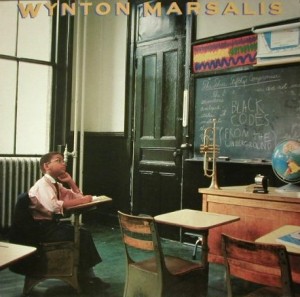

David Ruffin – My Whole World Ended Motown MS685 (1969)

Take a hundred albums at random, no ten thousand, and chances are you won’t end up with even one with the depth and sweetness of My Whole World Ended. It’s hard to go wrong with Motown’s golden age soul, which practically offers a guarantee of one or two classics somewhere on a full-length LP. But it was rare before the 1970s for Motown to produce an album that felt like a classic as a whole. To that short list add David Ruffin’s solo debut.

Ruffin was a singer gifted with a one-of-a-kind voice, but he was also someone who paid his dues and put in the work to learn what it takes to be a soul singer. Through his teens, he was touring in gospel shows and had first-hand experience with just about all the biggest acts on the gospel highway, Mahalia Jackson, The Blind Boys of Alabama, The Swan Silvertones, you name it. He was even in The Soul Stirrers briefly. A gospel background was the secret weapon of many great soul singers, and Ruffin had that pedigree too.

Of course, the reason most people know Ruffin is as one of the lead singers of The Temptations. He might be the only lead singer they recognize, from his lead on one of the most instantly recognizable pop songs ever recorded, “My Girl.” Fans might also know his lead on other greats like “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” too. A few other things might come to mind if you know anything beyond Ruffin’s music. He developed a reputation as a prima donna. He wanted The Temptations to rename themselves “David Ruffin & The Temptations.” Through the years he developed a massive cocaine habit as well.

After finally exiting The Temptations, Motown gave Ruffin every opportunity for his solo debut. He got the best songs, the best producers, and of course probably the best studio band around, The Funk Brothers. This album came out of the Hitsville, U.S.A. assembly line. It bears all the hallmarks of the classic Motown sound, with throbbing bass from James Jamerson punctuated with horns, strings, woodwinds, and backing vocals. With the handful of producers on board this never settles into any sort of rut, but these musicians worked together so much that there is still a cohesion. The best part is that almost nothing repeats. These songs grow and evolve. They don’t just extrapolate a simple riff. The embellishments vary too. One moment it’s horns, the next strings, the next some vocals, then a harpsichord, elsewhere a flute, and a few time some hints of bells are draped over the top. A light touch keeps the arrangements from crowding out Ruffin’s vocals, and, as one of the supreme achievements, the orchestration fits the core electric soul instrumentation like a glove. Take the backing vocals too. They don’t resemble what The Temptations did. These have no doo-wop roots. They come across casually. It’s like some friends wandered along and just couldn’t help but sing along. But they keep their voices down, to be polite and supportive.

These songs all have a dark side. Just look through the words in the song titles: worlds are ending, everything is lost, there’s a double-cross, there’s darkness, dreams have been stolen, and this guy’s baby is gone. When you then read a title like “Message from Maria,” could it possibly be a hopeful message? Not in the bleak universe Ruffin crafted.

All this discussion hasn’t even touched on the magnificent vocal performances yet. David Ruffin has a voice that almost any soul singer would die for. There is a grit and coarseness in it that makes every note seem like a bitter and tragic struggle. And that’s every note. When bolstered by the sweet, sumptuous music, Ruffin’s voice conveys a great tragic sense of loss. But not an everyday loss. This is world-crushing loss. It cuts, like a deep wound that might never heal.

“My Whole World Ended (The Moment You Left Me)” opens the album. The first things heard are woodwinds and strings with heavy maracas. Only after a few moments is a syncopated beat introduced. When Ruffin enters, he’s humming. By the time he’s singing, “Last week my life had meaning…,” there is no question that the star of this album has arrived. Some of the lyrics rhyme, but only a few. They are about holding on to find a new world, now that the old is gone. But it almost doesn’t matter what the words are. Ruffin’s voice has all the ache and sadness needed. His voice alone conveys the heartbreak. This is a song perfectly suited to his style of singing. He’s always shifting, singing with a bit of a smooth crooner’s style but marked with gravelly texture, and broken up with melismata and added phrases (“aww, tell me baby,” “oh yes it did, baby, baby”). He’s cataloging ways to cope with loss. This is a song that can make an album. It’s a song that, in the right setting, could just play again and again on repeat and no amount of repetition would ever be enough. Yeah, it’s that good.

“Everlasting Love” has been sung by many others. When Ruffin does it here he seems adrift. He’s mining all the drama in the song. The confines of the rhythm aren’t enough to hold him. He even screams. It seems like a love song, but it’s also a plea, built from regret, longing and loneliness.

So much bleakness and uncertainty…it’s only a few hard-fought personal connections that seem tangible on My Whole World Ended and in that this feels like a grounded sort of music. There isn’t the mysticism of Van Morrison‘s Astral Weeks, but this one feels like a more pubic version of the same searching, longing and obsession that fuelled Morrison’s classic. Ruffin is posed on the album cover almost like Rodin’s “The Thinker,” and (apart from the corny globe in the background) he’s making a thinking person’s album.

There are a lot more great songs here, “I’ve Lost Everything I’ve Ever Loved,” “My Love Is Growing Stronger,” and “The Double Cross.” These tunes run a gamut from slow ballads (“Somebody Stole My Dream,” “Message from Maria”) to mid-tempo, funky rockers (“Pieces of a Man,” “Flower Child”) and even a roiling, off-kilter rocker (“World of Darkness”). My Whole World Ended is just one of those albums that is worth it. It was a hit in its day but for some reason tends to be left off the list of essential soul classics. Rescue it, if only for yourself.