Link to an interview with Michael Hudson by Sharmini Peries:

Month: April 2016

Scott Walker + Sunn O))) – Soused

Scott Walker + Sunn O))) – Soused 4AD CAD3428CD (2014)

Scott Walker continues to challenge himself and audiences. With Soused, he has teamed with drone metal outfit Sunn O))). Comparisons have been drawn to Lou Reed‘s collaboration with Metallica on Lulu (2011), but comparisons could equally be drawn to Tony Conrad working with Faust on Outside the Dream Syndicate (1972). The album opens strongly with the two best tracks, “Brando” and “Herod 2014.” “Brando,” which might have been inspired by the strange Arthur Penn western The Missouri Breaks (1976) starring Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson, sounds the most like Walker’s most recent albums. There is a recurring riff a bit like Guns N’ Roses‘ “Sweet Child O’ Mine,” deflated and blunted. The second track, “Herod 2014,” is the story of a mother hiding her children…from something not really named. The song title is a reference to the biblical king of Judea. There is a small bell that is repeatedly rung throughout the song, somewhat loudly at first but then pushed back into the background so that it is barely perceptible. In an interview, Walker said, “The bell, in a sense, is representing her.” The rest of the tracks, all written by Walker, come closer to the usual sound of Sunn O))). They aren’t quite up to the first two tracks, but they don’t disappoint either. This is a grim, confrontational album that tries to provoke and prod listeners. But it also draws on plenty of dark, gallows humor. It may not be the finest from either Walker or Sunn O))), but it is a worthy collaboration that finds a lot of common ground.

The Holy Mountain

The Holy Mountain (1973)

ABKCO Films

Director: Alejandro Jodorowsky

Main Cast: Alejandro Jodorowsky, Horacio Salinas

Alajandro Jodorowsky is really one the the most unique film directors of his time. The Holy Mountain opens much like The One Thousand and One Nights (especially Raoul Wash‘s The Thief of Bagdad), with a thief (Horacio Salinas) cavorting about a town. The town is a bit heavy on religious and military pomp (recalling both Fellini and Costa-Gavras‘ political thriller Z). There is much other symbolism, including characters modeled on Tarot cards. But then the thief hops aboard a hook being pulled up a minaret-like tower and enters the mysterious structure. A cloaked alchemist figure (Alejandro Jodorowsky) disarms the knife-wielding thief and then makes him his apprentice, telling him, “You are excrement; you can turn yourself into gold.” This, of course, in the premise of modern psychoanalysis.

The alchemist, acting as a “master” (Jodorowsky describes the character as “a sort of hybrid of Gurdjieff and the magician Merlin“), then introduces a montage of scenes describing his other disciples. These are powerful, wealthy figures, and yet, also the most outrageously surreal representations of society’s worst traits: domination, deception, decadence, exploitation. He summons them and they ceremonially burn their money and effigies. They set out on a quest to find the mythic Holy Mountain upon which hermits who know the secret of immortality have supposedly lived for thousands of years. They plan to capture the hermits and appropriate the secret.

The rest of the film is a surreal vision of an adventure movie, supposedly taking inspiration from René Daumal‘s novel Mount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing. A girl (Ana de Sade) with a monkey follows the master and his disciples. On the journey, the group is confronted with a series of tests to provoke subjective destitution, to surrender worldly desires. The master convinces disciples to kill him, literally and symbolically (though with a laugh, he is killed only symbolically in one scene despite literal intentions). The thief winds up with the girl with the monkey. Although Jodorowsky wanted the film to end in a paradise scene filmed in a Mexican restaurant with a woman (actually) giving birth on camera, the pregnant woman backed out at the last minute, scuttling those plans. Instead, the film ends in an equally remarkable way. The master orders the camera to zoom back, revealing the film equipment surrounding the actors — what is known in cinema as “breaking the fourth wall.”

Much like in Jodorowsky’s immediately prior film, the western El Topo, there is much emphasis on traversing the fantasies of religion (especially) and cultural desires. Jodorowsky very much makes his films according to Antonin Artaud‘s vision of a “theater of cruelty,” producing shocking, bizarre scenes to derange and assault the senses of viewers in the hopes of making them traverse their own psychological fantasies. Viewers are meant to be surprised by what they see, to encourage them to cut the Gordian knot of their own ingrained habits of thought imposed by culture (and especially by family). There is little doubt most viewers have never scene a movie quite like this! Yet for as much as he breaks down mythic cultural institutions and the illusions that symbolically bind individuals, he refashions mystic processes in an atheistic way. Here, he is concerned with a kind of frontier justice that fights symbolic problems with symbolic weapons, though later in life he changed his methods somewhat into what he calls “psychomagic”, a kind of “shamanic psychotherapy” — which perhaps can be described as using poetic rituals to self-administer metaphorical fulfillment of desires, to free the people burdened by those desires to engage reality on their own terms.

