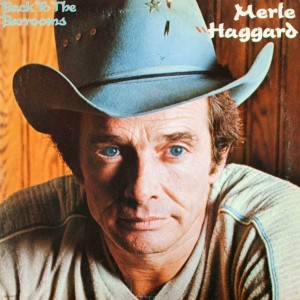

Merle Haggard – Back to the Barrooms MCA MCA-5139 (1980)

Merle Haggard had something of a career renaissance in the early 1980s (plus another in the early 2000s). There was a popular duet album with Willie Nelson, Pancho & Lefty (1982), that resonated with the “urban cowboy” set. But it started with Back to the Barrooms. He doesn’t touch the political subject matter that made him notorious a decade before (The Fightin’ Side of Me, Okie From Muskogee). Instead, there are a lot of hard drinking songs, just like in the earliest part of his career (Swinging Doors and the Bottle Let Me Down). But his sound is much different than the early days. There are strings, a saxophone, and a generally lighter touch in both his vocals and the musical accompaniment. This recalls old-fashioned honky tonk — with plenty of single-string solos and Travis-picking on guitar, bouncing country walks on the bass, and echoes of barrel-house strides on the piano — but it also ponders what to do with electronic processing in the studio while remaining authentic country music. It isn’t quite “urban cowboy” yet, because the balance between urbane synthesizer-driven easy listening pop and gruff rural twang leans too much to the latter. But this isn’t dated (like many Chips Moman productions from this era: Flyin’ Shoes, Always on My Mind, Rainbow). It is perfectly comfortable in its sound.

The songs are all about conflict. It is personal conflict. What makes the album so compelling is that it is a battle the singer has with himself. He has temptations, failings, and he knows it. He has his petty excuses, without stooping to make them out to be anything more than that. Depression and substance abuse loom large. Nevertheless, there are really no scapegoats.

The songs oscillate between ways of recounting heartbreak and such, finding each one incomplete but also without hypocritically denouncing the last with the next perspective. The music orbits something that just can’t be conveyed directly. One the one hand, there is some sympathy for the classic working class belief that family is important, more so than career, wealth or acclaim. And (American) families start with romantic relationships. On the other hand, there is the emptiness of career and fame (much like Loretta Lynn‘s early career song “Success,” with the line: “success has made a failure of our home”). Songs like “Leonard” hit on this — the song is about Tommy Collins, but much of it could be about Hag’s own downward spirals and rehabilitations too. The emptiness, though, is a reflection of how ordinary fame seems, that when achieved it has none of the revelatory, transformative qualities presumed beforehand. What we have is a framing of personal conflict that really perfectly suits Haggard at this point in his life. Yes, he had success, but what of it? Is it true that you can “never go home”? There are number of books that deal with people from working class backgrounds going into academia (This Fine Place So Far from Home: Voices of Academics from the Working Class, Strangers in Paradise: Academics from the Working Class, etc.). Some of the stories in them are remarkably like what emerges from Haggard’s Back to the Barrooms. He is conflicted about his roots, and the milieu of musical celebrity status. Some of the best bits — like “I Don’t Want to Sober Up Tonight” or “Can’t Break the Habit” — are when he just says, “I don’t want to act like things are alright / And I don’t want to change just to make you think I’m happy / And that’s my right, I don’t want to sober up tonight.” This is the tension not just about resisting alcoholism, literally, but also about not wanting to totally give up on your humble roots when you “upclass” to a different social strata. Haggard knows what success is about, and he doesn’t see a place for himself in the “perfect” world of a 1980s country music star. But the modern touches and crooning suggest that he isn’t ready or willing to just go back to his old way of singing, before his biggest successes, to his pre-fame roots. He looks back to the past, which isn’t simply duplicated, but re-enacted with an awareness of more than just the past. He can’t unlearn everything that came in between.

Haggard always had a softer side, and his voice was remarkably versatile. He may have been a pioneer of the Bakersfield Sound, blending rock influences into country, but he could sing tender ballads to match any country crooner. The opener “Misery and Gin” is one of the best examples of what this whole album offers. Haggard’s voice opens the song with smooth crooning, going to a higher pitch than some country singers could, with a little bit of vibrato. But he opens the vibrato up a bit, and he swoops down to a kind of sing-speak rumble. He starts some lines perfectly sweetly (“..to myself” and “but any foo___ol can tell”), then he mixes in clipped, accented pronunciations (“ta-night” not “tonight,” “sittin’ with all my friends” not “sitting with all of my friends,” a hard emphasis on the “HON” and “TON” in the line about “this honky tonk heaven”) and quickly runs through some of the lyrics (“…really makes you…”) like a sly afterthought. It’s like he goes from being (almost) a sweet pop crooner in the style of Bing Crosby to one of his musical heroes, the “singing brakeman” Jimmie Rodgers. If Haggard hadn’t gone beyond his “roots” he would have had no credibility to convey the gap between them and the kind of distant sophistication that goes with poppier and slightly more urban music that was commercially successful at the time. Paradoxically, this is what makes the music authentically personal, by conveying the divided convictions of a guy shifting between two different positions that are too different to be synthesized and who inhabits the no-man’s land between them.

The title track is sequenced second. Its placement after “Misery and Gin” is telling of a pull to return to some sort of earlier state, just as the third track “Make-Up and Faded Blue Jeans,” trading riffs of slick, jazzy electric guitar and light, ’80s soft rock saxophone, returns back to an idea of an urbanized lifestyle that is a requirement to succeed as a professional musician — even as the lyrics speak about relapse and faltering at maintaining a mere image of urban sophistication. “Back to the Barrooms” has a much more solid “country” foundation than the opener. Yet if placed side-by-side with an early Haggard classic (“Please Mr. D.J.,” “Mama Tried,” “Swinging Doors”), the formal similarities in song structure give way to pronounced differences in Hag’s phrasing — he’s holding notes longer, leaving less space between verses, and softening the delivery to avoid the harder rhythmic attack of the past. And the electric guitar and compressed tone of the drums’ sound embrace musical technology (something profoundly urban almost as a matter of course) in a way totally alien to his 1960s and early 70s work. His earlier recordings tended to use prominent electric guitars to emphasize a sturdy toughness on more rocking, up-tempo numbers (“Workin’ Man Blues,” “I’m Bringin’ Home Good News,” “The Fightin’ Side of Me”), and relied more heavily on acoustic instrumentation to support tender, sensitive ballads (“I Started Loving You Again,” “I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am,” “Silver Wings,” and even “If We Make It Through December”). Here, he’s using (then) state-of-the-art technologies to expand upon the ballads and crooning. This is a surprising — and surprisingly effective — reversal of expectations.

There are a lot of reasons to dismiss an album like this. But there are more reasons to dig in and appreciate it as an inspired confluence of supple commercial ambition, gruff obstinance and autobiographical connection. Much of the album takes on multiple layers of meaning. It inscribes the hesitations and burdens of stardom with longing for the past and resigned acceptance of how that past was jettisoned along the way. Haggard always was at his best when his music was straight from the gut and personal. Yet he rarely sounded so consistently wise and vulnerable at the same time as he does here. Back to the Barrooms is a portrait of Haggard as neither a graceful success nor a simple nobody, but rather as somebody in an elusive middle ground scrambling to finding meaning in that place of limbo.