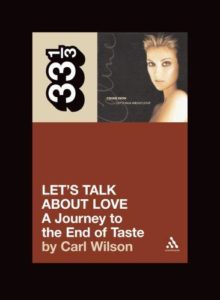

Carl Wilson – Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste (33 1/3 #52) (Continuum 2007)

Carl Wilson tackles Céline Dion‘s album Let’s Talk About Love. His approach is intriguing, based mostly upon the theories of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (particularly as set forth in his Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste). In essence, Wilson asks whether his distaste for her music is really a way to distinguish himself from her fan base. While the basic premise of the book is worth reading about, Wilson stumbles a bit when going about applying the theory to the work of Céline Dion. For one, Bourdieu was insistent that the point of his analytic framework was to expose systems of domination in order to permit them to be challenged. Wilson, though, eschews that sort of purpose. He notes that aspect of Bourdieu’s theory but glosses over it in his own analysis. He instead ponders endlessly how her fame doesn’t make sense. But it does! The essence is that she supports modes of domination, providing a convenient coping mechanism for the victims of domination without challenging the oppression by the powerful. She is therefore supported and promoted by those who benefit from that domination (key to her having a huge Las Vegas show). Wilson skirts this issue. Take this passage concerning her penchant for sentimentality:

“Her songs are often about the struggle of sustaining an emotional reality, about fidelity, faith, bonding and survival — continuity, that is, in the destabilizing flux of late capitalism. While business and rebel-schmaltz stars alike tout self-realization, social negation and the delegitimation of traditional values, Céline’s music (like Nashville country) tends to prioritize ‘recognition and community,’ connection and solidarity. Granted, she also promotes overwork, ambition and luxury, which is to say she’s still a pop star. But in that matrix, sentimentality might be her greatest virtue.” (p. 127).

Wilson is right that the palliative aspect of her sentimentality can be seen as a redeeming quality, but in positively noting that perspective he deflects attention from who benefits from it. He recounts an amusing anecdote about how Jamaican gangsters often played her music loudly. Isn’t the core of gangsterism the direct, physical expression of domination, just as Céline’s music is a facilitator of it through the more subtle economic and political mechanisms of late capitalism? Gangsters liking it makes perfect sense when ideological alignment is considered.

There are many perspectives on Céline’s music that Wilson never quite considers. He comes close for some. He talks about how Céline appeals mostly to people who make use of her music, for weddings, events, and as the soundscape of life, not people (like professional critic Wilson) who scrutinize and analyze it. Joe Boyd in his memoir White Bicycles, wrote about how in the 1960s folk music scene there was a divide between those like archivist Alan Lomax who pursued “gregarious” music meant for social events — sing-alongs and such — and record collectors more interested in virtuoso performers. This is a very similar divide between Céline’s fans and Wilson and his cohorts. But he does not really go there in the book. Also, could it be that Céline’s music appeals to extroverts, while most music nerds are introverts? This is not to say that these other lenses are the correct ones, but rather that the way Wilson struggles to find an explanation for Céline’s appeal means that he never quite has the crucial insight that explains the divide between her fans and her many detractors. Put more simply, this is why Wilson’s approach is unscientific and superficial. He acknowledges that he lacks the funds to perform a large survey like Bourdieu (for that, look to the likes of Gerry Veenstra). He would be better off looking to the style of Thorstein Veblen, but he disses Veblen and misquotes him (flattering himself by trying to coin the phrase “conspicuous production” in a way that is already subsumed by Veblen’s original theory of “conspicuous consumption”).

There are many passages of great insight in the book. They unfortunately don’t hang together into a whole, and are offset by unfortunately blunders. For instance, Wilson contrasts Céline with the Carpenters. And yet, the Carpenters are actually credited by many with creating the genre of pop power ballads (“Goodbye to Love”) that are the core of Céline’s repertoire.

The extensive personal anecdotes that Wilson injects throughout the book are a distraction. While those sorts of things can orient a reader to the ideology and perspective of the writer, Wilson is not as candid as he claims to be (for one, he points out that he writes for leftist publications, but his endless claims about misunderstanding Céline’s music is purely centrist liberalism). The book would have been better without those digressions. It could have stood to go much further into the application of Bourdieu’s theories as well. What’s more, his eventual “review” of Let’s Talk About Love is limp and uninteresting.

In spite of its limitations, one hopes that Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste still encourages other writers to take up a similar approach to criticism. There are few more intriguing ways to look at the nature of criticism. (Actually, David Lee‘s The Battle of the Five Spot: Ornette Coleman and the New York Jazz Field is a much more substantial book applying Bourdieu to jazz music and practice, or look to various French writers who have done this in the past).