If there is any other artist worth comparing to Jodorowsky, aside from Artaud and perhaps Yoko Ono and Carlos Castaneda, it might be the jazz bandleader Sun Ra. In a documentary, an associate said that Jodorowsky liked to work in areas beyond his knowledge Sun Ra made an album called Strange Strings in which he instructed the performers this way: “We’re going to play what you don’t know and what you don’t know is huge.” While Sun Ra dealt in Afro-futurism, and especially Egyptian and outer-space mythology, Jodorowsky has a different set of things he draws from, like the Tarot. They both nonetheless share a very communal, mutually-supportive practice that draws on the strangeness of mythology and exoticism to promote self-empowerment and liberation. Contemporary philosophers like Alain Badiou like to talk about the need for positive statements about the world. Isn’t Jodorowsky exactly that?

Jodorowsky had difficulty funding many of his later film ideas, with his ambitious attempt to film a version of the sci-fi novel Dune falling apart before shooting began — recounted in the documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013). It took him almost a decade before he actually completed his next feature, Tusk (1980), and it was not until the horror film Santa Sangre (1989) that he really made something with close to full artistic control. He turned to writing comics and books instead of films when funding was not available. This seems partly a matter of the idealism that peaked in the late 1960s fading away. Jodorowsky’s work certainly sits in opposition to everything that the celebrity-driven, corporate, commodified mass culture of the following few decades.

While a dispute with the film’s distributor kept The Holy Mountain from widespread view for decades, it has become available again. It is quite a film, and its “comeback” has brought well-deserved attention to an artistic method that presents a substantially different approach than the mainstream. Love it or hate it, this won’t be a film easily forgotten.

Astra Taylor – The People’s Platform

Astra Taylor – The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (Metropolitan Books 2014)

“There is a war between the ones who say there is a war /

And the ones who say there isn’t”

Leonard Cohen, “There Is a War” from New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974)

Filmmaker and sociologist Astra Taylor has written an excellent and much-needed book about Internet technology, culture and economics, critiquing the so-called “Web 2.0” phenomenon. In the beginning of the book, Taylor sets up the supposedly false dichotomy of the debate about the Internet: tech-boosterism that sees everything about the Internet as great vs. Luddite anti-technology naysayers. However the rest of the book reveals that dichotomy to be kind of a slight of hand distraction. Taylor spends most of the book talking about how mainstream discussion of the Internet and its political and economic implications tends to be framed as a debate between the political center and the political right, with positions of the political left excluded. Taylor tries to inject a leftist position. So she critiques the likes of Lawrence Lessig for advancing what amounts to a Standard Liberal Position (i.e., the political center): finding the “right” amount of inequality. Taylor, on the other hand, advances the (largely blacklisted) Standard Left Position, which seeks an egalitarian society. She sees too much in common between the liberals, the fascists, the royalists, and the libertarian right, and therefore offers a politically different perspective, one that many people probably would agree with, except that they never hear it in the mass media.

She particularly objects to the neo-feudal aspects of “Web 2.0” that are premised on a neoliberal, techno-libertarian obsession with creating tycoons and massive inequality, without a democratically-controlled government to act as a check on private power, and tries to reveal the mechanisms those boosters try to conceal. This is the essence of social science. She fits into a long line of writers from Thorstein Veblen to Peter Drahos to Nicole Aschoff. Perhaps most on point in a general sense is Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello‘s influential The New Spirit of Capitalism, where they make the argument that corporate capitalism is co-opting the empowering rhetoric of the past (the New Left 1960s especially). Aschoff explicitly cites Boltanski on this point in The New Prophets of Captial. Taylor just adopts that same argument (perhaps reinventing the wheel a bit). But Drahos’ Information Feudalism is quite apropos too.

A rather similar observation about growing neo-feudalism has been made by the economist Michael Hudson, who has noted how the “free trade” of classical economics was meant to promote an economy freed from feudal aristocracy, rentiers, and any other predatory interests who sought to siphon off wealth through special legal/social privileges, whereas the neoclassical economics of the neoliberal era seeks to set up an economy free for predatory interests to set up wealth-extracting privileges akin to setting up private tollbooths on otherwise public thoroughfares.

