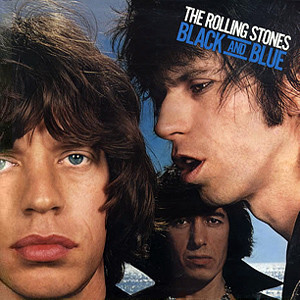

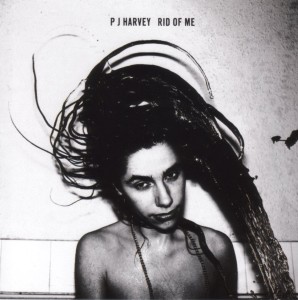

PJ Harvey – Rid of Me Island CID 8002 / 514 696-2 (1993)

The “grunge” rock movement was all about raw, loud, provocative sounds. When PJ Harvey released Rid of Me, as the style peaked in popularity, she recognized that dramatic effects could draw out the force of loud, distorted power chords by contrasting them against other things. This was her most aggressive sounding album. Yet the opener, the title track, begins with whispered vocals, muted guitar chords, and barely audible percussion before unleashing her distorted guitar and cry of “Don’t you don’t you wish you never never met her?,” first in a short burst, then completely unrestrained, like great beasts that struggle against their bridles and finally let themselves loose.

“50 Ft. Queenie” and “Me-Jane” are just knockout punches. These were different sorts of empowerment anthems. “50 Ft. Queenie” positions the protagonist as “king of the world” and rather than being some kind of dream, this is the sort of song that is going to make her (yes, her) the androgynous king of the world through raw power. This song roars. At the same time it mocks the male libidinal quest for dominance, while also entertaining the idea of a countercultural revolution to seize control in the name of a new order. It undermines the patriarchal claims to power by making the crude assertions of male sexuality like “I’m 20 inches long” in a way — shouted out by a woman — that robs them of their authenticity. “Me-Jane” is another one of those songs that Harvey does so well. It takes the Edgar Rice Burroughs Tarzan and Jane Porter characters, and converts Jane from a “damsel in distress” to the wise and thinking one suffering through Tarzan’s interminable chest-pounding and pointless screaming. PJ sings almost like she’s screaming too. But it’s the aural equivalent of rolling her eyes in contempt.

Provocative producer/recording engineer Steve Albini is on board. He gives this album a charismatic sound. Some love it; others hate it. The drums are indistinct, but loud, very loud. They present a low, pummeling rumble, like a photograph carefully kept just barely out of focus even in the central field of view. They sound like someone pounding away on something, the most literalist approach to what the drums are all about! The guitar, and PJ’s vocals are also given the same treatment. The bass is similarly indistinct, but without any of the loudness — what is normally the source of driving power in a lot of punk rock is here inverted, or, subverted, just like the gender roles addressed by the lyrics of numerous songs. “Rub ‘Til It Bleeds,” one of the heaviest songs on the first half of the album, exemplifies how the bass mostly provides noisy texture, rather than a rhythmic heartbeat. All together, this approach puts a number of the band’s individual elements or sounds on a more equal footing than is usually permitted. There is little room for any individual to assume the spotlight. Not even PJ’s vocals or guitar get special, preferential treatment. This is the hard rock equivalent of the sort of anarchistic “harmolodics” found on Ornette Coleman’s 1970s and 80s albums like Science Fiction and Of Human Feelings. For those who hated Albini’s production, demos of many of the songs were later released (4-Track Demos).

While PJ may have instinctively used a more bluesy foundation than what lay in Albini’s radical punk inclinations, the end results on Rid of Me perfectly encapsulate a sense of confrontation. It seems to perfectly fit the songwriting. None of the instruments get to assume their socially predestined roles. What helps separate this album from the ignorant clamor of something that just goes out as fast and loud as possible right from the start is not just that the clamor is juxtaposed with moments that regroup and coil up to await a springing attack, which it does magnificently, but also that the clamor and attack is a mass of seeming contradictions in and of itself. The drums, the guitar, the vocals have incongruous sonorities. And yet, they still come together to make a powerful statement inseparably bound up in a singular if slightly murky sonic fabric. This is close to the best of what “grunge” rock had to offer. It was a burst of something that cut against the grain. It was arresting. But it did that with an awareness of the past, and sense of its place in a line of failed attempts and counterrevolutions. This is why a cover of Dylan‘s “Highway 61 Revisited” makes sense here, as a link to the countercultural tradition of the 1960s, even if the performance doesn’t live up to the standards of the rest of the album.

Rid of Me had a leg up on much of the other “grunge” rock because its sense of purpose was fundamentally more dangerous. It was a sledgehammer. But it was a sledgehammer flying about in the midst of bystanders put suddenly on edge. While hindsight has shown that “grunge”, and any other movements in the same direction, failed to reach a tipping point to sustain their objectives, as the support for touring and mass media airplay were withdrawn after a few years, even decades later this music sounds as fresh and empowering as the day it was released.