The Velvet Underground & Nico – The Velvet Underground & Nico Verve V6-5008 (1967)

It may be impossible to hold your breath for forty-eight minutes, but The Velvet Underground & Nico makes you want to try. The themes are so timeless success was inevitable if not immediate. Haunting is the wrong word to describe this album. Here was rock ‘n’ roll with an urban soul. This music had compassion–not in the sense of orphans and puppy dogs, but in terms of some bleak realities music had heretofore largely ignored. There is no single, definitive rock ‘n’ roll album that obviates all needs and desires. The Velvet Underground & Nico does provide an expansive view of all that is possible. It is a rare glimpse into something daring yet fully-formed. Congratulations Velvets, it worked.

The Velvet Underground were one of the most important rock ‘n’ roll groups in history. As rock music’s reclaimed gem, the band’s influence fundamentally shifted the direction modern music was taking. The Velvets precisely divide early and modern rock ‘n’ roll. When this album came out, less than “no one” cared. Yet, as Brian Eno is often quoted saying, everyone who bought this record started a band. Through the miracle of historical revision, the music world corrected its oversight and has now placed the Velvet Underground at the peak of rock history where they belong. A record collection without the Velvet Underground & Nico is laughable.

The band was incredibly talented. John Cale and Lou Reed were the highly visible creative centers, but Sterling Morrison and Moe Tucker provided the heartbeats of the band. Moe Tucker never played drum rolls, and was unafraid to use mallets. She could turn a Bo Diddley beat into a modern rock mainstay, as with “Run Run Run”. Morrison played subtle parts that perfectly framed the experimental pieces. The Velvet’s cavalier style threw together anything that produced a good sound. It is simply wrong to say they sounded unlike anything before them. There are elements of La Monte Young’s minimalism (including Eastern classical drones), energetic old-fashioned R & B, doo-wop harmonies (drawn from gospel), twangy country trimmings, controlled guitar feedback, rough layered blues, subdued rockabilly energy, folk-y personal reflection, and girl-group production values. The album deftly melded all these elements along with something more, as witnesses as “There She Goes Again” is more than a duplication of The Rolling Stones playing Marvin Gaye’s “Hitch Hike.” Their genius comes not from mere combinatory music, but developing an entirely new approach to music through which they combined many existing elements. The highly experimental sound comes largely thanks to John Cale. Lou Reed provided the timeless lyrics, exposing the seedy side of the city. Sex, drugs, & rock n’ roll are no long just implied in the music. The Velvets bluntly present these things, making them the first urban rock band and the true rock revolutionaries of the 1960s.

The songs are at times pretty and at times provocative. The group set out to change rock ‘n’ roll, and that is exactly what they did (even if few noticed at first). “Sunday Morning” (the one song produced by Tom Wilson) is tells of a lonely person wondering about a lifetime made of tarnished days and weeks. “Heroin” and “Waiting for My Man” are drug opuses on a grand scale, but they retain a strange objectivity. The singer does not seem to draw any conclusions, understanding only what he doesn’t know. “Heroin” is the grand realization in music of Arthur Rimbaud’s Les Illuminations. Lou Reed had an incredible talent for turning ordinary life into extraordinary stories. He also tells the stories through simple words. It is easy to speak with complicated words, all you have to do is grab a thesaurus and/or go to college. A far more difficult task is speaking to a variety of social circles in a way understandable to everyone. The results are spectacular and timeless. Reed’s onetime mentor and drinking buddy Delmore Schwartz would not have it any other way.

“Produced” by Andy Warhol, the group’s debut album was really their own effort. Andy Warhol essentially did everything he could for the band, because without him the Velvet Underground would not even be an obscurity in history. Warhol gave the band money to record this thing and promoted a traveling multimedia extravaganza he called “the Exploding Plastic Inevitable.” The Velvets cashed in on Warhol’s image; unfortunately, that wasn’t enough for the general public to digest them. Paul Morrissey (one of Warhol’s right-hand men) may have done some legwork, but it was Warhol who created and cultivated his own pop phenomenon. He also okayed the band to include all their “dirty words.” Warhol issuing his meek little approval wasn’t meaningless.