Taylor’s book sets out a kind of narrative that maps rather well onto Hudson’s theory. For Taylor, the problem is that (a) Internet technologies are praised for the socially beneficial possibilities they suggest, with those possibilities backed by lots (!) of paid advertising. Despite considerable media attention, (b) little attention is paid to whether there is empirical validation for the theoretical possibilities that Internet technologies suggest. It is assumed that internet technologies produce positive results without many people bothering to check. Most importantly, (c) only those internet technologies that bolster concentration of wealth and capital are supported — those who do check up on empirical circumstances and report on the disconnect between theory and reality are marginalized and ignored. This last point is crucial. Usually the internet technologies that succeed are not the ones that actually provide the benefits they suggest, but rather ones that meet the dubious criteria of venture capitalists and Wall Street, which are — quite intentionally — never listed as being socially beneficial, because they tend to be parasitic and socially corrosive. It’s a shell game. Attention is drawn to dead ends and pipe dreams while the real and often repugnant drivers of the widespread adoption of these technologies drift into the shadows, away from public view and scrutiny. Taylor re-frames the question, away from that of the mainstream media and tech-boosters (often one and the same people), and toward the vetting process that lurks in the shadows. She instead asks the great question of the ancient Roman Consul Lucius Cassius: “Qui Bono?” (“to whose benefit?”). The answer to that question is usually a small minority, often morally repugnant violators of user privacy and owners of parasitic platforms hosting content by those whose labor is exploited. In many ways, Taylor’s analysis also mirrors that of Jeffrey Reiman‘s “Pyrrhic Defeat” theory in criminology: while a Pyrrhic Victory is a victory that comes at such a great cost that it amounts to a defeat, “Pyrrhic Defeat” is a nominal “defeat” of stated objectives in which those with power to alter the system benefit from the actually-existing conditions of “defeat” (something sort of related to the notion of “gaslighting”).

One key debate involves those who want the Internet to be a free-for-all, and those who want draconian control over it. While it is unsurprisingly a small but vocal minority that adopts the draconian approach, there are flaws in the other, free-for-all argument too. Taylor cites Elinor Ostrom, Peter Linebaugh, and other defenders of the commons against those who frequently take a right-Libertarian view of the Internet as a (market-based) “commons”, pointing out that, “In reality, differing circumstances, abilities, assets, and power render some better able to take advantage of a commons than others.” (Taylor doesn’t touch on it, but Michael Hudson has again written about “free trade” theory as causing economic polarization in much the same way). Taylor suggests that having a commons is socially-beneficial but to succeed requires regulation and enforcement of democratically-determined regulations. In other words, she once again sees the mainstream debate as being between the political right and the center-right, to the exclusion of a politically left position, which she adds to the debate.

Much like Aschoff, Taylor picks apart the fundamental insistence on neo-liberal capitalism embedded in “Web 2.0.” Drawing from the writings of Alice Marwick, she notes how online “self-branding” and relentless self-promotion is really about an insistence that neo-liberal political values be internalized. Any other views are marginalized. A similar argument was taken up by Miya Tokumitsu with her book Do What You Love, exploring how the injunction to do work that you love masks promotion of inequalities, victim-blaming, and anti-labor sentiment. Or for that matter, long before the Internet era, Erich Fromm theorized a “marketing” character orientation. This topic has also been the subject of some in-depth writing on the so-called “sharing economy” subsequent to Taylor’s book.

The book is written in a “journalistic” tone, but unlike most books of that sort that rely on dubious citations (if any) and anecdote without a coherent underlying theory, The People’s Platform is much, much more informed. Yes, some of the citations are still a bit light (many are digressions rather than clear support for her statements). Perhaps the biggest issue is Taylor’s injection of her subjective perspective as an independent documentary filmmaker into the book. This proves useful, in that it allows the reader to clearly identify her own point of view, given that every writer has one (some just refuse to admit it). Mostly Taylor’s own personal narrative provides examples to illustrate concepts she develops more generally. She does an especially good job conveying the nuance of the debate over intellectual property, and especially copyrights, noting how creative workers rely on it for income, while the “Web 2.0” companies use Internet software platforms to develop audiences that are sold to advertisers without any feeling of obligation to pay a living wage — or in many cases, anything at all — to content producers whose works are distributed on those platforms. Those who want everything to be free and open tend to be those who don’t depend on such compensation to survive.

And yet, Taylor does kind of overlook an old argument of the Standard Left Position. In the Nineteenth Century, the third best-selling book in the United States was Edward Bellamy‘s Looking Backward, a Rip Van Winkle tale about a man who goes into a trance in 1887 and wakes up in the year 2000 to find an essentially socialist utopia. What is interesting is that in that fictional socialist utopia Bellamy suggests that novelists are not compensated. They raise their own funds to publish — though there is a job guarantee so every citizen has a right to other gainful employment in a socially useful occupation. The key difference is that Taylor assumes (without explicitly discussing it in her book) that it is socially desirable to have “professional” creators of cultural/creative works. Bellamy suggested that an ideal society should not have such full-time content creators, but instead such things should all be done on an amateur basis, albeit in a society that provides ample leisure time and guaranteed income to enable substantial self-directed work to be performed. The idea there was later echoed in W.E.B. Du Bois‘ famous assertion that all art is propaganda, as well as in the work of various Frankfurt School scholars. This is a small loose end, though, in an otherwise thorough treatment of the topic.

