Link to a transcript:

The Red Krayola – God Bless the Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It

The Red Krayola – God Bless the Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It International Artists IA LP 7 (1968)

Of all the inventive rock music of the tail end of the 1960s, God Bless the Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It has the distinction of being one that still sounds revolutionary almost 50 years later. The songs (some can barely be called “songs” as such) mock contemporary rock and pop trends. Sometimes typical 1960s vocal pop choruses are presented, but a cappella (“Music,” “Sherlock Holmes”). The drums occasionally react to the other instruments rather than provide a propulsive, syncopated beat (“Say Hello to Jamie Jones”). Other songs are self-consciously disorganized, with the musicians playing at different tempos, completely out of sync (“Save the House,” “Sheriff Jack,” “The Jewels of the Madonna”). “Listen to This” consists of the spoken announcement, “Listen to this,” followed by a staccato plunking of a single key on the piano, totaling all of eight seconds. The shameless insolence of Diogenes does come to mind. There are some vaguely catchy, if abstract and angular, riffs and melodies here and there (“Dairarymaid’s Lament,” “Leejol,” “Dirth of Tilth,” “Tina’s Gone to Have a Baby”). They end up being yet another unpredictable facet of the album, confounding expectations that can’t even categorically deny “conventional” rock. None of the varied, strange devices dominates the album. While that factor might explain while opinions are mixed, and why this has never really been assimilated into mainstream rock aside from a few punk and post-rock outfits, it also suggests why the movement of the late 1960s counterculture as a whole failed, because stuff like this never caught on. People tended to cling to the stuff that was more salable, collapsing the movement back into those discrete aspects that fit best within the pre-existing paradigm. But God Bless the Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It didn’t fit that paradigm. It still is a remarkably fresh and inventive album. While the power centers of society may have pushed back against the 1960s counterculture, trying to prove that consumerism and nuclear families are the only viable options, The Red Krayola left behind artifacts like this, a surviving rebuttal that couldn’t quite be absorbed and co-opted. Texan acts like labelmates The 13th Floor Elevators, but also the likes of Jandek and Ornette Coleman, seemed to have a way of not just taking chances, but trying to casually either make the Earth move or take leave of it entirely. They reframed the concept of what a safe and secure life meant, placing within a collaborative dialog the possibility of chance, variation, and individuality. But few were as irreverently funny as The Red Krayola.

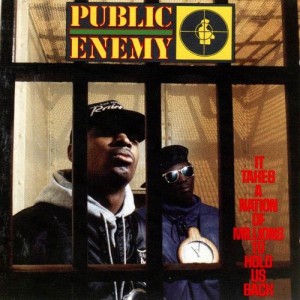

Public Enemy – It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back

Public Enemy – It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back Def Jam BFW 44303 (1988)

No one could have expected It Takes A Nation of Millions. It was too much of an album to expect. Chuck D packs thought provoking messages into a bomb he detonates before you. It Takes A Nation of Millions wakes listeners to a whole new level of consciousness.

Flavor Flav was out there. Complete with clock (though Chuck D still wore one too), he was the wild card that made Public Enemy work. His crazy rhymes kept coming. He injected a different sense of rhythm into the whole. It was an attack from many sides as long as Flavor Flav was there.

Terminator X, Professor Griff and the others tend to be forgotten, as they aren’t even on the album cover. They were critical. Terminator X’s (and Johnny Juice‘s) aggressive scratches and the hard beats of The Bomb Squad were relentless. Looping again and again, the most powerful elements were isolated. The push was overpowering. Public Enemy had a sound that might have been a lot of things, but it certainly could not be ignored. It Takes A Nation of Millions dominates as long as it is playing.