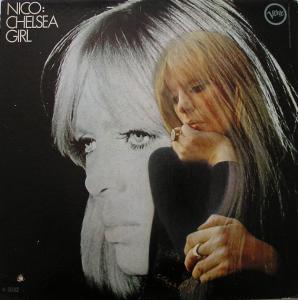

Warhol forced Nico into the band, so Reed and Cale reluctantly let her sing three songs for the album. In fact, she provided the perfect foil for the band. Her deadpan vocals were decidedly non-expressionist. The twist she provides to “Femme Fatale” made it a classic. “I’ll Be Your Mirror” is icily detached in a way that seems both proper and necessary. But it also is warm. In the documentary film Nico Icon, Nico’s aunt (who raised her) plays “I’ll Be Your Mirror” and kind of dances and sings along as best she can (though she only knew German). These songs mean something, to people of all kinds. Like the whole Warhol Factory, the music serves a whole segment of society previously cast from view and memory. The third song Nico sung, “All Tomorrow’s Parties” makes a near comic, near tragic description of the poor little rich girls all about the Warhol crowd. Nico’s detached performance is very much a savior of urban life in America. Or something like that. Like the new aesthetic of the Bauhaus school, she provides a new set of values to judge an increasingly mass-produced rock ‘n’ roll product. Nico was of course ahead of her time, but she was indispensable in the music she made with and without the Velvets. The Velvets (more specifically Reed & Cale) did not desire to be Nico’s backing band, nor did Nico want to be a part-time singer for a group that didn’t need her. They said she couldn’t sing in tune, yet the Velvets never tried to play “in tune” (making for some strange disagreements). The perfect solution was to splinter off Nico to pursue her own solo career (with John Cale playing a central role) keeping those three Nico vocals with the Velvets as nice little memories of something fleeting.

Funds were very thin in the recording process. Warhol didn’t float the Velvet much money. Many of the final album tracks were first takes, or had little editing. The ultimate tribute to the Velvets is their ability to produce one of the greatest recordings ever under such oppressive conditions. This album hardly represents the band’s potential. Consensus says the group was much better live. Only rock’s greatest band could have such a fantastic under-achievement as The Velvet Underground & Nico.

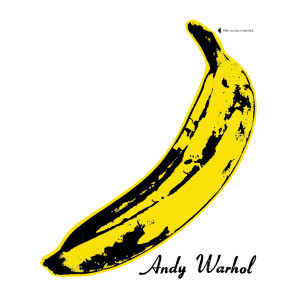

One of the benefits of having Andy Warhol as your “producer” is he can design your album cover. The Warhol banana is now synonymous with the Velvet Underground. The original album jacket had a peel-off peel that revealed a pink banana inside. The back of the album actually had a profound impact on the future of the band. An image shows the band at the Exploding Plastic Inevitable with a Warhol film projected onto them as they perform. It turned out that one of the people in the projected film (Eric Emerson) whose face appeared on the back of the album created legal hassles that delayed release. The Velvets had a tenuous hold on their captive audience to say the least. They fit perfectly with the Warhol crowd, but even the more open-minded segments of uptight American society were hardly ready for them. Despite rigorous live performance schedules, the timing of the album release hurt sales. Andy Warhol’s name and image could only do so much to push sales.

The argument over Eric Emerson’s image that delayed the album’s release cemented the commercial failure of this classic. It wasn’t that people didn’t like the Velvets. Originally their concerts were quite popular, and they had capacity crowds. The Mothers of Invention with Frank Zappa used to open for the Velvets. Zappa’s nasty personality surfaced though some bitter turf wars–the Mothers and Velvets were the first two rock groups signed to Verve records, and the Mothers took it upon themselves to use any means necessary to sell more records. Zappa concluded shows by saying how the headlining band sucked and that everyone should leave. This animosity always surprised the Velvets, but they were no angels (they literally threw shit around on tour). The devoutly believed they were the greatest rock ‘n’ roll band in the world. They were right, but no one believed them. Lou Reed would not hesitate to bad-mouth any group he considered crappy. But the Velvets did respect talent. They regularly attended James Brown shows, and hung out with The Rolling Stones. There was also a great deal of respect for The Beach Boys, who don’t always get credit as being one of the most innovative and creative groups of the late 1960s.

The “right” people heard the Velvet Underground: CAN, The Stooges, Jimi Hendrix, Sonny & Cher, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, New York Dolls, Television, Patti Smith, Roxy Music, The Fall, Sonic Youth, The Modern Lovers, The Voidoids (particularly Robert Quine), Rocket From the Tombs, and yes even The Doors (to name a few).

The Velvet Underground seem to paint a dark vision of the world. It still is one good enough to suggest limitless possibilities. They glorify the hopes and aspirations of fundamental aspects of urban life. Even on “The Black Angel’s Death Song” the Velvets’ music was free and uplifting, as Reed sings: “choose to choose.” They didn’t just hope and dream, but took action to make things better through their music. The Velvets’ intellectual and arty approach goes beyond some peoples’ patience or taste. This isn’t to say the Velvets are an elitist music, quite the contrary. The Velvet Underground completely identify with a section of society. Their broad, non-directional approach holds up better than lesser, narrow-minded music. Indifferent to a society that refused to accept them, their sound progressed. Anyone not satisfied accepting the world at wholesale face value will have a strong inclination to like the Velvets.

Actually, White Light/White Heat may (repeat: may) be the better album, but this one was first. This album dared into the unknown. The audacity to release this record is itself the very essence of rock ‘n’ roll.

The Velvet Underground weren’t just some band that made interesting music. They were heroes–and a heroine or two. It was against monumental odds that they created music. The Velvet Underground were, like Karlheinz Stockhausen would say, the esoteric fringe where the arts now live. It wasn’t just that they had a limited following, lots of people hated them! Without Andy Warhol, the Velvet would have had to pack it up after about five concerts for lack of anywhere to play or record. But that wasn’t what happened. The Velvets did it. They made this lasting document that ultimately did change the world.