In terms of the suggestions for the future, Taylor (implicitly at least) draws form the likes of Richard Wolff in suggesting cooperatives online, Robert McChesney in suggesting that media delivery companies should be taxed at full market value to eliminate the advantages that their natural monopoly or quasi public utility positions give them (e.g., for exclusive broadcasting licenses), and that content producers should be directly subsidized by the government. While many books like this that critique and criticize the existing state of affairs tend to fall down by making a bunch of absurd and/or unrealistic policy recommendations, Taylor is thankfully brief and vague about specifics, but offers a multitude of general suggestions that point toward improvements that could be pursued individually or all together. They aren’t really new suggestions but they are meaningful alternatives. She does, however, stop short of suggesting that neo-liberalism or capitalism as a whole be jettisoned, even though that is implicitly (and obviously) where her arguments point.

The Senior Dagar Brothers – Bihag Kamboji Malkosh

The Senior Dagar Brothers – Bihag Kamboji Malkosh: Calcutta 1955 Raga Records RAGA-221AB (2000)

This release is flawed only in the manner of its recording. As a live release, and an old one at that, there are some background noises audible and one of the brothers coughs repeatedly during the performance. “Raga Malkosh” is only heard for the first 25 minutes, and apparently the rest of the performance was not recorded. Fortunately, those things are only occasional annoyances and shouldn’t keep anyone away from this music. The performance itself is fantastic. I can’t tell the two brothers (Aminuddin Khan Dagar and Moinuddin Khan Dagar) apart on this record, but I’ve heard people comment that they trade off vocals in different pitch ranges so as to extend their collective range. These are morning ragas, so for best effect they should be heard in the morning. Fans of this should be sure to check out Pandit Pran Nath too.

Jeffrey St. Clair – Bully on the Bench

Link to an article by Jeffrey St. Clair:

The Panama Papers

Link to The Panama Papers

Bonus Links: “The Panama Papers Problem,” “Explaining the Panama Papers, or, Why Does a Dog Lick Himself?,” “Laundering Havens for War Budgets,” “The Corruption Revealed in the Panama Papers Opened the Door to Isis,” and “Iceland Names New Prime Minister in Wake of Panama Papers”

Kristine Mattis – The Cult of the Professional Class

Link to an article by Kristine Mattis:

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds – Live Seeds

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds – Live Seeds Mute CDSTUMM122 (1993)

Live Seeds, like most offerings from Nick Cave’s middle period, is an uneven affair. “Ship Song”, “Papa Won’t Leave You, Henry”, “From Her to Eternity” and “New Morning” are all fantastic, but elsewhere Cave and company lean far too heavily on his songwriting to do all the heavy lifting. In a way, that saps all the energy out of the songs. Maybe it’s a common trick artists use to regroup during a live set. But that doesn’t help the album at all.

In short, Live Seeds is an improvement over some of Cave’s previous few studio albums, but it pales in comparison to his earliest solo albums and the best material he produced about a decade later.

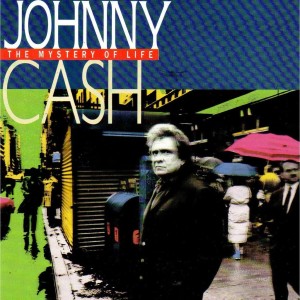

Johnny Cash – The Mystery of Life

Johnny Cash – The Mystery of Life Mercury 848 051-2 (1991)

By the early 1990s, it seemed like the world had given up on Johnny Cash. Well, at least his record labels had all given up on him. In an autobiography, he later claimed Mercury pressed only 500 copies of The Mystery of Life (Cash mistakenly called it The Meaning of Life), though it did scrape the bottom of the country charts. That’s a shame, because Cash was clearly interested in recording. His vocals sound clear and impassioned in a way that was totally lacking on most of his recordings from the late 1970s through just about all of the 1980s. If Water From the Wells of Home was supposed to be his comeback, then it says something that this album is a step up. It’s no winner. It’s still a rather middling affair. Producer “Cowboy” Jack Clement burdens this with heavy-handed production values that make all the instruments sound synthetic and artificial. But on top of Cash’s strong vocals, the band plays well enough (if you can look past the way they are recorded). Although the standard narrative is that Cash’s career was on the skids for decades before Rick Rubin revived it with American Recordings, this album is worth a look for fans to see that Cash was still in good form as a singer, but was always held back by everything else dumped into his records and a lack of promotion. That is to say Rick Rubin didn’t change much when he came along, he just recorded Cash without the other clutter and otherwise let Cash himself do basically exactly what he was doing here — particularly for Unchained — and actually promoted him. This one’s an interesting curio for those who’ve already heard Cash’s more acclaimed efforts and want to go back and fill-in some of the gaps to round out the picture.