![Gilberto Gil [Frevo rasgado]](data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20viewBox='0%200%20297%20300'%3E%3C/svg%3E)

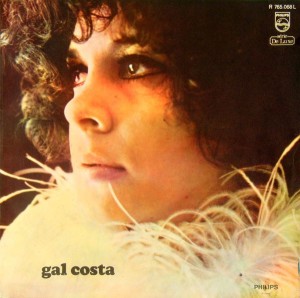

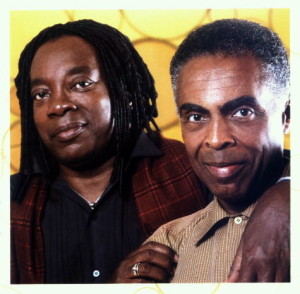

Gilberto Gil – Gilberto Gil [Frevo rasgado] Philips R 765.024 L (1968)

Of the albums to emerge from the tropicália movement, Gilberto Gil’s first self-titled album (sometimes referred to by the first song “Frevo rasgado” to distinguish it from his other self-titled albums) is one of the most playfully upbeat. It is also one more clearly indebted to The Beatles (Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Magical Mystery Tour) than most. Of course, arranger Rogério Duprat is on board and he deftly brings together all the disparate elements, from anachronistic afoxé/baião/folk musics of Bahia (Gil’s home state in northeastern Brazil) and cultured bossa nova to stately horns and refined strings to edgy psychedelic rock, gritty jovem guarda and energetic iê-iê-iê (Brazilian rock ‘n’ roll forms), in a way that totally sublimates the jarring discontinuities — epitomized on the iconic pastiche “Marginália II” (which goes as far as to quote military march music akin to “Marines’ Hymn”). There are jumps between styles within songs, and also across the many songs on the album. The rude and groovy psychedelic guitar riffs and rumbling samba drum beats of “Procissão” give way to “Luzia Luluza,” a delicately intricate baroque pop ballad with interspersed field recording/found sounds, lush and melancholic string arrangements, and alternately bright and fluttering wind instruments. The sheer breadth of this music is staggering. Yet it doesn’t exactly beat the listener down with heavy-handed pretensions. Much of this has a goofy irreverence that undercuts what might otherwise be dour seriousness with music this ambitious.

Christopher Dunn‘s excellent book Brutality Garden: Tropicália and the Emergence of a Brazilian Counterculture (2001), citing Lídia Santos, describes the tropicália movement’s satirical use of kitsch:

“One of the central aesthetic operations of Tropicália was the irreverent citation and celebration of all that was cafona (denoting ‘bad taste’) or kitsch in Brazilian culture. The kitsch object bears the mark of a temporal disjuncture, often appearing as anachronistic, inauthentic, or crudely imitative. The tropicalists’ calculated use of kitsch material was highly ambiguous and multivalent. First, it served to contest the prevailing standards of ‘good taste’ and seriousness of mid-1960s MPB. In this sense, it was a gesture of aesthetic populism because it acknowledged that the general public consumed and found meaning in cultural products that many critics dismissed as dated, stereotypical, and even alienated. Second, the tropicalists incorporated kitsch material as a way to satirize the retrograde social and political values that returned with military rule.” (p. 124).

Dunn further stresses “the ambiguities of tropicalist song, in which the line between sincerity and sarcasm, complicity and critique, was often blurred.” (p. 153). He also refers to some of these same techniques as illustrative of the use of allegory. (p. 86). He traces the roots of the musical movement to things like the 1928 “Manifesto Antropófago [Cannibalist Manifesto]” of Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade and French playwright/actor Antonin Artaud‘s Theater of Cruelty. (pp. 17, 78). There are many latter-day analogues, such as Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti. But there is a question of whether “cynicism” is the right term here. Ariel Pink’s music might be described as using what Peter Sloterdijk calls “kynicism” (or classical cynicism), which has been summarized as: exposing the self-interested egotism and claims to power behind official discourse by holding it up to banal ridicule. Miloš Forman‘s early films made behind the Iron Curtain did this too.

The tropicalists did all this within a somewhat specific context of the Third World Project and Non-aligned Movement (for that history, see Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (2007)) and colonial liberation movements in the spirit of Frantz Fanon et al. Those efforts were all about casting off the yoke of colonialism with both a materially independent (yet not isolationist) economic system and a psychological break from a colonized mindset. This was a musical project with similar aims.

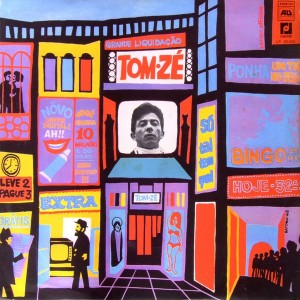

My pal Toni encapsulated the heart of the matter in a review of Tom Zé‘s debut album:

“So what makes tropicalismo so unique? Is it the Bahia folk influence, the focus on emotional expression rather than rock ‘n roll grooves? Those too, but I think the most important difference is the songwriting & the arrangements. Brazilian songwriters never seem ashamed to use extravagant horn & string sections on their albums, or restrain from including folk & tribal parts in the songs. Avantgarde, African & ‘alternative’ music all melt together to form multi-dimensional music that you can’t pigeonhole, which is I guess why mostly nondescript names such as tropicalismo and ‘musica popular brasileira’ get thrown around.”

