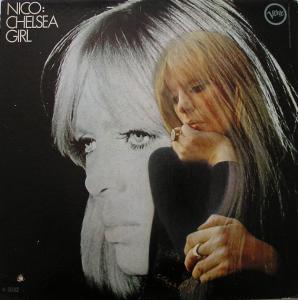

Nico – Chelsea Girl Elektra V6-5032 (1967)

Nico’s Chelsea Girl is an overlooked classic. While certainly a product of the 60s folk movement, this album stands apart from the gritty yet welcoming humanity of the usual folk-rock. It instead cascades through personal trials of someone out of step with the multitudes. The album focuses on the wonder and feeling of experiencing a time without answers. What makes it so unique is the album’s ability to fit within a much larger scheme. Chelsea Girl plays its part magnificently.

A model in Europe, Nico (born Christa Päffgen) managed to get a part in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960). In the U.S., she studied at the Actor’s Studio as a classmate of Marilyn Monroe. Nico also fell in with the Andy Warhol Factory crowd. As a Warhol “superstar” she appeared in movies like The Chelsea Girls (1966) and **** (1967). Warhol was eager to promote Nico’s singing career by pushing her into a role with The Velvet Underground. Nico provided another sonic texture to the Velvets, who changed music forever with their new urban musical experiments. The interpersonal dissonance she created in the group only permitted a short stay. The Velvets were not a backing band and Nico wanted to be a solo star–like Bob Dylan.

Chelsea Girl is a fantastic debut album, through the combined efforts of many. Nico sings “I’ll Keep It with Mine,” which Bob Dylan wrote for her (but first recorded by Judy Collins). Lou Reed, John Cale, and Sterling Morrison from the Velvet Underground provided five songs between them and perform on a number of the tracks. Jackson Browne wrote three songs. Browne also plays guitar on the album, having played behind Nico at live shows (alternating with other guitarists like Tim Buckley, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Tim Hardin). Renowned producer Tom Wilson pulls the far-reaching aspirations of Chelsea Girl together. The soft strings and flute arranged by Larry Fallon add just enough sweet beauty to the songs. Wilson precisely matches every sound against Nico’s voice. While Chelsea Girl‘s orchestral chamber folk tracks certain currents in the New York folk music scene at the time, there is an apolitical melancholy to it that other vaguely similar examples lack.

A voice takes this album to new places. Virgin ears, however, may take a moment to adjust. Nico sings with an icy drone that seems to pull all parts of the chromatic scale into just one tone. She is not only guileless, but she seems positively incapable of guile in her voice. Her English isn’t clean, almost like a low Germanic rumble. The music is isolated. Often tragic, the album echoes a lasting wisdom in its bleak messages. The deepest beauty of the music is its cerebral, existential intrigue. Yet, the calm arrangements make the album still accessible. Chelsea Girl has the same peaceful acceptance of a tragic world found in John Coltrane’s last recordings from about the same time.

The title song flows with a cool but sweet melody, narrating a insider’s look into Warhol’s “Chelsea Girls.” “I’ll Keep It with Mine” has the atmospheric pop qualities you expect from a Dylan song, but seems even prettier after the title track. “Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams” falls together perfectly as a metaphor for the entire album. It would never work without Nico’s emotional detachment though. The deep, unsentimental searching in her voice has never been duplicated. Perhaps the most noted songs on the album are “The Fairest of the Seasons” and “These Days.” You actually have to appreciate the rarity of such pure statements. She may not have a dazzling range, to put it mildly, but Nico had a powerful ability to make moving music.

Chelsea Girl in a way expands on her very first recordings made with Brian Jones, Jimmy Page, and Andrew Loog Oldham. This album did have a heavy influence by producer Tom Wilson and the rumor is that neither Nico nor the Velvet Underground crowd liked the results. She certainly never made music even remotely similar again. Her next few albums established Nico as a goth queen whose music bore more from 20th-century classical than any kind of rock and roll. Only “It Was a Pleasure Then” hints at her later work, and even then only slightly.

While Nico never went beyond underground status as a singer, the present time would have been kinder to her. She did influence plenty of alt-folk like Tim Buckley and Nick Drake. Never truly understood on its own terms, but the success of latter-day alt-folk artists and the inclusion of some of her songs on The Royal Tenenbaums soundtrack show the world eventually readied itself for the sound of Chelsea Girl. Personal problems and drug additions aside, a model like Nico could have gone far in the realm of music videos as well. She was closely involved with many of the greatest artists of the last century, and her legacy certainly belongs with them.