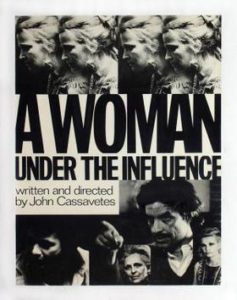

A Woman Under the Influence (1974)

Faces International Films

Director: John Cassavetes

Main Cast: Peter Falk, Gena Rowlands

John Cassavetes’ wife Gena Rowlands asked him to write a play with an interesting female character for her to perform. That play ended up being unsuitable for live theatrical performance and was instead re-purposed as the film A Woman Under the Influence. Rowlands plays Mabel Longhetti, a stay-at-home mother of three children. Her mental disposition is one that is inconvenient to modern society (there being no objective definition of a “normal” mental state). Her husband Nick (Falk) is a working class construction worker. Nick is a rather angry and occasionally violent doofus who genuinely cares for Mabel. The film examines the reactions of ordinary people to Mabel’s unconventional behavior, and Nick’s attempts to cope with it — and to try to control it (and her). Mabel’s eccentricities eventually lead to her being committed to a mental hospital for six months — of note, Nick’s violent outbursts at home and work do not lead to him being committed or imprisoned. Nick proves inept but well-meaning as a sole parent during Mabel’s absence. The film concludes with an extended portrait of Mabel’s return home from the hospital. Nick planned a welcome home party, though the presence of a crowd is questioned by his mother (Katherine Cassavetes) as being too stressful for Mabel. As the guests eventually are thrown out by Nick’s mother and then Nick, Mabel clumsily attempts suicide, and her children become distraught. In a fitting conclusion echoing the ancient myth of Sisyphus, Nick carries his children upstairs to their bedroom only to have them run back downstairs to their mother and the process repeats. Such a “punishment” is fitting for Nick, as a self-aggrandizing jerk whose children seem more genuinely connected to their mother as a person with her own free will than he does.

A Woman Under the Influence is one of the “mature” Cassavetes films, in which his style that blends intense scripted and improvised acting expands upon what he had done in earlier films like Faces and Husbands, notably improving upon the overall pacing, while also deploying a much less conventional narrative structure than Minnie and Moskowitz. Rowlands and Falk give tremendous performances. Cassavetes’ narrative examines the characters’ personal situations from a sympathetic perspective, with his iconoclastic film techniques offering a much deeper palette of complex emotions than is typical in movies. What sets A Woman Under the Influence apart from Faces is that, here, a couple is struggling to keep their family together, whereas Faces saw characters striving to break free of social constraints (while ironically and cynically doing so to seek social validation). The two main characters are each unusual for feature length films, in that middle aged, working class protagonists are usually portrayed only at the margins of Hollywood cinema and the industrial nature of film production prices out most would-be independent ventures that might otherwise show interest.

These characters are all flawed, but worthy of human dignity nonetheless. Nick’s struggle to control the people and situations around him — and his frequent inability to do so — is his most pronounced character flaw. Mabel is less a “flawed” character as much as one with a combination of inability and unwillingness to conform to social expectations. Cassavetes’ movies often featured a free-spirit “hippie” character (often played by Seymour Cassel). The Mabel character is sort of a twist on that theme. This prompts frequently draconian reactions. Mabel’s commitment might be compared to the real-life story of the feminist scholar Kate Millett. This is the “hysterical woman” motif:

“Remember what hysteria is? To simplify it, from a psychoanalytic standpoint, society confers on you a certain identity. You are a teacher, professor, woman, mother, feminist, whatever. The basic hysterical gesture is to raise a question and doubt your identity. ‘You’re saying I’m this, but why am I this? What makes me this?’ Feminism begins with this hysterical question. Male patriarchal ideology constrains women to a certain position and identity, and you begin to ask, ‘But am I really that?’ Or to use the old Juliet question from Romeo and Juliet, ‘Am I that name?’ Like, ‘Why am I that?’ So hysteria is this basic doubting of your identity.”

The sympathy that Cassavetes shows his flawed characters is unique. Unlike, say, Pier Paolo Passolini‘s underclass protagonists, like the titular character in Accatone, Cassavetes’s films often deal with characters situated away from class conflicts. The Longhetti family is working class, but we see them with a comfortable home and steadily employed without obvious want. This allows for a unique focus on the characters’ inner psychology, in which viewers can witness the characters questioning their own actions and pursuing changes in their lives while at the same time struggling to make the right changes and repeatedly failing to actually change their desires as reflected in their actions. While certainly many other filmmakers relied on psychology to inform their work, Cassavetes was unique in the raw, harsh and almost bleak realism with which he depicted these things. His films are largely free of simplistic symbolism. Surprisingly, it is an approach that shared some similarities with some films of the Socialist Realism genre, such as Béla Tarr‘s early short Hotel Magnezit, albeit with the freedom to explore subjects other than a critique of bureaucracy.

In the end, A Woman Under the Influence remains a “difficult” film filled with enough heart to remain engaging from beginning to end. This is another landmark of American cinema from one of its greatest writer/directors.

![Poesía sin fin [Endless Poetry]](http://rocksalted.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Endless_Poetry.jpg)