The density of what is on a Public Enemy record had roots, but this was a new kind of concentration. Miles Davis’ On the Corner provided the layered street funk attitude. The harsh beats and fondness for raw noise resembled industrial music too (for instance, Mark Stewart‘s As the Veneer of Democracy Starts to Fade, Ministry). As Michael Denning wrote in Noise Uprising about early sound recordings just before the Great Depression, “If noise is unwanted sound, interference, sound out of place, it is also a powerful human weapon, a violent breaking of the sonic order. *** In this frame, these musics represented the refusal of deference, the assertion of noise for noise’s sake, the singing of the subaltern . . . .” This revolutionary attitude also — even if by chance — echoed punks like The Pop Group. Public Enemy sorted through every possibility to direct their efforts. They created chaos as needed, and could cut through it at will. Chuck D and his crew had control. That was the difference. They weren’t held back by the ordinary expectations of continuing to build on the past. It was more about striking out in the proper direction. Working with exactly the same sounds other musicians used, Public Enemy used them as ammunition to make sure their path was clear.

There is definitely a surplus of ideas here. There is more in a single song here than in many artists’ whole careers. Public Enemy works very hard to put so much across in every song. It helped, perhaps, that the band was so large. There were many talents to draw on.

It is also obligatory to mention that this was a record made before the advent of sample clearing. So no one makes them this way anymore. Not that anyone really did at the time either. When jazz pianist Cecil Taylor got started he did something unique, but it wasn’t long before he ratcheted up the speed and complexity by a factor of ten. It is like that here. Run-D.M.C. and the early hip-hop pioneers were no doubt influences and precedents, but It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back took all that and delivered it at hyperspeed. If that weren’t enough, all the samples come at the listener in a barrage of noise, squawking repetition and booming thuds. The samples draw on history, allusion and implied meaning, but also refuse to simply restate existing meaning, instead insisting on imposing further meaning. Put another way, PE and the Bomb Squad didn’t just appropriate the proven appeal of the material they sampled, but took that as merely a starting point, a contextual reference point, to fashion something of their own that had significance beyond that of the sample.

The band uses the samples in a way that really creates a platform for the political messages. Although the harshness and aggression of the beats seems like a way to frighten listeners, it was also a way to draw in the willing. Like heavy metal? Well, PE threw out some metal samples, but just shards and slivers, enough to make a listener who is into it find some common ground, but only enough to catch her attention and propose a deeper connection. It is the same for the vintage soul and funk samples. They provided some basis for their stance too. There is rapping about not believing the hype, but they also include a snippet of a radio DJ calling them “suckers”. And when building momentum, they play a live recording from a London show. This wasn’t just a bunch of conclusory opinions. This is an album that makes the effort to provide some evidence to contextualize its stances. But what really made this band — and this album in particular — so special was that they built everything from very elemental concepts. Chuck D and the Bomb Squad didn’t just present political programs, they built them up from more fundamental positions. They get into deeper, abstract philosophical questions, and their political stance unfolds from them.

Public Enemy was self-aware of their own controversial status in the music industry. This comes to a head on songs like “Don’t Believe the Hype.” They engage this controversy, without defining themselves entirely by it or dismissing it outright. They don’t get caught up in merely self-referential excess either.

One of the great albums of its day, or any, It Takes A Nation of Millions raised the bar. Public Enemy were an exceedingly intelligent group. It was the minds behind the music that made the album. They still focused all their attention on being levelheaded champions of their people. Fuck the finer points, it’s just good to listen to.

Barbara and Karen Fields – How Race is Conjured

Link to an interview with Barbara and Karen Fields by Jason Farbman:

Very interesting comments on “racecraft”. Though the comparisons to non-causality are a little tenuous in the interview, and the gap between psychology and sociology is not so big if one compares, say, Lacan and Bourdieu. Still, the distinction between identity and identification seems crucial.

Otis Redding – Otis Blue/Otis Redding Sings Soul

Otis Redding – Otis Blue/Otis Redding Sings Soul Volt S-412 (1965)

“When you can do the common things of life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.” – George Washington Carver

Otis Redding sang songs about the common things of life. He called up many sorts of feelings, but he always sang in response to common things and shared human experiences. What set Otis apart was his deep sympathy for all the good there could be in the world. His stuff, even with hard-times blues feelings, had positive emotion behind it. The context was familiar but Otis’ soul feeling had a romantic precision — quite the same exceptional insight found in the portraits Vermeer painted. He always located an incorruptible goodness at the foundation of every one of his songs.

