May 1955 and August of 1957. Cash plays with guitarist Luther Perkins and bassist Marshall Grant, the original Tennessee Two. It’s a very spare and minimalist sound, which lets Cash’s inimitable voice take the spotlight. Perkins was a guitarist of pretty limited means. He really couldn’t play much more than a simple boom-chicka-boom rhythm, without any complex solos to speak of. He does a lot of the typical country strumming, alternating between low notes and high notes in the style of Maybelle Carter. But it’s iconic. Perkins was the perfect guitarist to support Cash. His playing has a little bit of rock influence, but that just provides a little, subtly energetic, minimally urban counterpoint to Cash’s traditional country leanings. The other key aspect of the sound of this record is the reverb. Like much of the music recorded at the legendary Sun Studios in Memphis Tennessee, the reverb drenches the music in seductive, politely dangerous charisma.

The songs here are great. They include Cash’s first hit, “Cry! Cry! Cry!,” a Hank Williams tune, “(I Heard That) Lonesome Whistle,” and a song probably written by Charles Noell about a 1902 train wreck, “The Wreck of the Old ’97.” “I Walk the Line” was a song Cash liked to say was his best, and it’s hard to argue. Another of his most famous compositions, “Folsom Prison Blues,” was written after Cash saw the film Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison while in the U.S. Air Force stationed in Germany. He pretty liberally borrowed the melody and lyrical structure of Gordon Jenkins‘ “Crescent City Blues” (part of “The Second Dream – The Conductor” from Gordon Jenkins’ Seven Dreams (A Musical Fantasy)), and paid Jenkins in the 1970s for what he borrowed. He also adapted the famous line “I shot a man in Reno/just to watch him die” from Jimmie Rodgers‘ “Blue Yodel (T for Texas)“: “I’m gonna shoot poor Thelma/just to see her jump and fall.” (Rodgers’ song in turn was a pastiche drawn from numerous sources). But Cash’s song is superior to any of its reference points. “I Was There When It Happened” is a country gospel number. Cash wanted to perform gospel music from the beginning, but opportunities were limited to record it in the early days. It would remain a factor in his music for his entire career.

What made Cash so special is damn hard to put your finger on. He sang about a lot of the ordinary aspects of life: work, travel, liberty, death, religion. He did do romance and love songs, but a lot less than many other famous singers. When he did do them, they weren’t anything like the hyper-sexualized fare that came to dominate rock music. There was a connection to the “old weird America” that Greil Marcus described with respect to Harry Smith’s iconic Anthology of American Folk Music. Cash’s songwriting, as well as his song selection, tended to emphasize an “ordinary” individual’s reaction to extreme situations: being confined to prison, natural disasters, threats to making a living, and so on. He confronted these situations with varied amounts of humor, lament, determination, dignity and enthusiasm. Yeah, Cash could take these situations and make them fun and funny. But that’s just the way his music reflected how human being sometimes deal with stress and tragedy, and what they aspire to in the best of times.

Cash only stayed at Sun Records for about three years. Sun continued to release his recordings for years after he left, in part because Cash left for a bigger label before his Sun contract was finished, forcing him to do a few contract-fulfillment recording sessions after he announced his departure. Although this album sounds unmistakably of its time, it doesn’t really sound “dated” at all, in the sense of losing its appeal to modern audiences. This is one of the essential Cash albums. There is not a bad track on the whole thing.