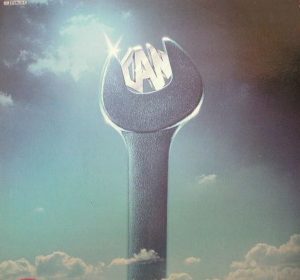

CAN – CAN Harvest 1C 066-45 099 (1978)

This is the last album that CAN recorded before disbanding (though they later reunited). The conventional narrative is that the band went downhill from 1974 onward. Is that fair? Yes and no. While the post-’74 material is by no means as pathbreaking, there is still much to like about it. The self-titled CAN (renamed Inner Space for some reissues) grapples with popular music of the day, which is to say disco, funk rock, even reggae, jazz fusion, and more. This ranges all over the place. Some of it (“A Spectacle”) even locks into a proto-hip-hop breakbeat-style groove. “E.F.S. Nr. 99 (‘Can Can’),” a rendition of Jacques Offenbach‘s iconic “Infernal Galop” composition, is sometimes greeted with a sneer, but it’s actually great! CAN had a sense of humor, which was one of their admirable qualities when it shone through, and this particularly sunny song is much less pretentious than a lot of other CAN genre tributes of the prior few years. Of course, the opener “All Gates Open” is really a song that ranks among the band’s best, with a moderate tempo, a mechanical rhythm with hints of ambient music, and a jammy, laid-back mystical quality evoked by the lyrics. “Safe” and “Sodom” are other particularly good ones. “Sunday Jam” is a dud, with cheesy smooth jazz trappings, but it proves to be the only dud on an otherwise fine album.

Don’t let the haters sour you on this, which is a good one for anyone with open ears (that is to say anyone who doesn’t limit CAN to their sound of the 1968-74 period). This has much more of a sense of purpose than the last couple CAN albums, which had good songs here and there but tended to kind of drift about aimlessly. It is sleeker, more immediate and more accessible than earlier CAN recordings, but it is no worse off for any of those qualities.