Only three originals make the album, but they are each classics. “Ole Man Trouble” has the plodding organ of Booker T. Jones in the background with Steve Cropper’s guitar lacing its way around the melody. Aretha may have later taken “Respect” for her own, but Otis still belted out the original nicely.

Otis really grew out of the frenetic Little Richard school of R&B, but was a also great admirer of the smooth crooning of Sam Cooke. Here Otis unleashes three songs from his Cooke repertoire. “Change Gonna Come” has a muggy intimacy that swells around every aching hope. Al Jackson, Jr.’s drums add heart to the song’s soul. It’s a rendition that would have made Cooke proud.

The other covers Otis includes make sure the album is solid throughout. “My Girl” is a tough song to pull off with less than five Temptations, but Otis was up to the challenge. The Stones’ “Satisfaction” is a song practically written for Otis to sing. This gritty, driving take is one of the best on wax. Otis sings in a fervor that perfectly compliments the rumble from “Duck” Dunn’s bass. Solomon Burke’s “Down In the Valley” has The Memphis Horns dishing their whimsical best through some taught harmonies.

Southern soul out of Stax records in Memphis (Volt was a Stax imprint) had the do-it-yourself charm of letting the performers’ personalities come through. The point was to reach for what mattered. Few, if any, other soul singers could reach as deep as Otis. He knew how to pull out an exasperated cry whenever needed. Otis had instincts that can’t be taught. Being from an uncommon kind of talent, his singing on records like Otis Blue/Otis Redding Sings Soul still commands attention.

Evelyn McDonnell Interviews Richard Goldstein

Link to an interview of Richard Goldstein by Evelyn McDonnell about the book Another Little Piece of My Heart: My Life of Rock and Revolution in the ’60s (2015):

“Live Through This: A Pioneering Rock Critic Looks Back with Love and Sorrow on the 1960s”

John Quiggin – John Locke Against Freedom

Link to an article by John Quiggin:

Glen Campbell – Rhinestone Cowboy

Glen Campbell – Rhinestone Cowboy Capitol SW-11430 (1975)

In the same territory as The Carpenters, or maybe even Neil Diamond, Glen Campbell’s Rhinestone Cowboy has that inimitable 1960s/70s pop country easy listening thing going in full effect, complete with songs that tend to portray a sort of weary, dejected dark side of the “good life”. Things like “Country Boy (You Got Your Feet in L.A.)” and “Marie” go to places that Harry Nilsson went (ever notice that Nilsson’s hit 1968 version of Fred Neil‘s “Everybody’s Talkin'” is basically a superior re-make of Campbell’s “Gentle on My Mind” from 1967?), but with a little more straightforward professional reticence. What differs from some of Campbell’s earlier hits is that this is a little more bombastic and self-consciously grandiose in the backing arrangements. And that suits him perfectly. His voice, of course, is a dream. He may not be Karen Carpenter, but damn! It is kind of interesting, too, that he performs “My Girl,” almost like the flip side of Al Green recording Hank Williams, Willie Nelson and Roy Orbison songs. It is emblematic of how most of this album focuses on themes of coping with being thrust into new geographies, being faced with new burdens, and the like, and on trying to humbly overcome those challenges with hard work and effort, but maybe not being able to comprehend if that will work or how else to go about facing those challenges. Some people dismiss this as pure camp or kitsch, but really, a closer listen suggests that those might be coping mechanisms. And even more interesting, perhaps, is how this music sits right on the line between “material” concerns like having a job, providing for a family, etc. and “personal” concerns like heartbreak, anxiety, and other more existential topics.

