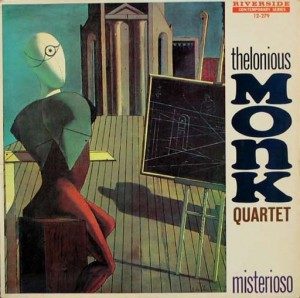

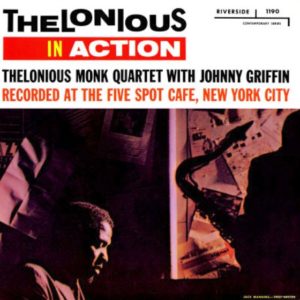

Thelonious Monk Quartet – Misterioso Riverside RLP 12-279 (1958) and Thelonious In Action Riverside RLP-12-262 (1958)

Thelonious Monk lost his cabaret card in 1951, which prevented him from performing live in New York for a number of years in the 1950s. But he regained it and undertook a long stand at the Five Spot Café in 1957. He returned to the Five Spot in 1958 with another band, documented on two albums: Misterioso and Thelonious in Action. The Five Spot was a small club in the Bowery. Monk’s appearance there was crucial in establishing the club as a congregation point for bohemian types like the Beats and assorted hangers-on — a good description of the club’s clientele and their motivations is found in the book The Battle of the Five Spot. It was around this time that Monk enjoyed some of the widest critical acclaim of his career, and, relatively speaking, his music was commercially successful too.

The 1958 Five Spot band played hard bop, of a kind that sort of epitomized its hip bohemian qualities. As usual, Monk was reprising a lot of his own songs he had played and recorded before, along with some standards. But “Light Blue” and “Coming on the Hudson” were original compositions that appeared on record for the first time on Thelonious in Action as was “Blues Five Spot” on Misterioso.

Johnny Griffin was the group’s tenor saxophonist. While both albums are well-respected, Griffin’s performances tend to draw more split opinions. That may be because his style of playing, on the one hand, deploys a kind of showy exposition of lighting fast fingering, and, on the other hand, quotes trivial pop melodies and floats away from the songs in a modernistic way the points beyond hard bop conventions. His more loose and freewheeling solos appear on Misterioso. The drums and bass are fine, but are mostly anchored in a very conventional hard bop style, especially the walking bass. Monk’s own playing is more gregarious than usual here. Compared to the free jazz explosion just starting to appear — Cecil Taylor‘s group was booked at the very same Five Spot Café in late 1956 and Ornette Coleman‘s quartet would kick start the revolution from the club the following year — this stuff is comparatively tame, but it still points in that direction. In a way, it is possible to look at these albums as a kind of breaking point that map out the limits of where conservative and reactionary jazz listeners and critics started to bail out, as the overall commercial prospects for jazz music began to erode in the face of the growing popularity or rock ‘n roll (and folk).

These are some of the most beloved albums in Monk’s entire discography. I do think some go overboard with praise for these — nothing here quite matches Monk’s best Blue Note sides, for instance. But there is also plenty of room for a lot of great Monk albums, and these two certain belong somewhere among the best of them — “Misterioso” and “Blues Five Spot” are perhaps the best individual songs here.