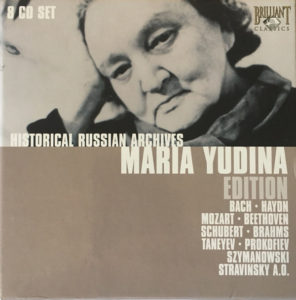

Мария Юдина [Maria Yudina] – Historical Russian Archives: Maria Yudina Edition Brilliant Classics 8909 (2009)

Maria Yudina was arguably the most highly regarded Soviet pianist. There are tons of great anecdotes about her. One of the most famous is that, as a devoted christian in the militantly atheistic Soviet Union, she wrote to Josef Stalin to say she would pray for him! Her religious beliefs did hinder her musical career, though it was actually normal for people to criticize Stalin and her music was not a political threat to him; hence, she was spared from the great purges. David King‘s book Red Star Over Russia details another anecdote in which he was attempting to return to the West from a research trip to the Soviet Union and was stopped at the border where photographic film he carried was discovered. Exporting exposed film was, at that time, something subject to extreme scrutiny. He was referred to a more senior interrogator, and he told her was researching Yudina. The official immediately said that Yudina was her favorite musician, and ordered the border guards to let King pass, film and all, because he was researching Yudina. Yet another notable episode, also described in King’s book, is that during the Siege of Leningrad, “the 900 Days” during which the Axis military, as part of Operation Barbarossa (the largest military offensive in human history), blockaded the city. Isolated by the siege, and supplied only by a dangerous ice road, underwater pipeline, and occasional, dangerous flights, civilian deaths were astonishing. Tanya Savicheva’s diary, which recorded how each of her family members starved and froze to death one by one around her, is kind of the “Diary of Anne Frank” of the siege. Yudina was flown into Leningrad during the siege, in order to perform music so as to boost morale. This speaks to what she meant to listeners; it was important that she be flown in (taking up space on the plane that could have been used for more supplies). She of course suffered the same deprivations as the local inhabitants while in the besieged city.

Yudina’s playing was highly emotive and conveyed a sense of strength. She never played to exhibit finesse for its own sake. What is most remarkable was her versatility and her unique interpretations. One way to describe her is as a gregarious and strong-willed counterpart to Glenn Gould. The anecdotes recounted above each convey something about Yudina that shines right through her recordings. She performed music by a wide variety of composers, including some notably modern compositions. She was even in contact with Darmstadt school composers like Boulez and Stockhausen. Recordings of her music are, unfortunately, somewhat hard to find in the West even after the overthrow of the USSR. But this collection, for a time (it is out of print now), chipped away at that problem.

This box set encompasses many composers. Listeners will likely favor some composers over others. I happen to like disc 8 with Hindemith, Honegger, Shaporin, Martinů and Jolivet the best (all pieces, unsurprisingly, recorded during the Khrushchev Thaw), as well as the first disc of Bach. There is also an intriguing disc of Prokofiev and Debussy pieces, in which the Prokofiev is played in the atmospheric, hazy style of Debussy and the Debussy is played with sharp, harsh modernist flourishes. And all this is to fail to mention the wonderful Taneyev disc. My least favorite here is probably the second disc of Haydn, Mozart and Mussorgsky. She performs with string players on numerous tracks, and they are uniformly strong, often playing with a scrappy, weary tone.

It is difficult to summarize this collection, because it is so varied. But that is really its strength. It also is music that reveals itself more and more with repeated listening. I previously had obtained a collection of Toscanini recordings (once it was budget priced), because a favorite high school teacher of mine used to play us Toscanini videos as part of his “culture for clods” series, and also because a stuffy old Euro-classical encyclopedia I once bought at a used book sale listed Toscanini as the “reference recording” for just about every major composition. While much of it is good, it lacks the range and memorable performances of this Yudina collection. Though that is partly a personal preference. Yudina was much more of a modernist than Toscanini. If this collection has a significant fault it is that it lacks detailed information about the the format and date of prior release for the included recordings — something that is difficult to ascertain without reading Russian — although recording dates and personnel is listed for everything.