Sonic Youth – Rather Ripped

Sonic Youth – Rather Ripped Geffen B0006757-02 (2006)

A rather average album. It’s only slightly better than Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star, which isn’t saying much. The Youth seem disinterested here. It all sounds like a concerted effort to sound “straight”, or at least “marketable”, by reigning in the songs to shorter lengths and having more well-defined beginning/middle/end song structures. But it all is too forced and self-referential. The first two tracks are nice though.

The intriguing but often unsatisfying thing about Sonic Youth was that they evolved over their long existence, at a pace that is frustrating in hindsight. So many of their albums kept one foot in whatever style they had recently found success with while tentatively stepping into all sorts of other areas. This had the effect of feeling like they clung to what they had done before out of force of habit — or maybe for commercial reasons? — while taking their sweet time to sort out their next move. Their peaks, of which they had many, tended to appear on record when they locked into a particular style and stuck with it. So, their debut, then EVOL–Sister–Daydream Nation, then *maybe* Dirty, and then Murray Street, all of those locked into something more specific. Some of the transitional material is good, but also doggedly varied in a way that prompts a listener looking back to say, “Ah, but they did that part better on the next album.” Yet, on the other hand, Sonic Youth were always trying new things, and so there always were new parts to consider. At least, there were new parts until Rather Ripped, which along with The Eternal had them stagnating if not looking backward for the first time in their career.

Did I mention that I miss Jim O’Rourke already? If not, I am now. This was the band’s first album without him after his brief tenure in the band, and his creativity and good humor seems conspicuously absent.

Matthew Shipp – Matthew Shipp’s New Orbit

Matthew Shipp – Matthew Shipp’s New Orbit Thirsty Ear HI57095.2 (2001)

Matthew Shipp’s New Orbit expands on his pivotal Pastoral Composure album. Even after seventeen albums, Shipp has seemingly just scratched the surface.

Most interestingly, this recording explores new approaches to mixing and recording a jazz album, drawing heavily from the realm of contemporary (independent) rock. Though rooted in tradition, the quartet freely reinterprets existing technique to unfold fresh new arrangements. Shipp’s style is the new thing: continually propelled rhythms on the piano; flowing melodic elements that obscure any and all boundaries of form; and spatial rather than computational conception. There is ample time for solos. Everyone takes the opportunity for extended, unaccompanied passages. The individual flavors then blend seamlessly back into the group dynamic. Often the effect is a droning meditation. Natural elements are set against celestial backdrops. The result is a cohesive sound. While abstract, the structures are purposeful and drive towards a fuzzy destination in the distance.

Wadada Leo Smith on trumpet is a perfect fit with the group. Long-time associate William Parker delivers a stellar performance on bass, as expected. The dynamic duo of Shipp/Parker is the modern equivalent of Harris/McCann, Armstrong/Hines, Ellington/Blanton, or Montgomery/Smith. Parker balances pizzicato (plucked strings) and arco (with a bow) to make full use of his talents. The bass has a natural sound, but one constantly pushed towards expressive limits. Drummer Gerald Cleaver turns in one of his finest performances to date. The group has reached unseen heights of individual and collective performance.

Scientific song titles suggest a high technology milieu — implying that jazz has not commented sufficiently on technology in the past. Each track elicits a new response. “Chi” is guided by rhythms. “New Orbit” is pensive and reflective. “Paradox X” is mysterious, with dissonances filling huge amounts of space. William Parker shines on “Orbit 3.” Gerald Cleaver pulls “U Feature” together by dropping in abstract bass drum hits. Wadada Leo Smith sets off “Maze Hint” with an intense trumpet solo that retroactively changes the album to that point.

Matthew Shipp’s New Orbit is the state of music; Matthew Shipp and friends reaffirm their status as jazz innovators. Hunter S. Thompson has said Muhammad Ali may not have been perfect, but came as close as we are likely to see in this life. There is no more fitting a description for this group. They may be carbon-based life forms, but the crucible of this musical partnership has transformed this bunch of atoms to diamonds.