The tropicalists adopt all sorts of things, without guilt about doing it. This is what made them so radical.

Dunn’s book puzzles over the censorship and arrests of Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso, claiming that such government action was “arbitrary and misinformed” (p. 147) in view of the more obvious protest music that was not treated as harshly. But, I think, this is a wrongheaded approach. Caetano Veloso, in his memoir Tropical Truth, takes a contrary position when he recounts an episode as he and Gil were about to be released from imprisonment by the military, about being called to the office of a captain who had underwent special anti-guerrilla training in the United States, “He said he understood clearly that what Gil and I were doing was much more dangerous than the work of artists who were engaged in explicit protests and political activity.” Dunn overlooks a possibility here, one that is explained by Slavoj Žižek, whose In Defense of Lost Causes (2008) discusses the curious difference between composers Sergei Prokofiev [Сергей Сергеевич Прокофьев] and Dmitri Shostakovitch [Дми́трий Дми́триевич Шостако́вич] in the Soviet Union:

“what if what makes Shostakovich’s music ‘Stalinist,’ a part of the Soviet universe, is his very distance towards it? What if distance towards the official ideological universe, far from undermining it, was a key constituent of its functioning? *** If there is a lesson to be learned from the functioning of Stalinist ideology, it is that (public) appearances matter, which is why one should reserve the category ‘dissidence’ exclusively for the public discourse: ‘dissidents’ were only those who disturbed the smooth functioning of the public discourse, announcing publicly — in one way or another — what, privately, everybody already knew. *** What if the Stalinist rejection of both Prokofiev’s propagandistic and intimate works was right on its own terms? What if they wanted from him was precisely the coexistence of two levels, propagandistic and intimate, while he was offering them either the first or the second? *** Nonetheless, the subjective position of Prokofiev is here radically different from that of Shostakovich: one can propose the thesis that, in contrast to Shostakovich, Prokofiev was effectively not a ‘Soviet composer,’ even if he wrote more than Shotakovich’s share of official cantatas celebrating Stalin and his regime. Prokofiev adopted a kind of proto-psychotic position of internal exclusion towards Stalinism: he was not internally affected or bothered by it, that is, he treated it as just an external nuisance. There was effectively something childish in Prokofiev, like the refusal of a spoilt child to accept one’s place in the social order of things . . . . What if . . . Shostakovich’s popularity is the sign of a non-event, a moment of the vast cultural counter-revolution whose political mark is the withdrawal from radical emancipatory politics, and the refocusing on human rights and the prevention of suffering?” (pp. 236-246).

The parallels aren’t exact here, but Gilberto Gil’s music on his first self-titled album — like much other music of tropicália — puts an emancipatory agenda on the table by drawing no high/low cultural distinctions between music of the poor in Brazil, officially sanctioned music, and popular music of the core economies of the global West. He simply refuses to internally accept any boundaries of that sort. Yet the Brazilian junta depended upon a distinction between core and peripheral economies. As the Brazilian political economist Ruy Mauro Marini noted just a few years before Gil’s album was released, the Brazilian military state engaged in a kind of collaborationist “sub-imperialism” that involved collaborating actively with (core economy) imperialist expansion, assuming in that expansion the position of a key nation. RM Marini, “Brazilian Interdependence and Imperialist Integration,” Monthly Review, Vol. 17, No. 7, p. 22 (Dec. 1965). Gil’s music may present a “public” discourse that is ambiguously involved with parts of the traditions of Brazil and its colonial past, but its “internal” stance stands apart from the ideology that sustained the authoritarian, conservative, “sub-imperialist” junta. So, contrary to Dunn (though later in his book he briefly acknowledges a view of Gil’s “symbolic” interventions), I think the censors in Brazil were actually quite astute in their persecutions of Gil and Veloso, who presented a much deeper problem for the military regime than did the protest signers of the time, who like “beautiful souls” accepted an outsider position that paradoxically helped sustain the regime.

Of course, the tropicalist movement evaporated in only a matter of years, as Gil and Veloso were jailed and then exiled. Gil in particular is often accused of giving up on the emancipatory project after his return from exile in favor of a tepid acceptance of the center-liberal “refocusing on human rights and the prevention of suffering” and wholesale adoption of typical “Western” (core economy) musical values. But, none of that had happened yet with Gilberto Gil, and that album still sounds daring nearly a half-century later.

![Gilberto Gil [Frevo rasgado]](http://rocksalted.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/gilbertogil1-297x300.jpg)